On rubbing, it’s normal to detect a burning sensation that has no center.

— Andrés Neuman, “Freckles and the Space Between”

1

Gerald, sun-kissed ten thousand times on the nose

and cheeks, didn’t stand a chance,

didn’t even know that the loss of his balls

had been plotted years in advance

by wiser and bigger buzzards than those

who now hover above his track

and at night light upon his back.

— Etheridge Knight, “For Freckle-Faced Gerald”

2

Ode to a Freckle above My Left Breast

Resigned to losing all that was mine

I brace myself before the bathroom mirror

in the hospital room. Afraid to look

at the wreckage where

my breast had been, what joy to see

you survived the assault! You perch above

the carnage where you always sat. Spared from the surgeon’s knife

you are a tiny flag of resistance

claiming territory, protecting a small part

of my chest from razing and reconstruction.

I press my palm over you, feel the heat rise

off my wounds. When the surgeon rounds,

I thrust a bouquet of lavender roses

from the overbed table into her arms,

the only thanks-offering I have for you.

by Amy Haddad,

(featured on The Slowdown)

3

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

— Gerald Manley Hopkins, “Pied Beauty”

4

The section titled “Freckles and the Space Between” by Andrés Neuman, collected in his rousing book, Sensitive Anatomy, a series of textual sketches that caress each part of the human body.

5

I don’t know how long my silence lasted. And I use “silence” perfectly aware that it’s not entirely accurate but that it’ll be easier for you understand that way. You can write in your notes: “Claims to have kept silent.” Or ask the señora: “Did your maid fall silent?” To which the señora will reply: “I don’t recall any silence.” Because I doubt a woman like her would ever recognize a silence like mine.

You might never have given it any thought, but words have a specific order. Cause–outcome. Beginning–ending. You can’t NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION just arrange them any old way. When we speak, each word has to stand apart from the one before, like children lined up at the classroom door. From small to big, short to tall—the words go in a particular order. With silence, on the other hand, all words exist at once: gentle and harsh, warm and cold.

— Alia Trabucco Zerán, CLEAN (translated by Sophie Hughes)

6

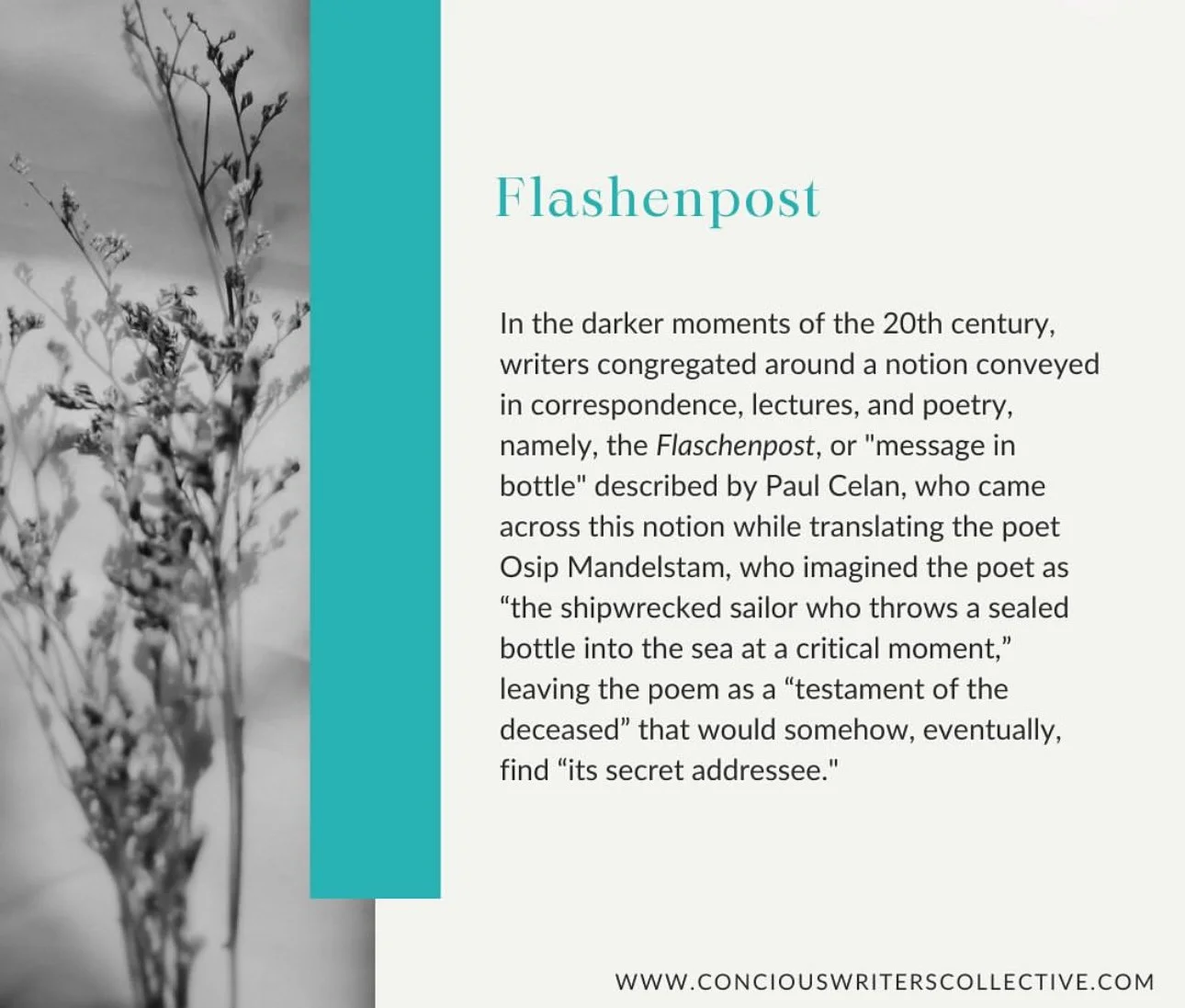

From my notebooks, a phrase I copied out as written by Ilya Gutner: Mandelstam’s beloved granite slabs with little freckles of foreign substances inside them…

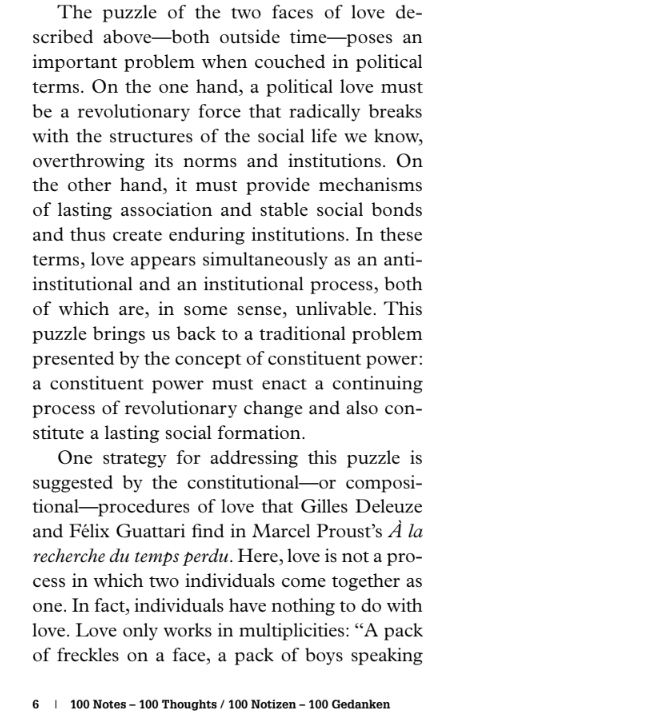

Elsewhere, a freckle in Michael Hardt’s Documenta pamphlet, “The Procedures of Love”:

7

At the end of the contest, contestants received prizes like cosmetic sets containing gold dust, or soaps touted to eliminate freckles and blemishes.

— Ha Seong-nan, WAFERS (translated by Janet Kong)

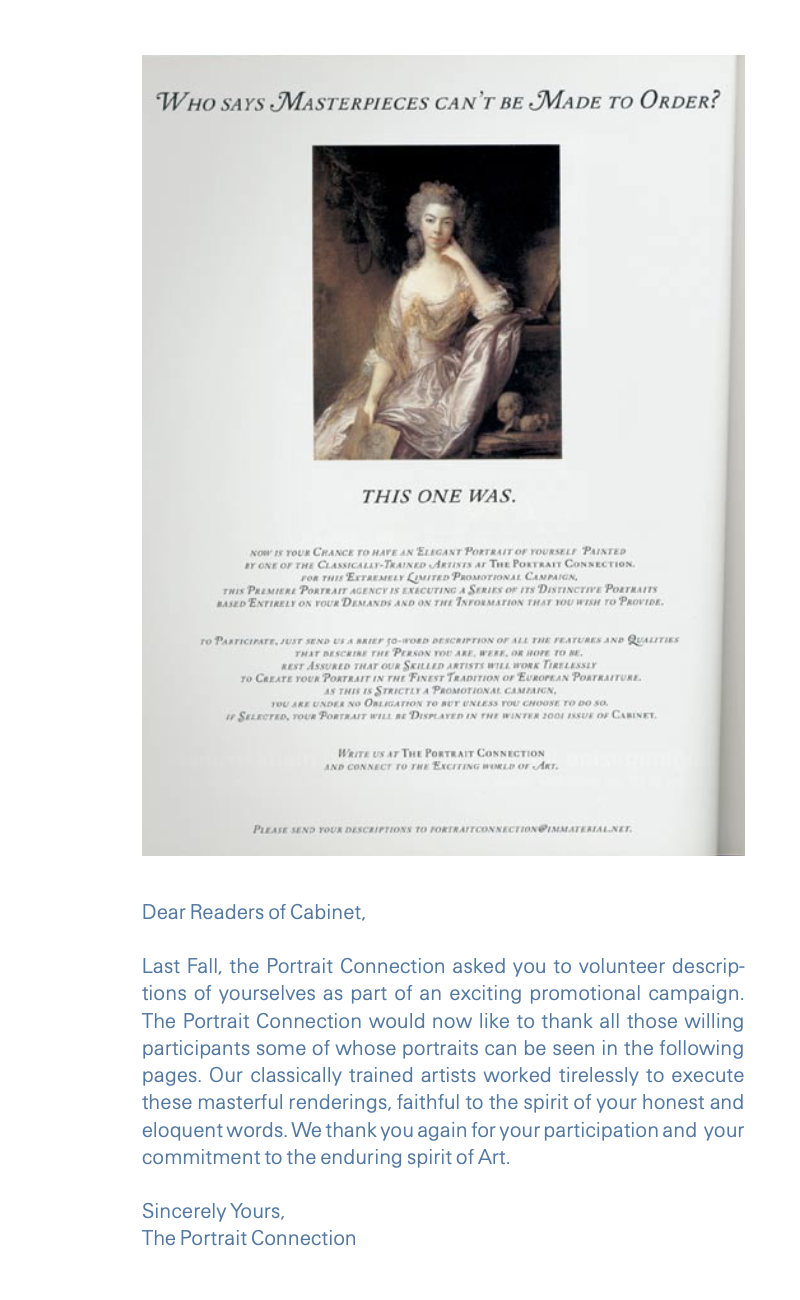

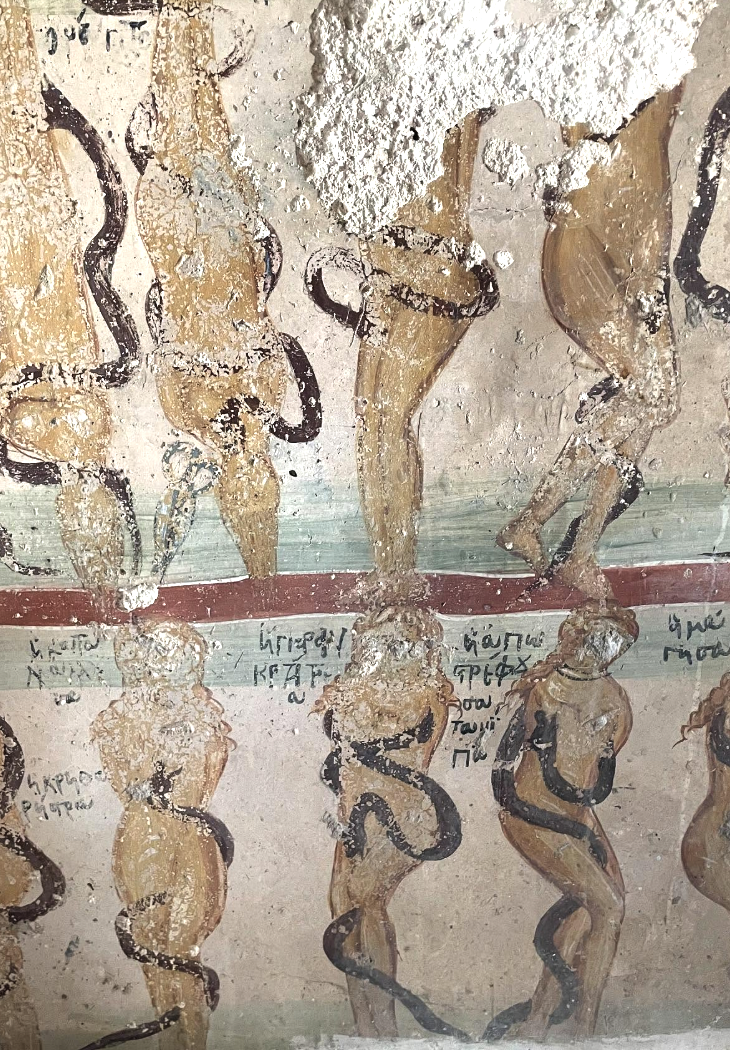

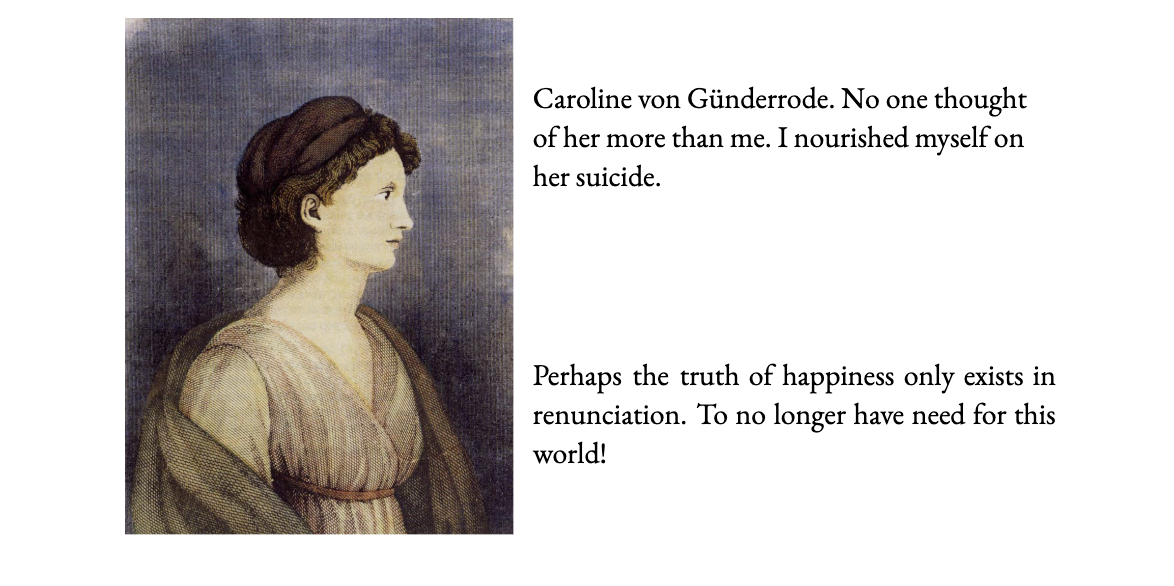

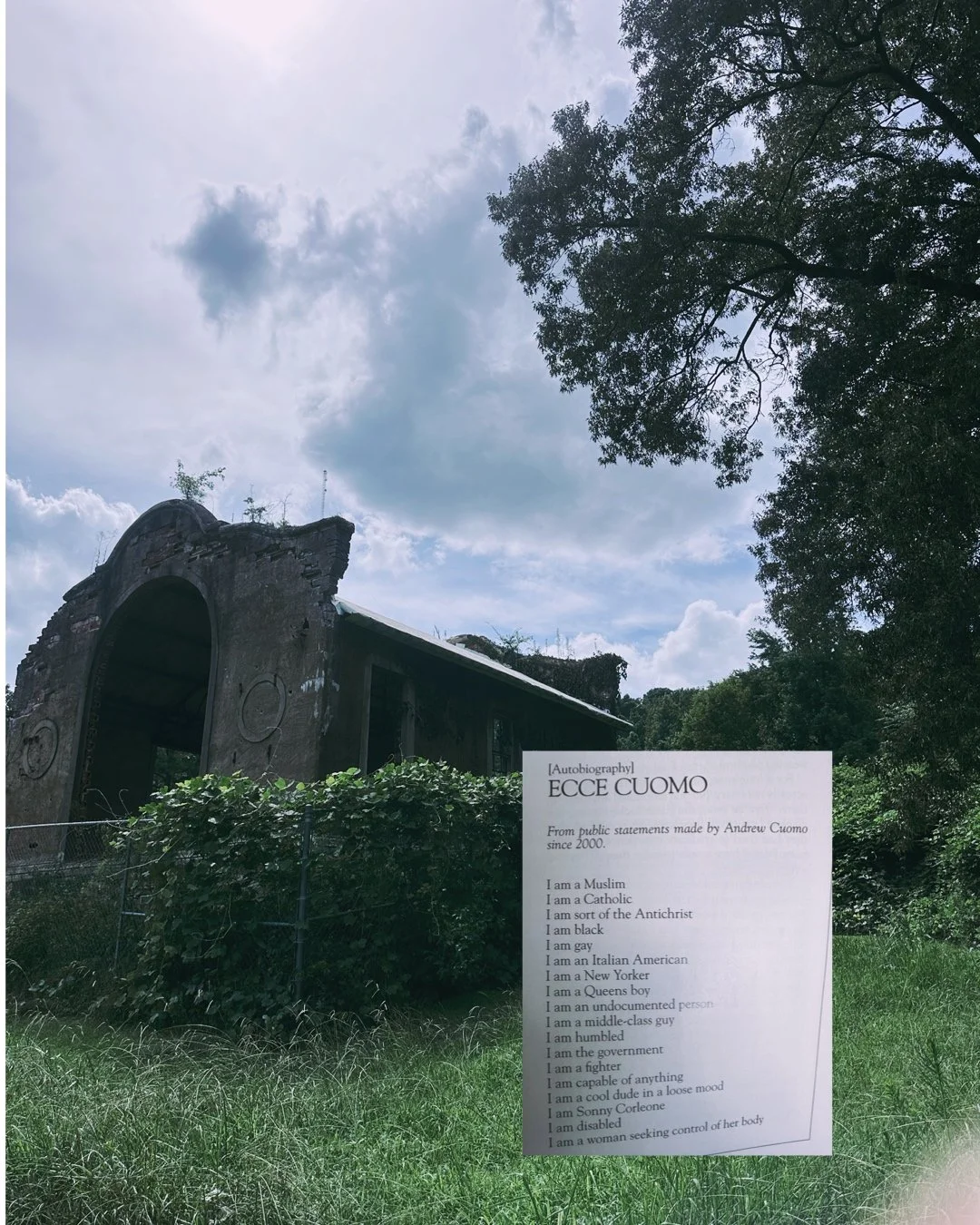

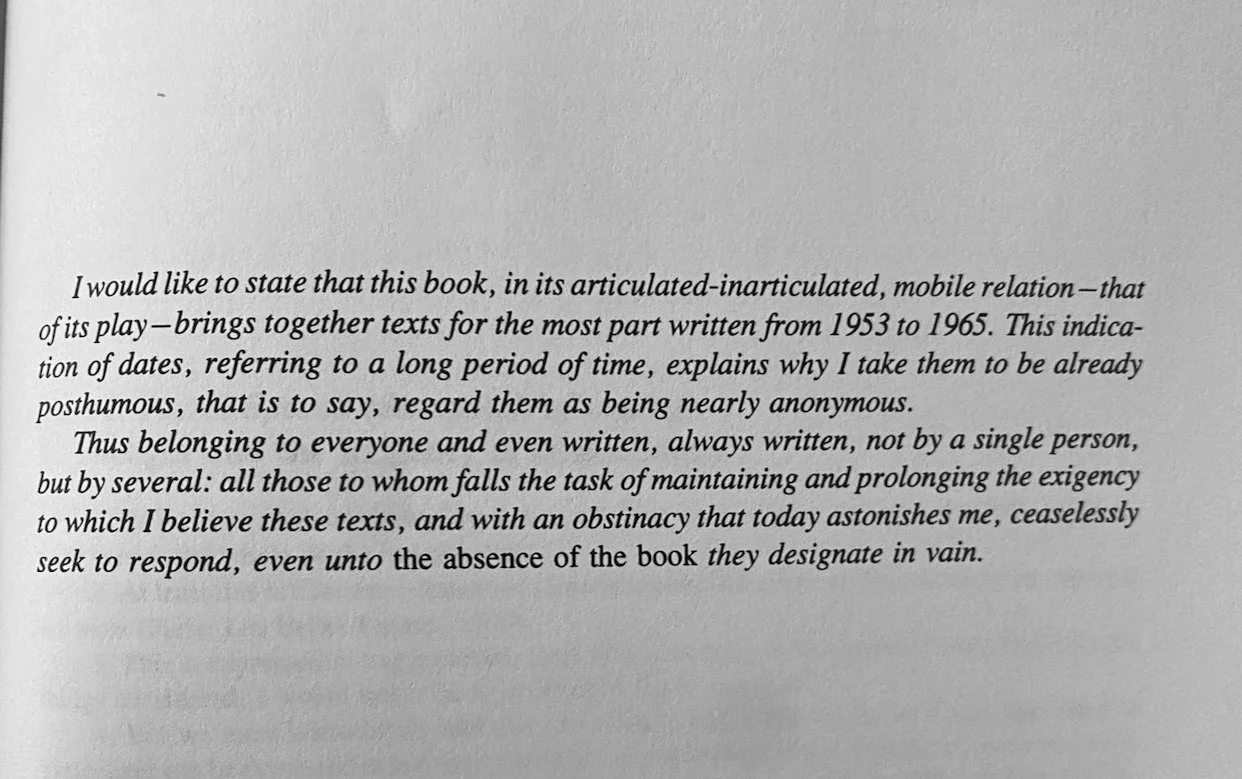

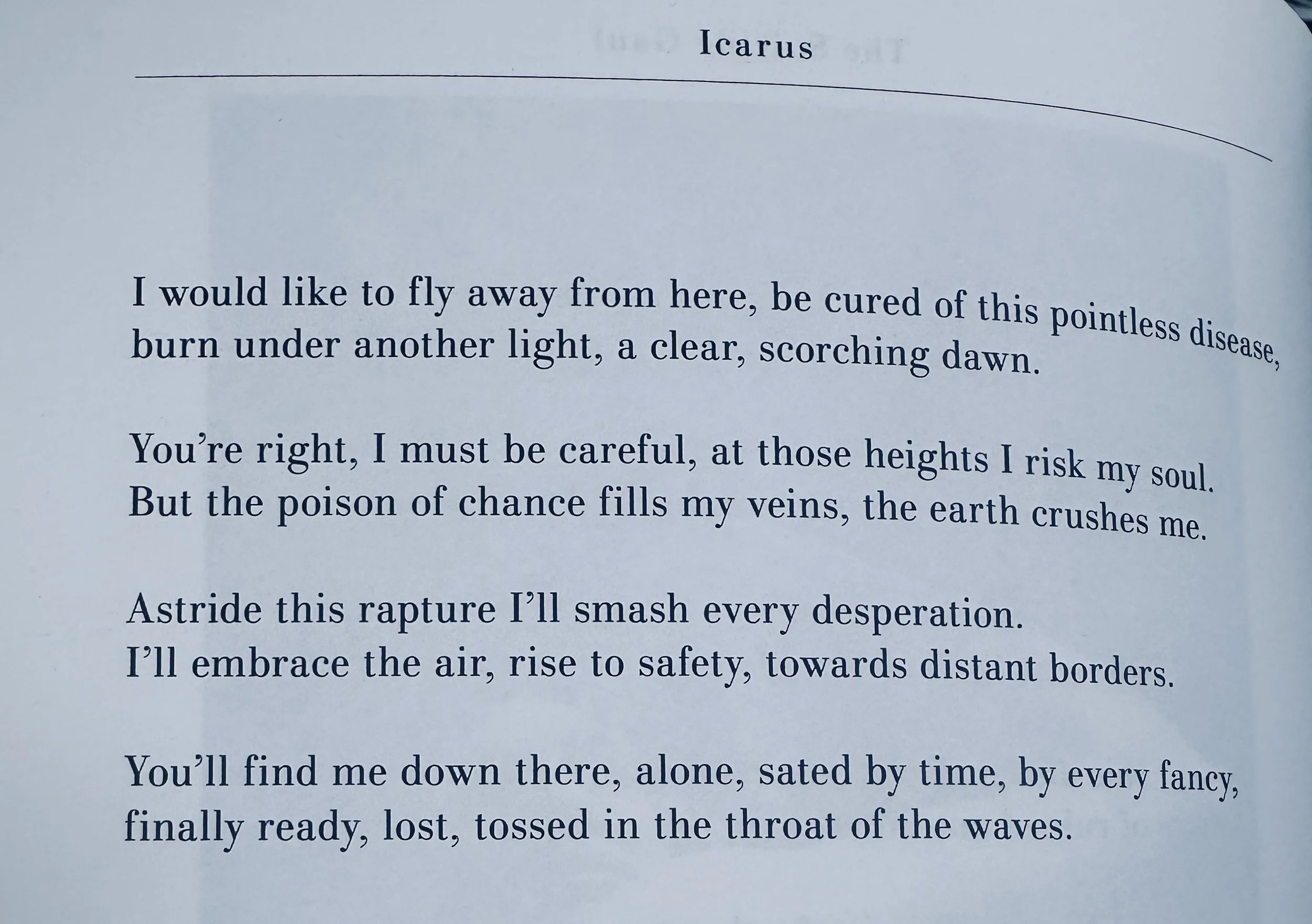

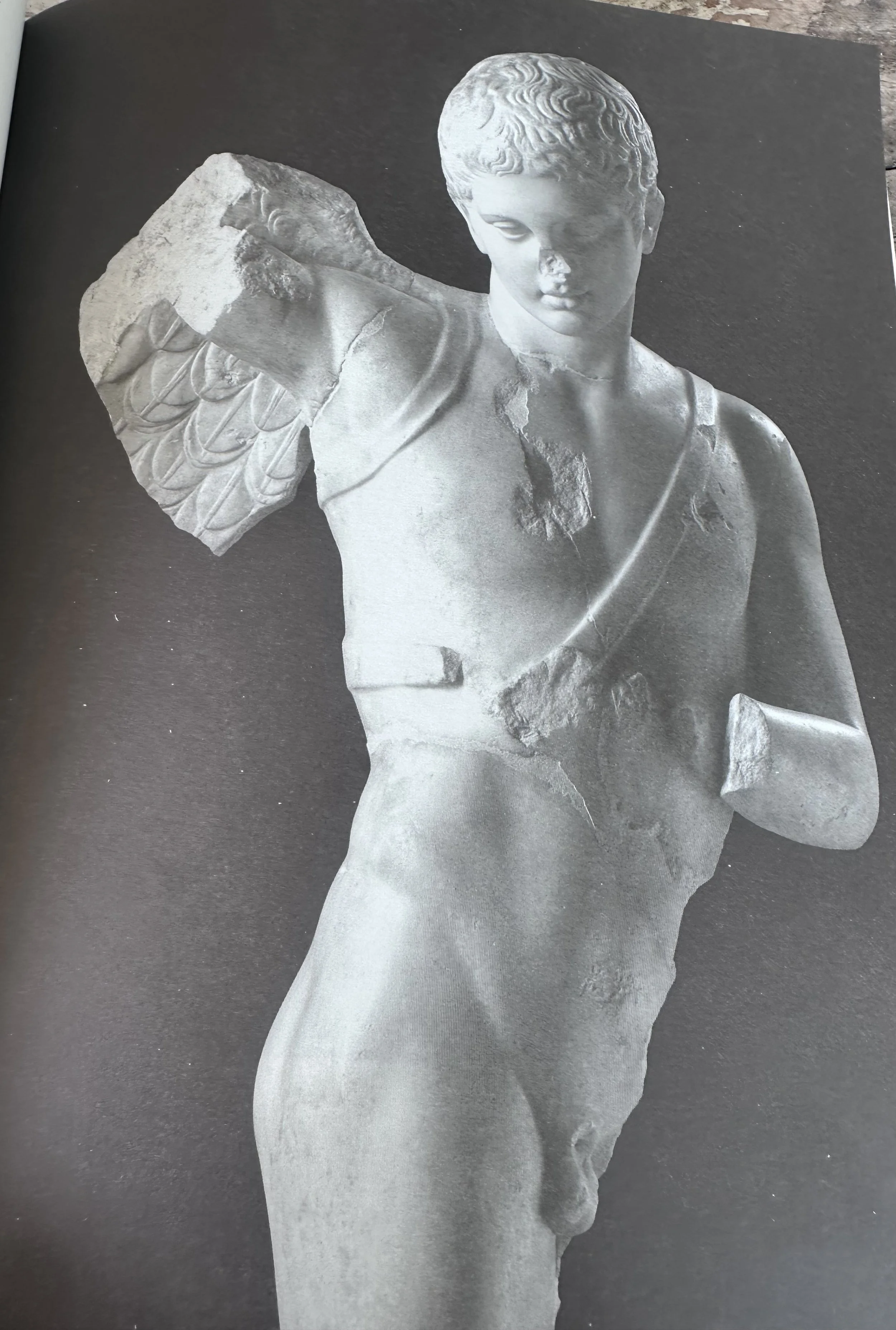

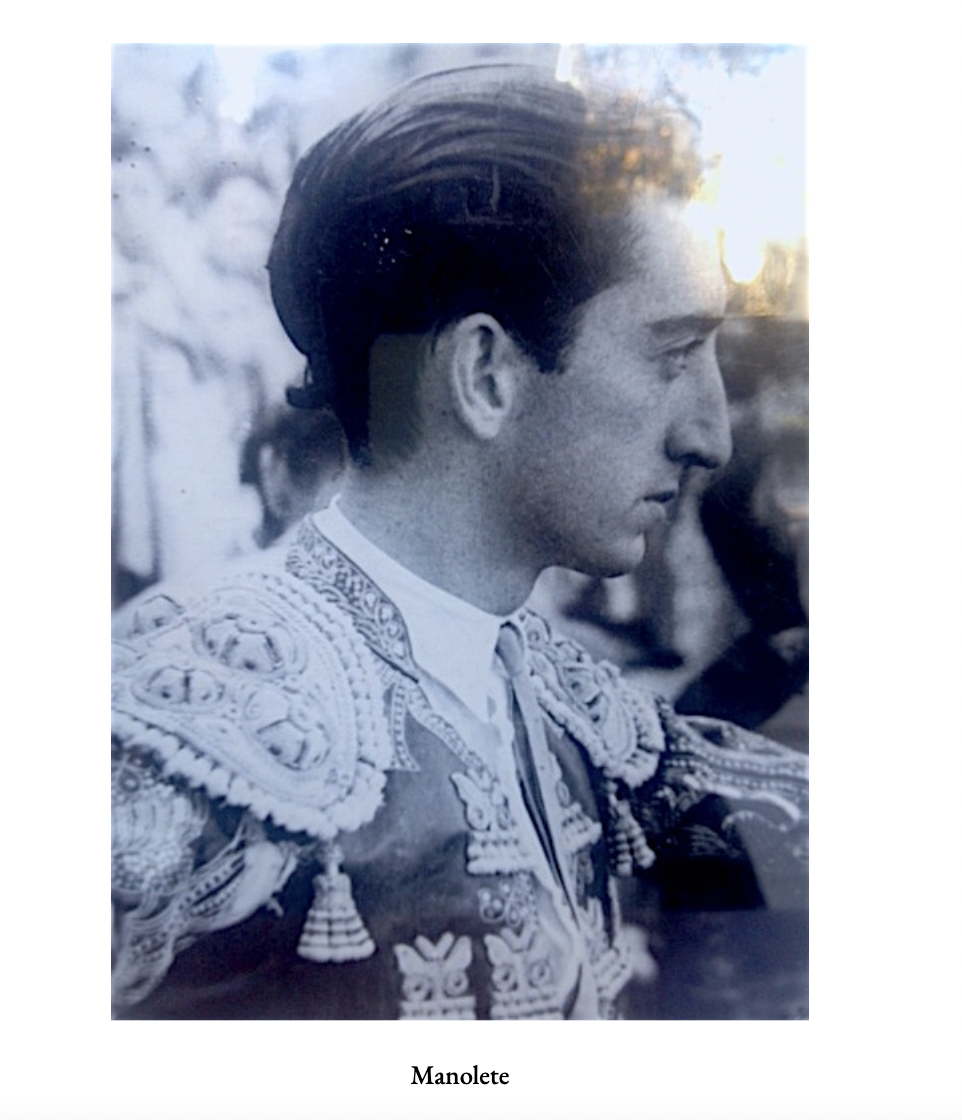

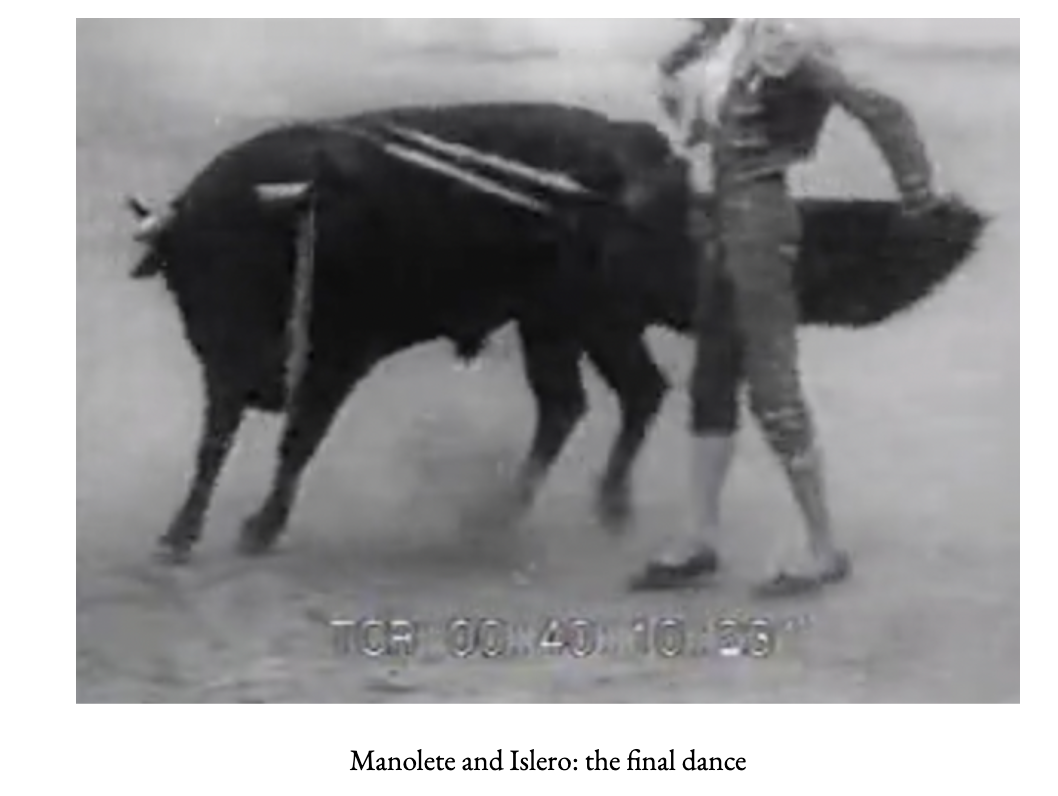

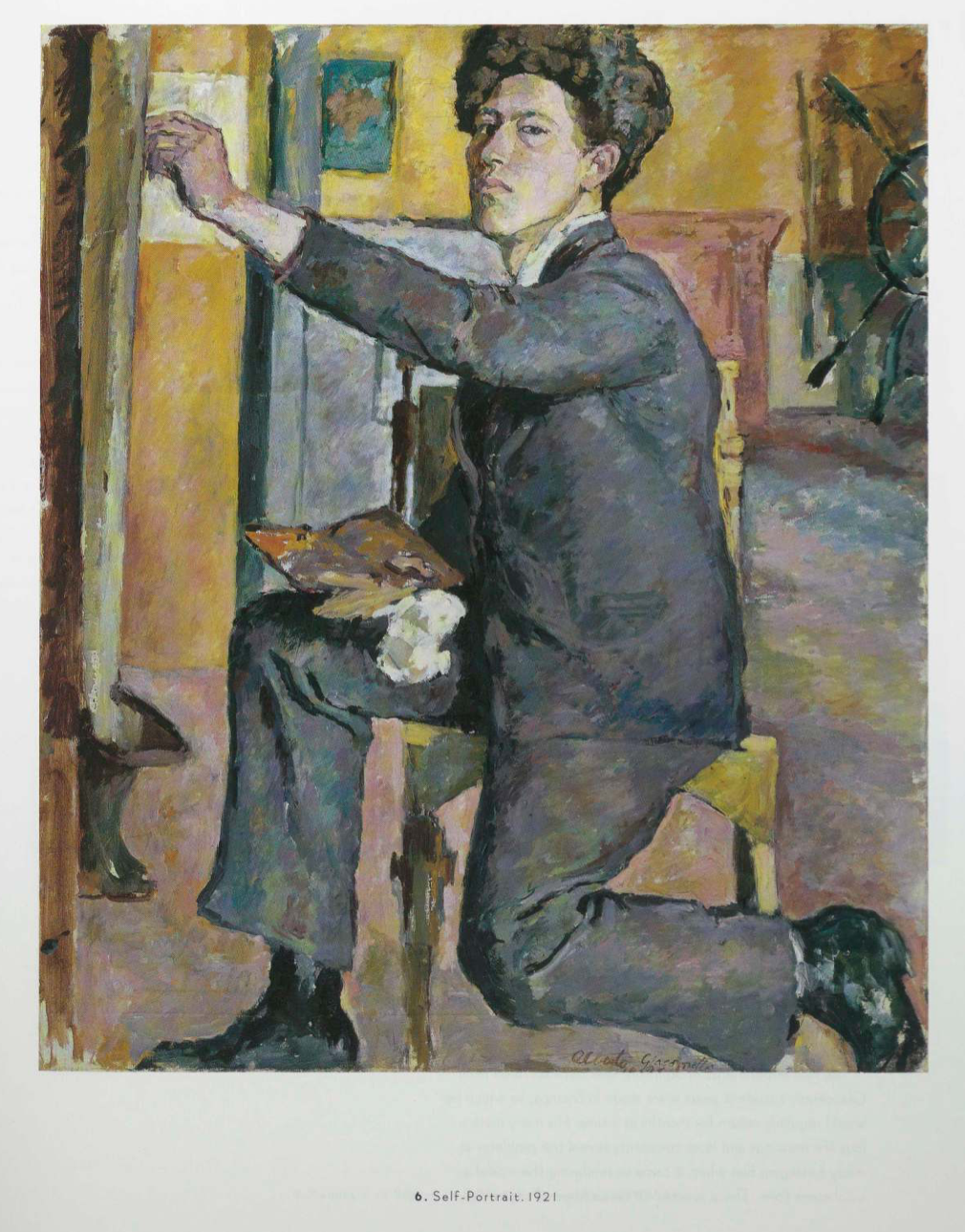

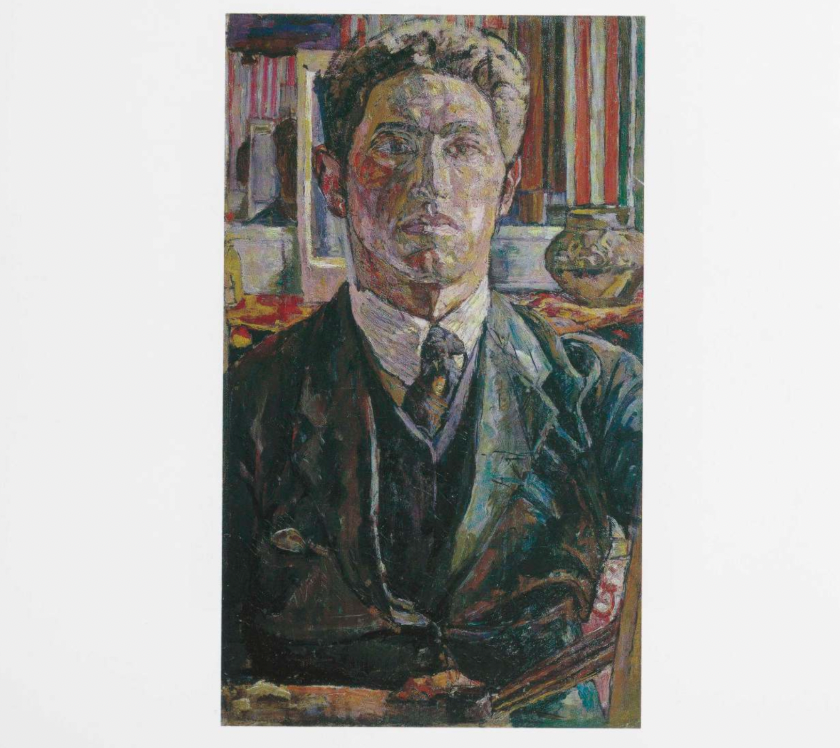

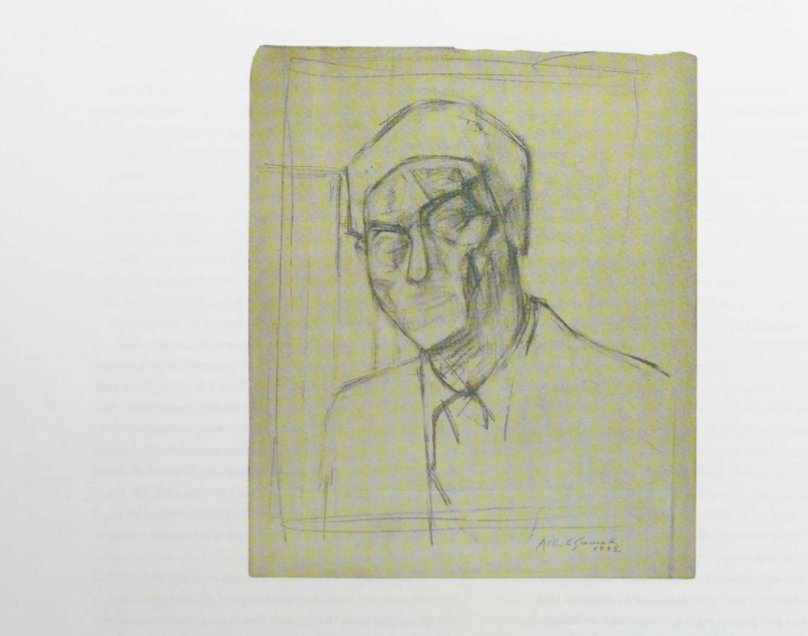

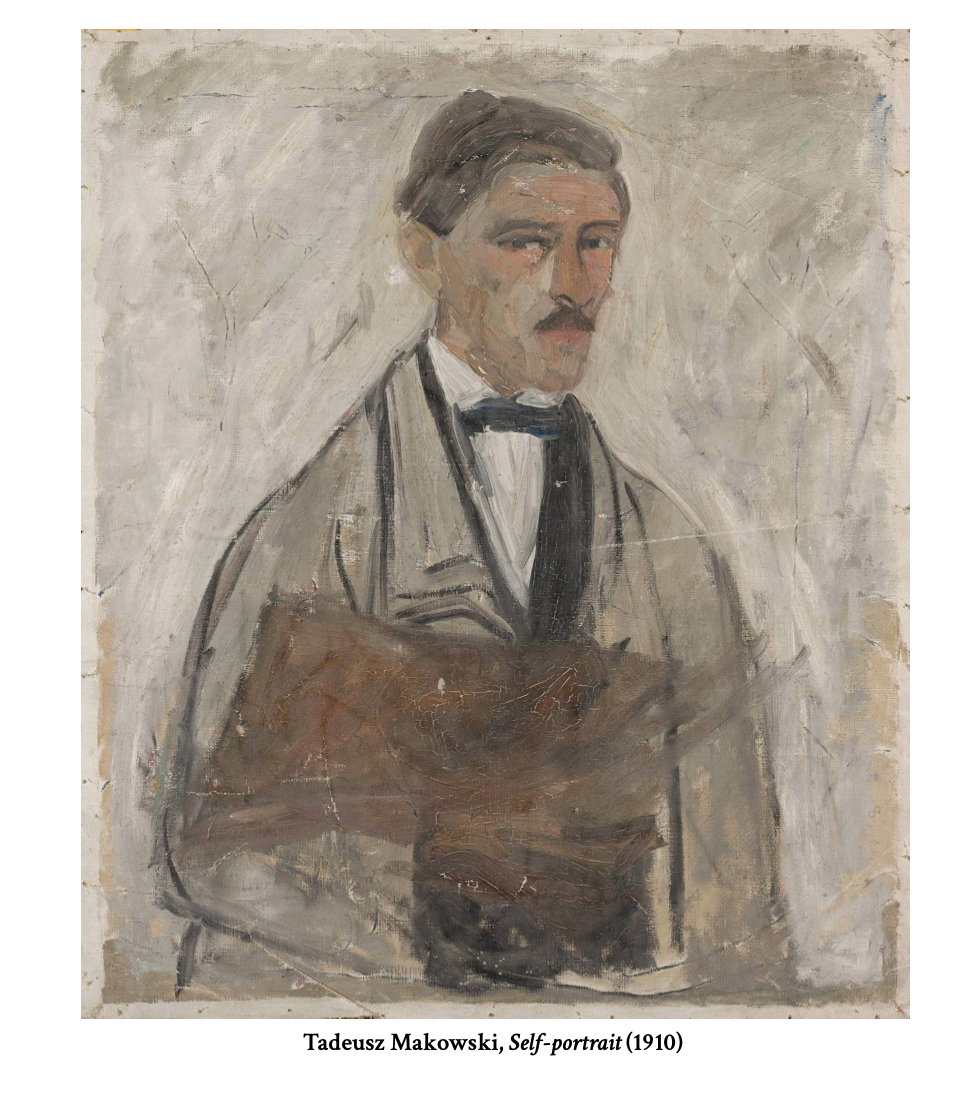

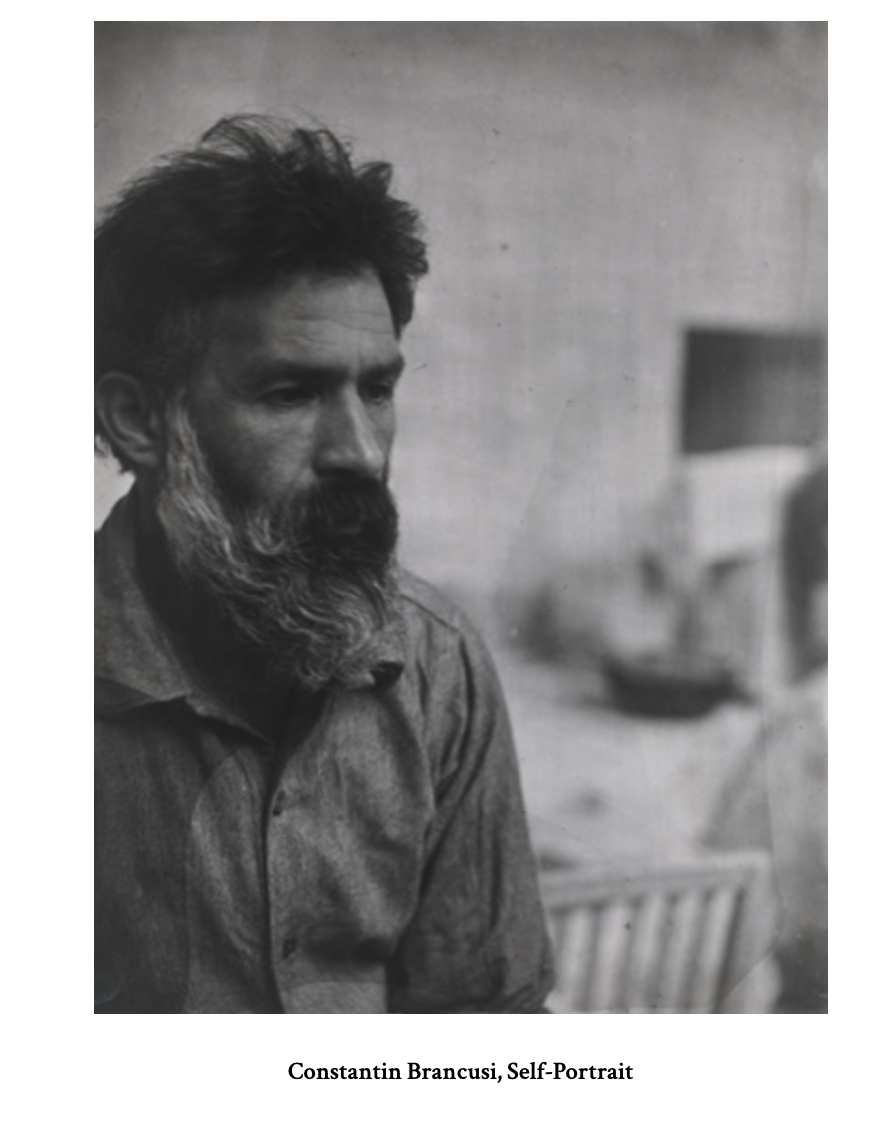

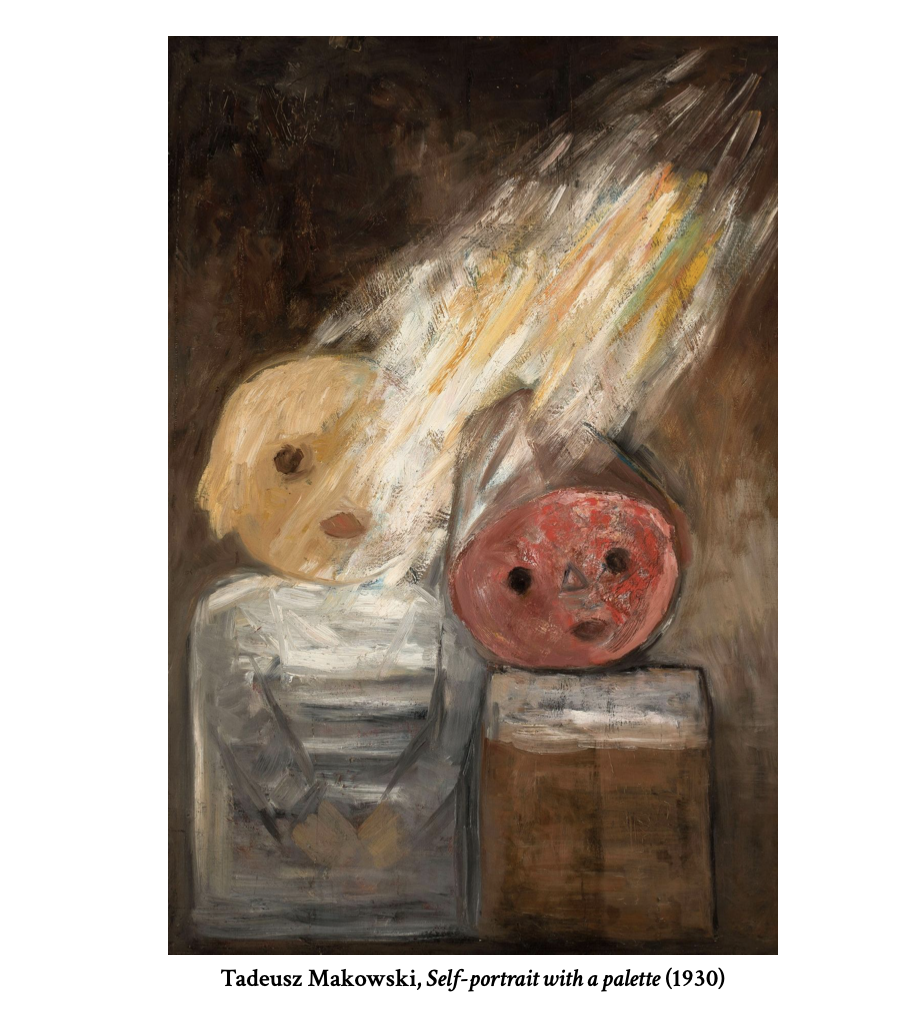

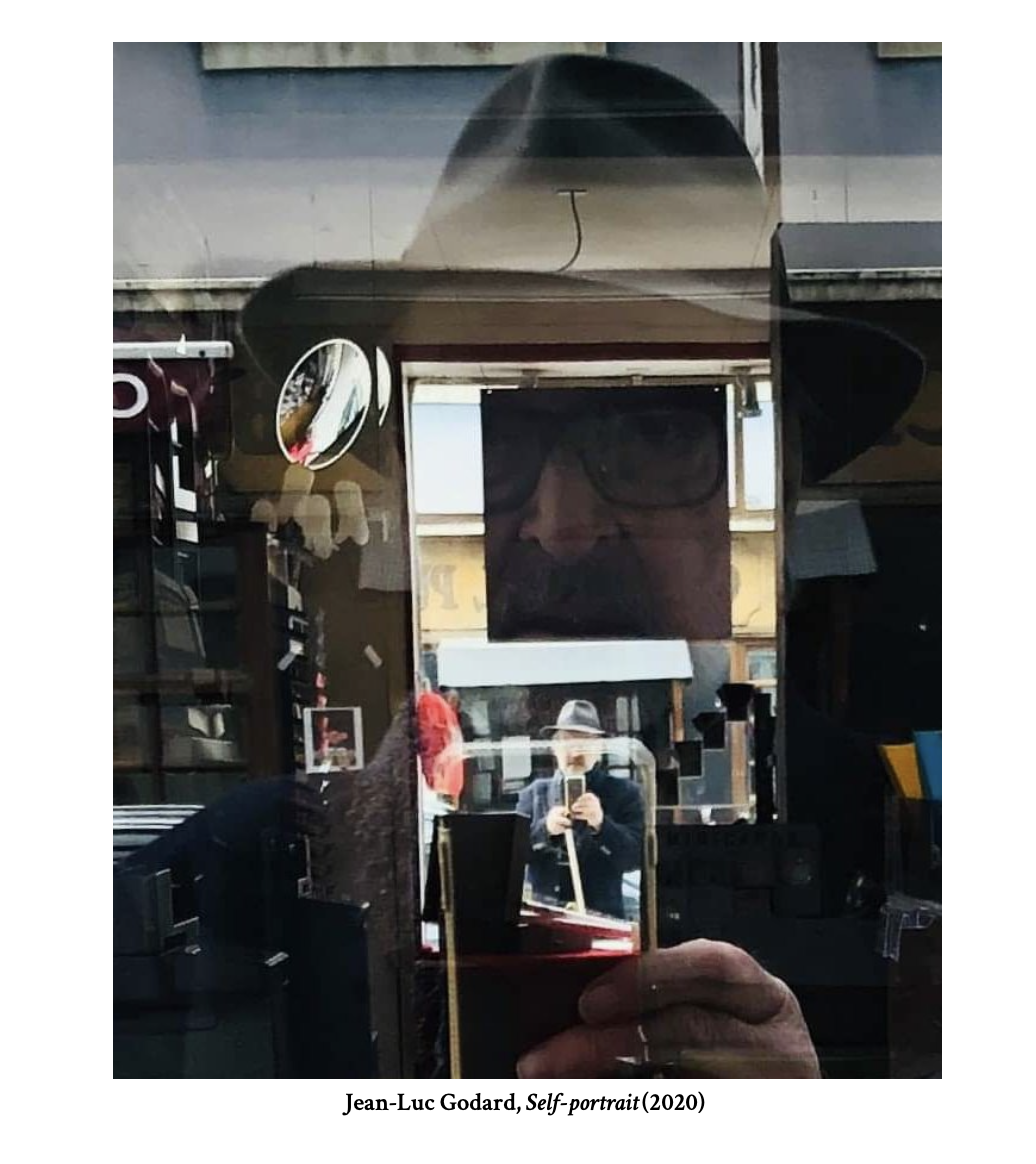

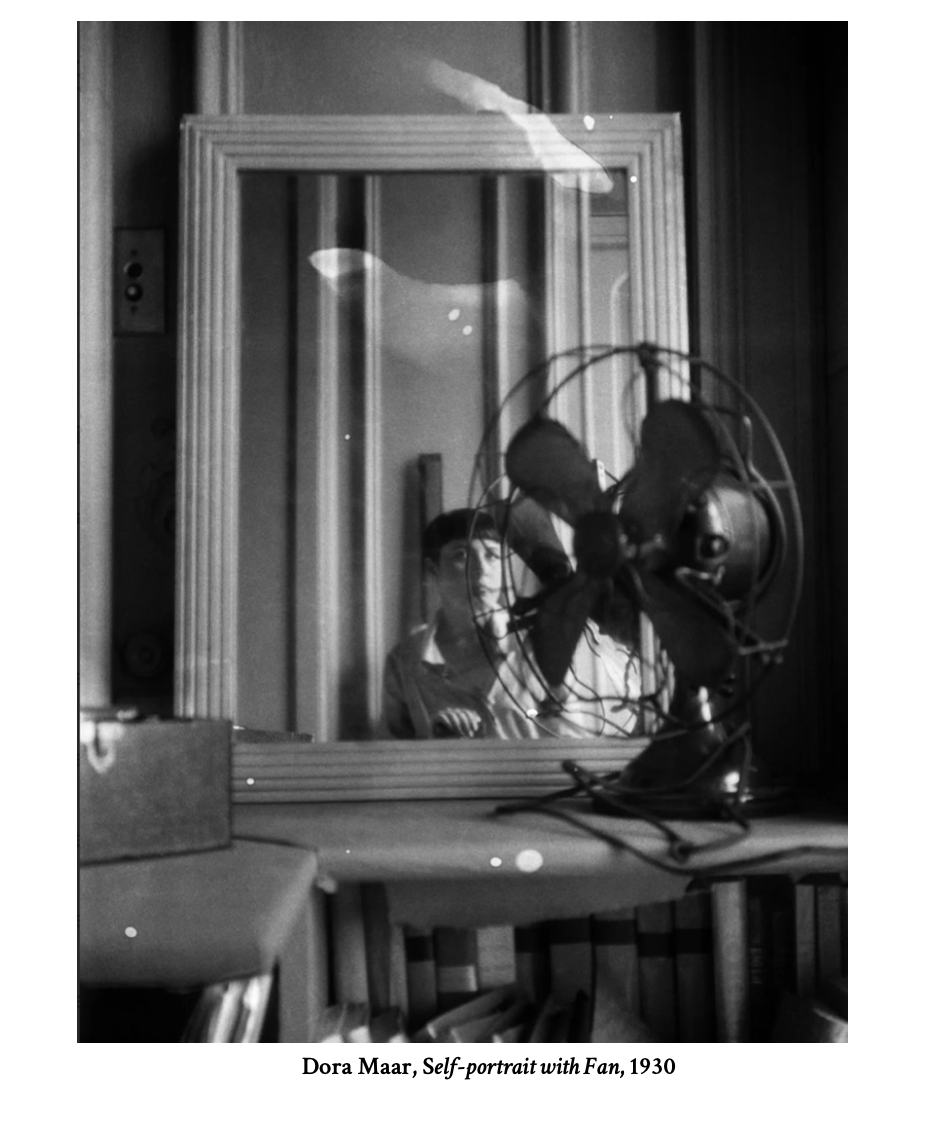

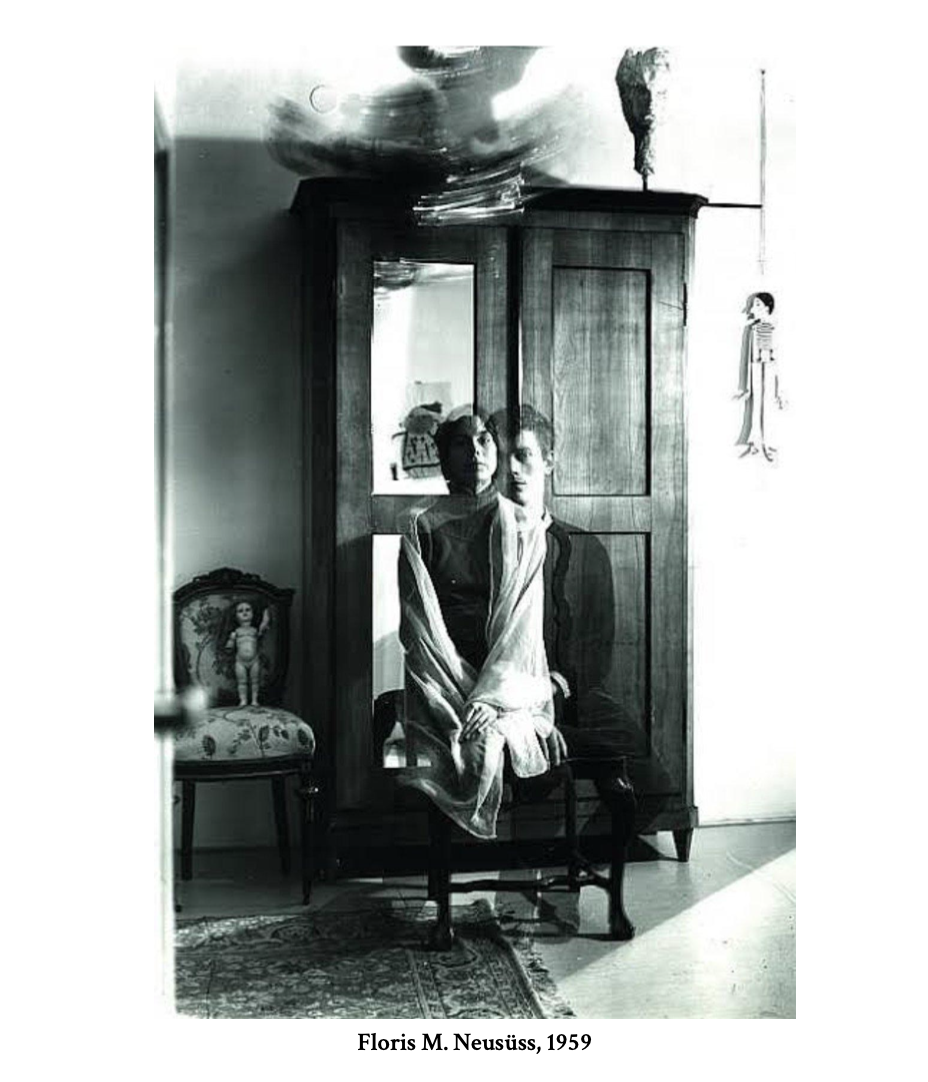

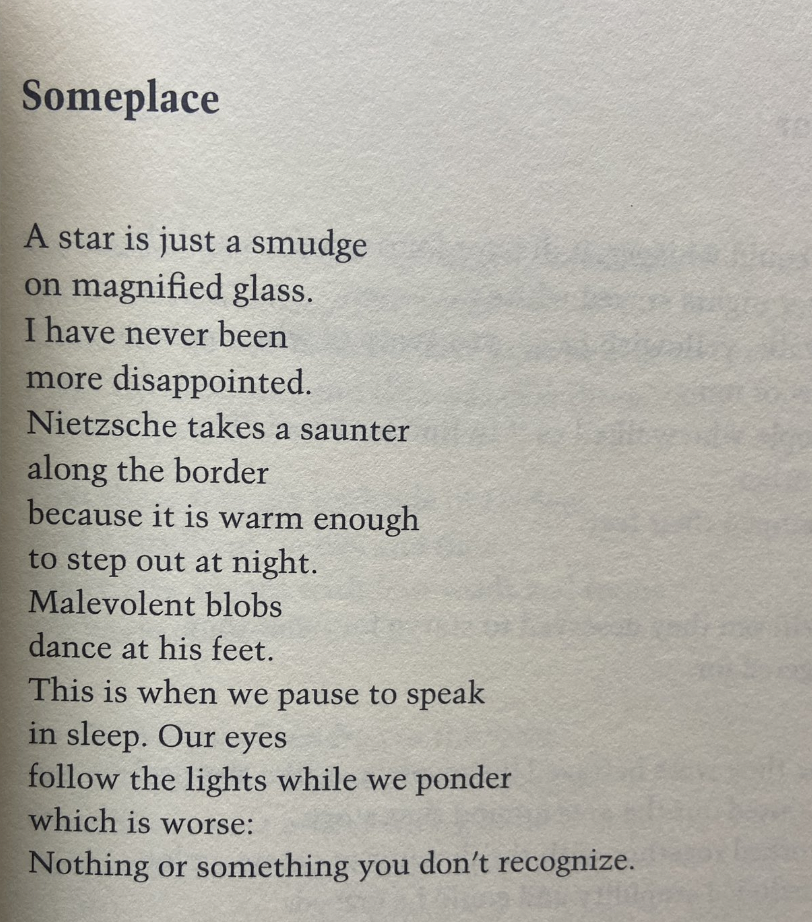

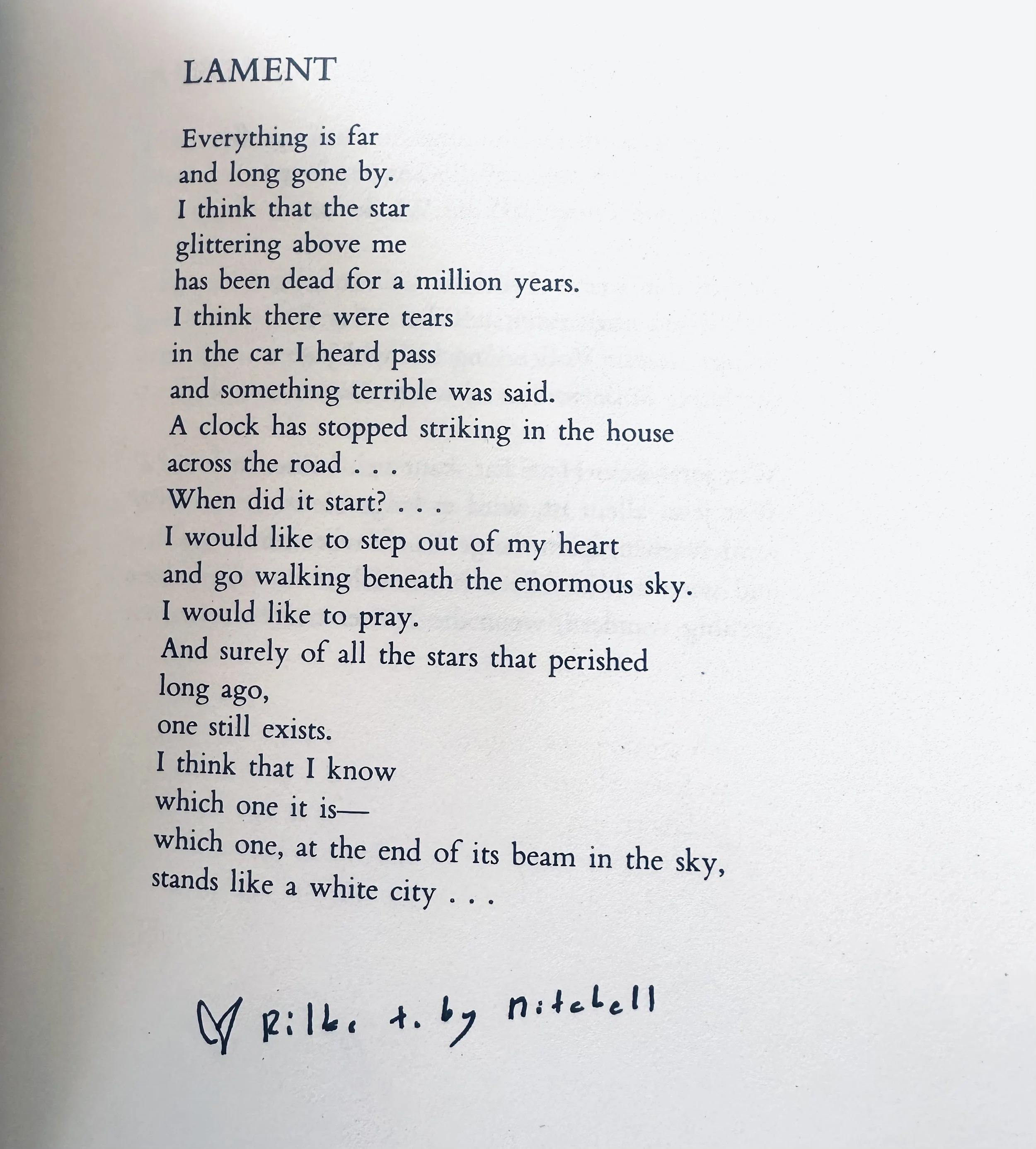

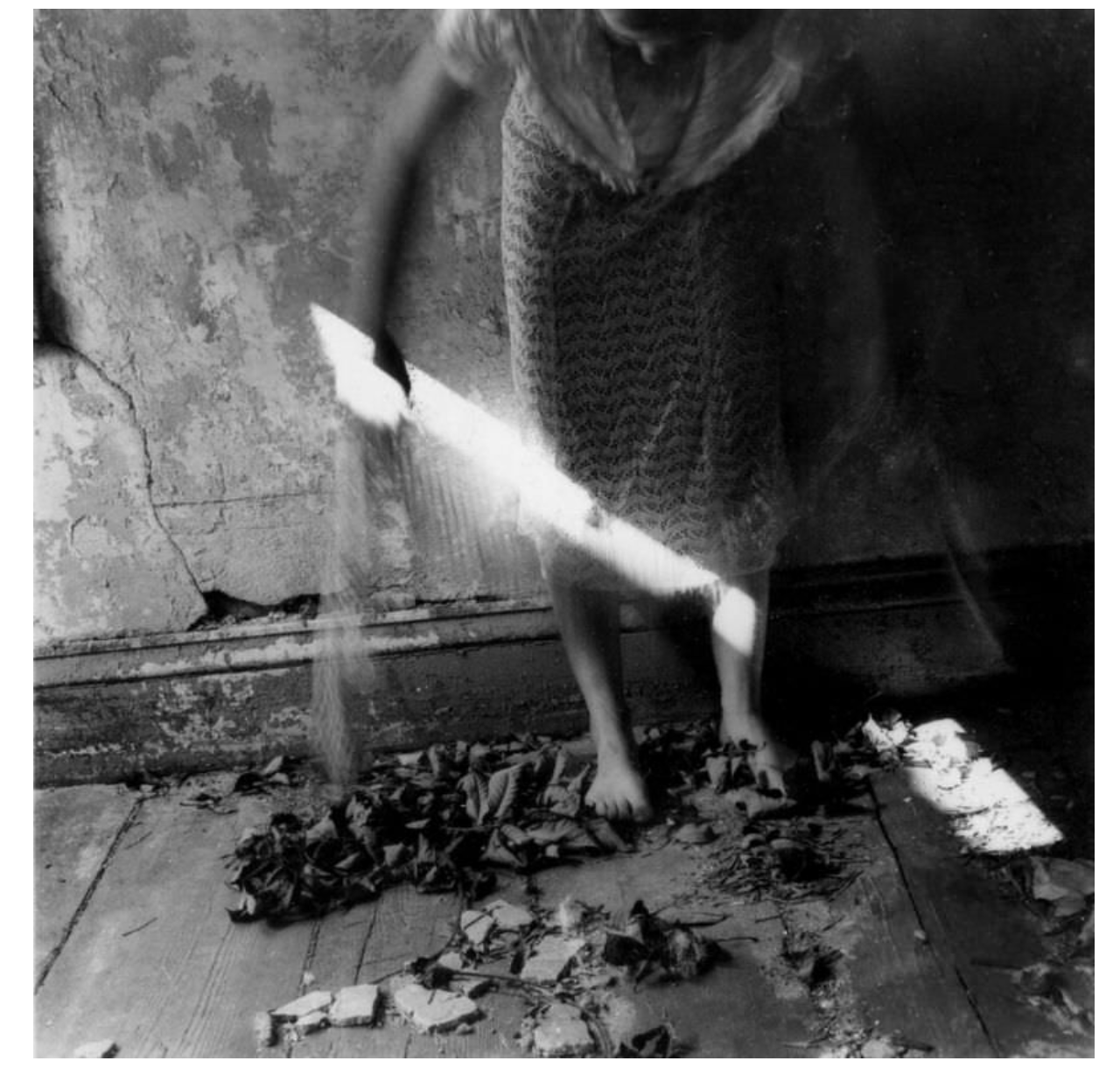

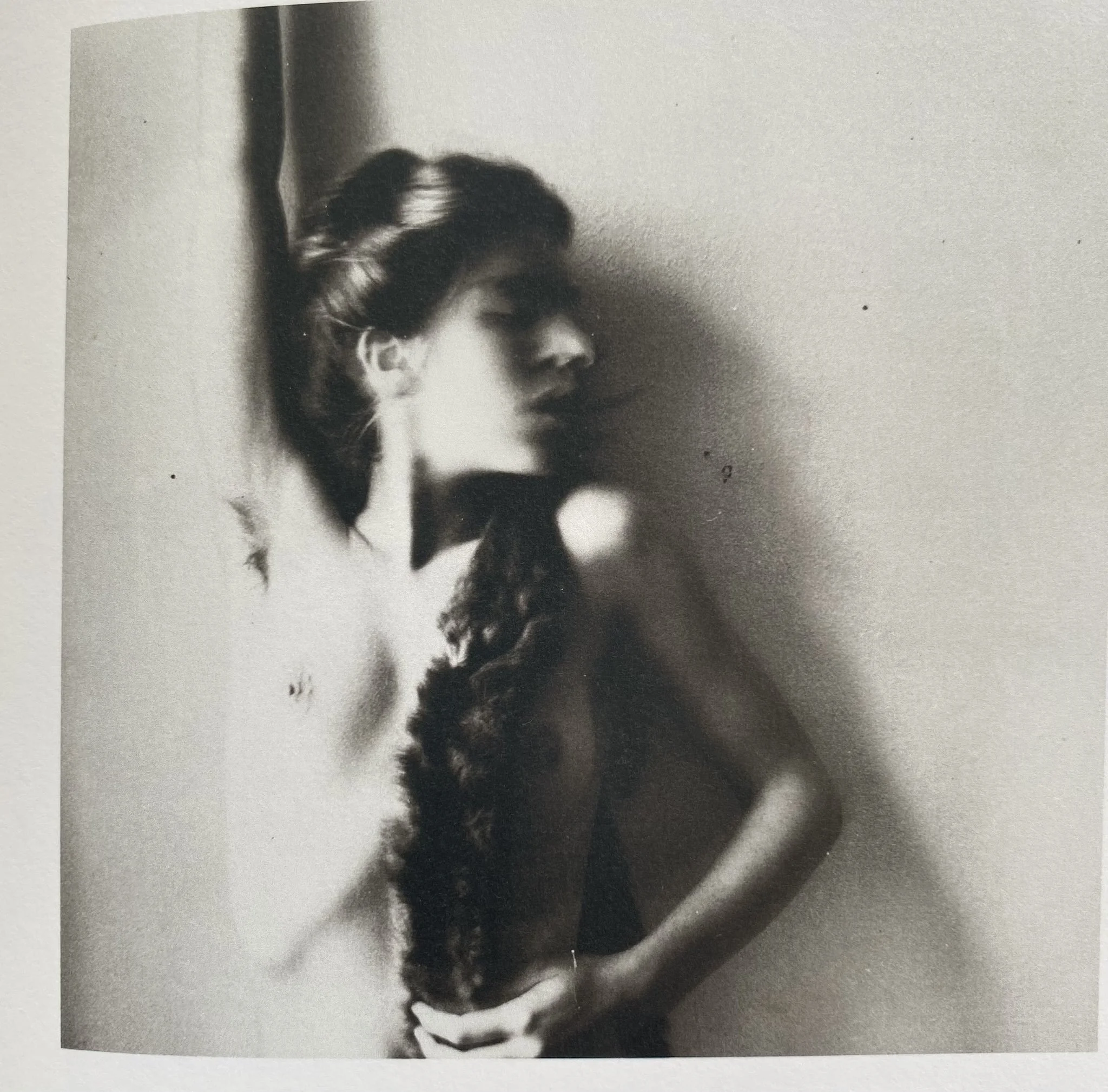

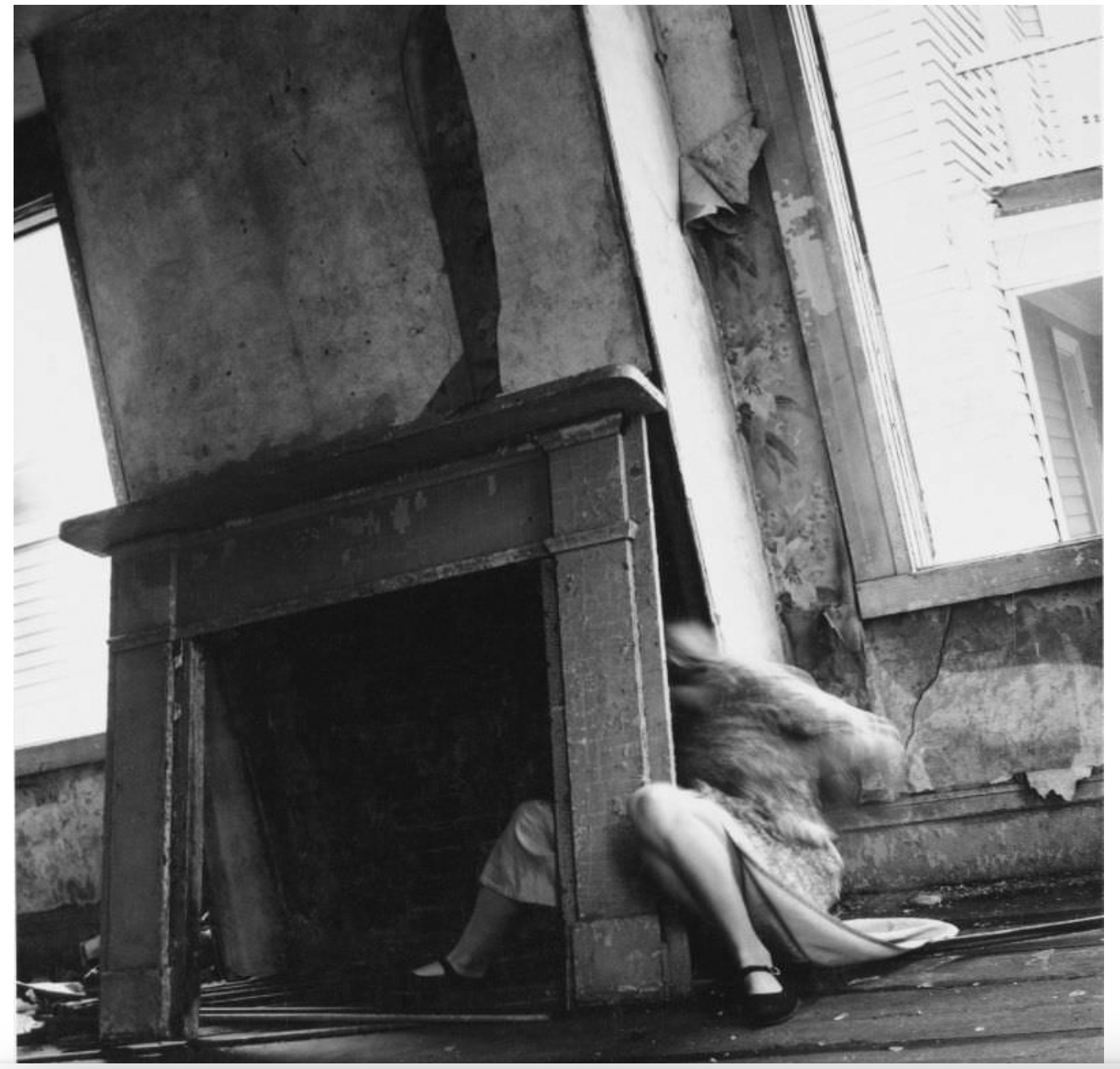

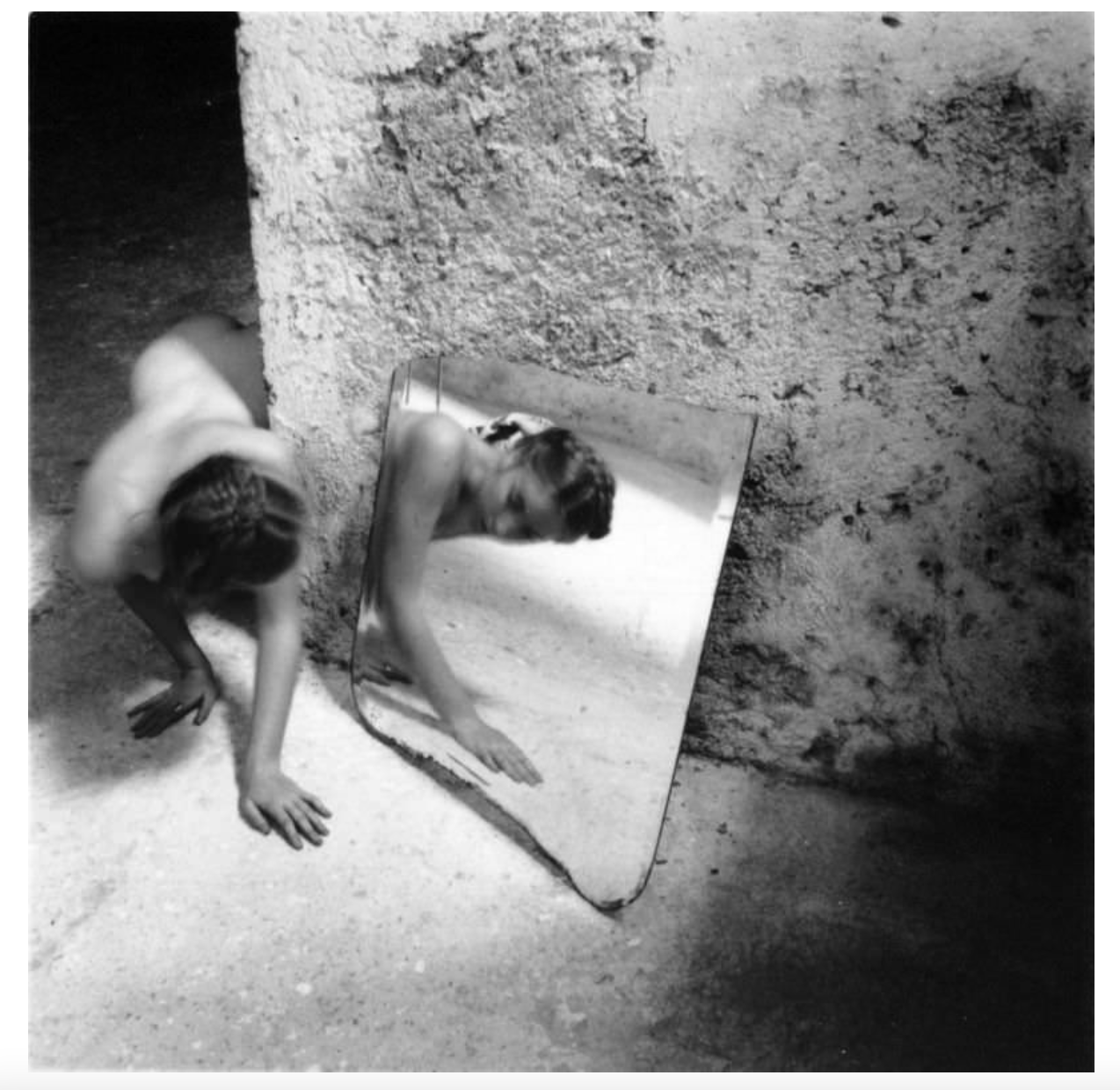

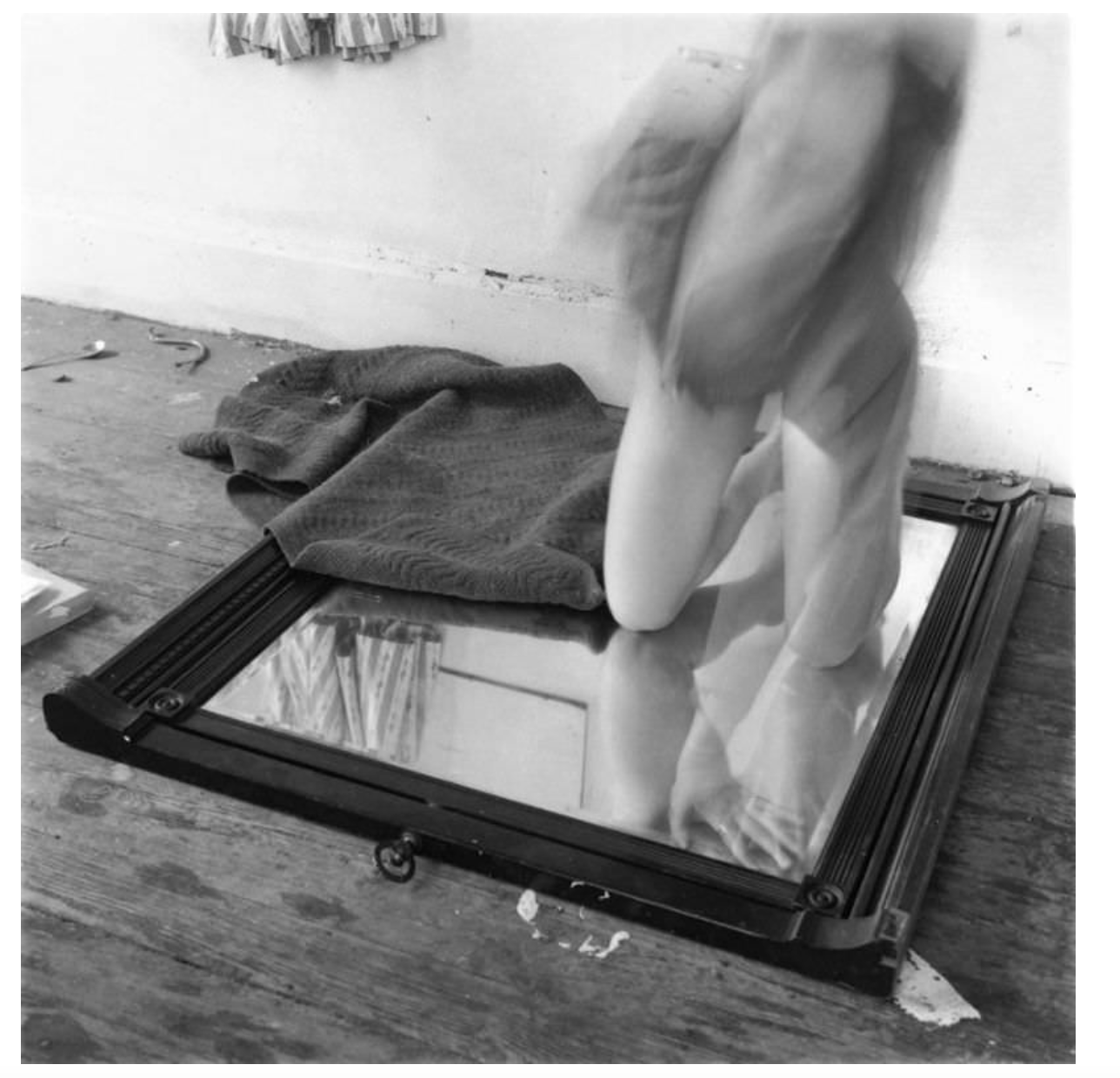

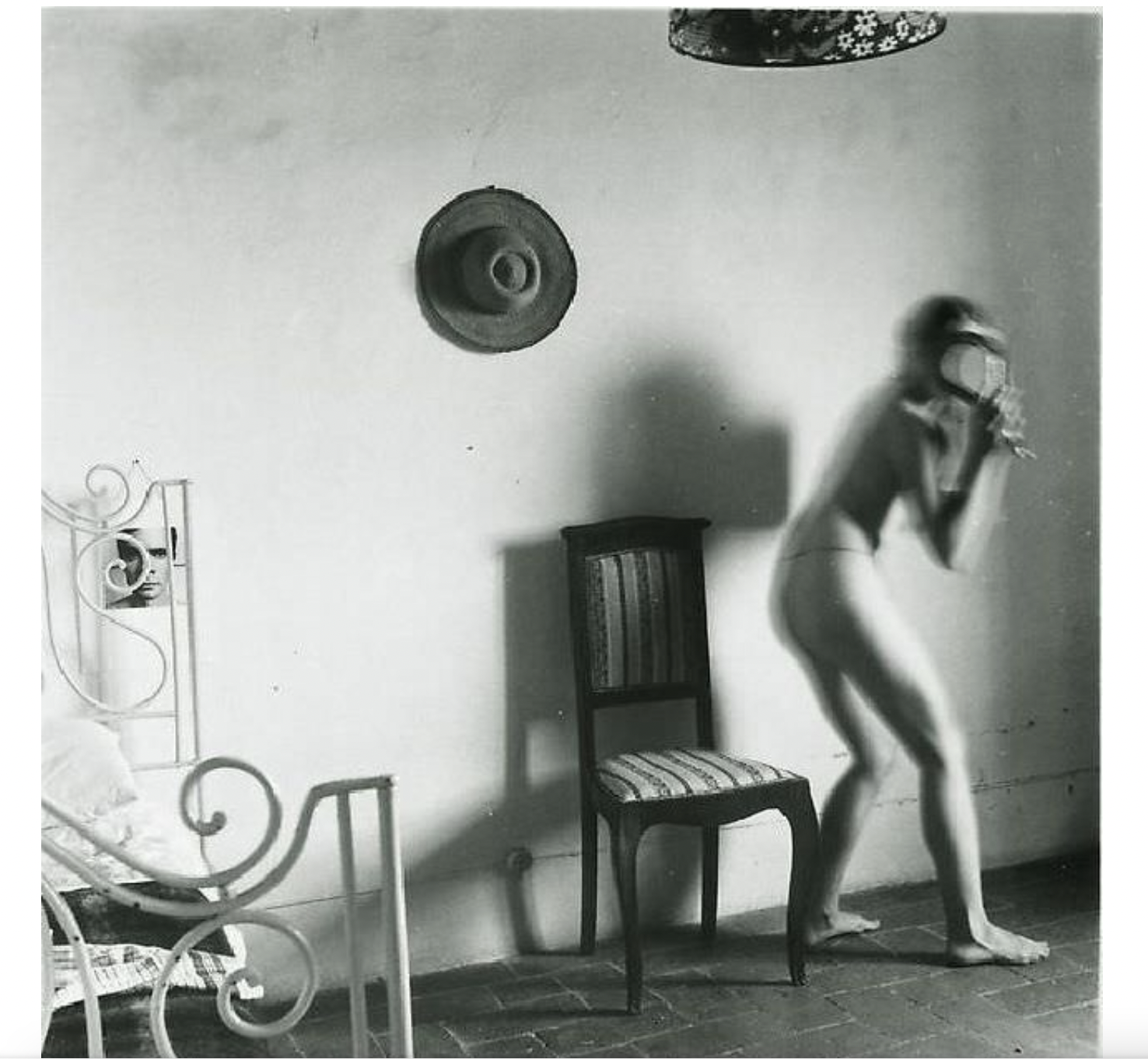

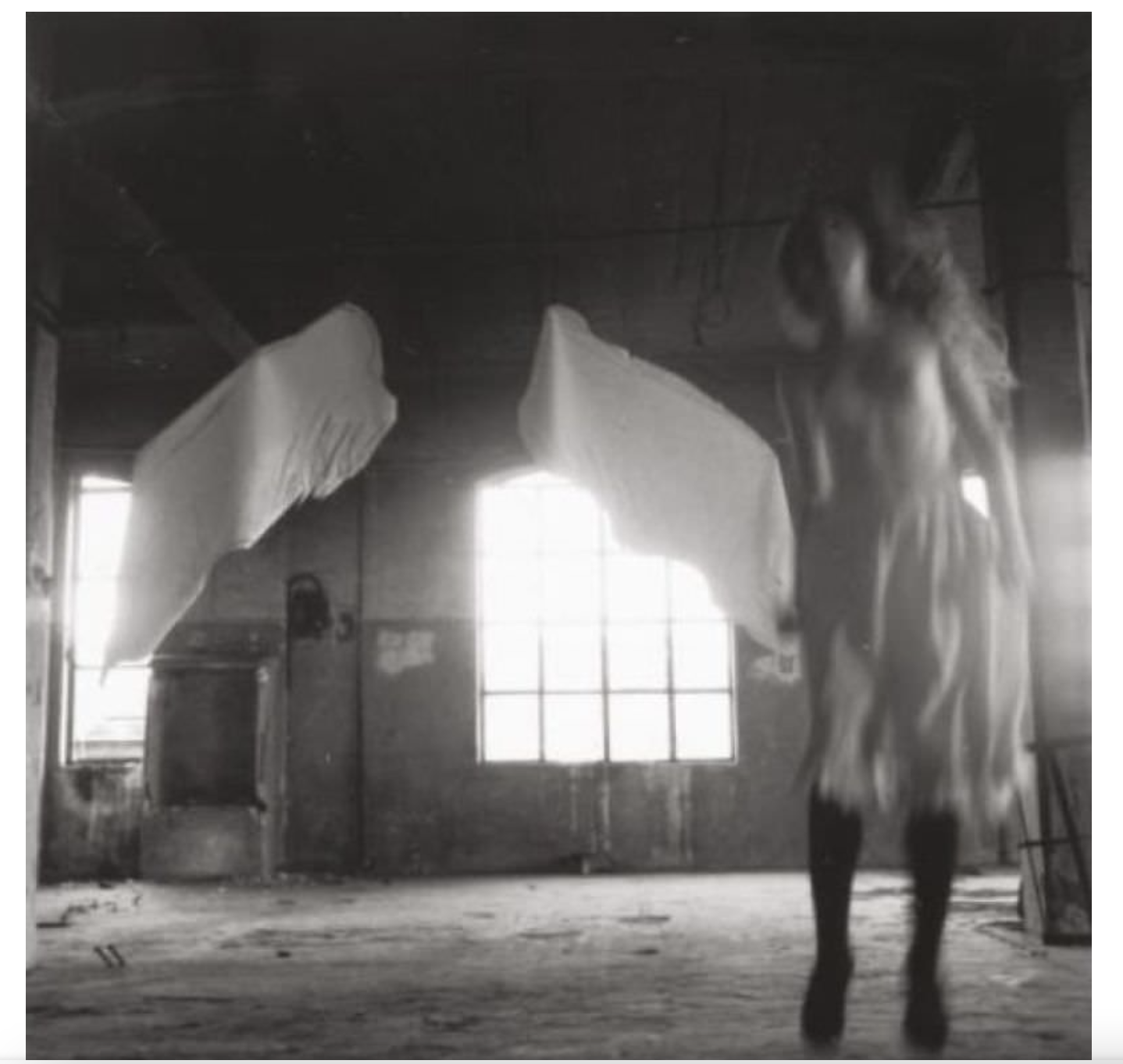

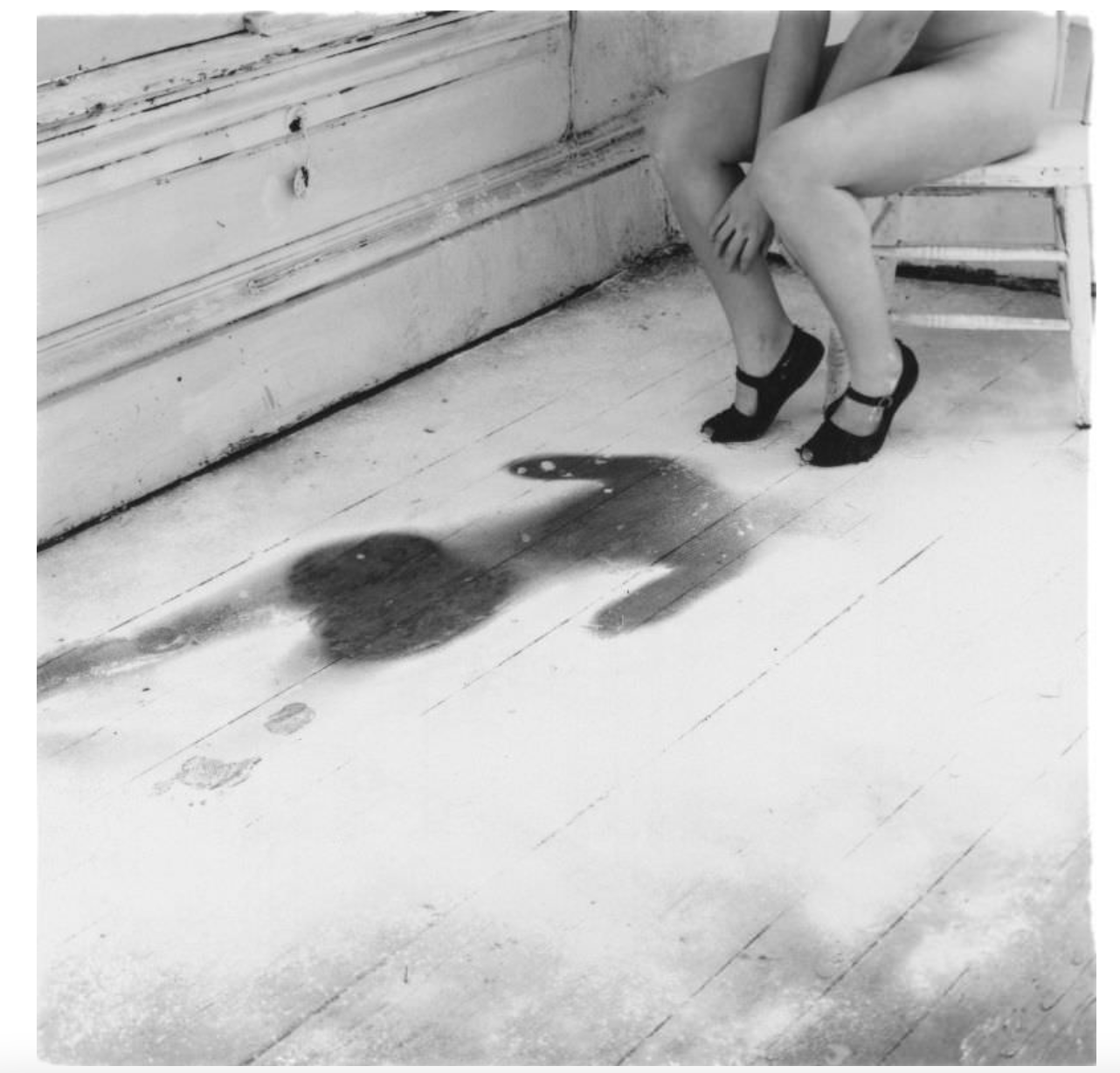

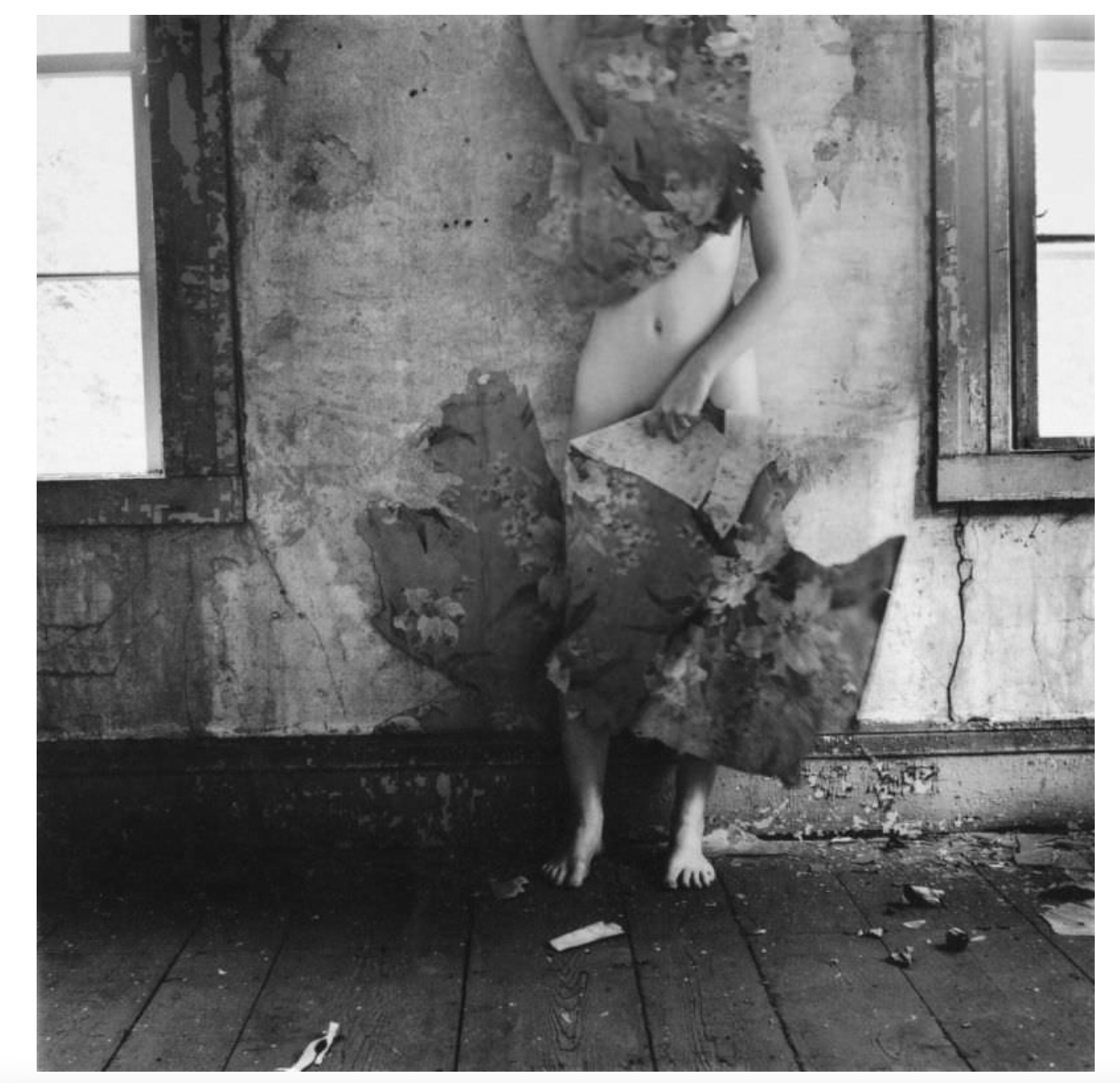

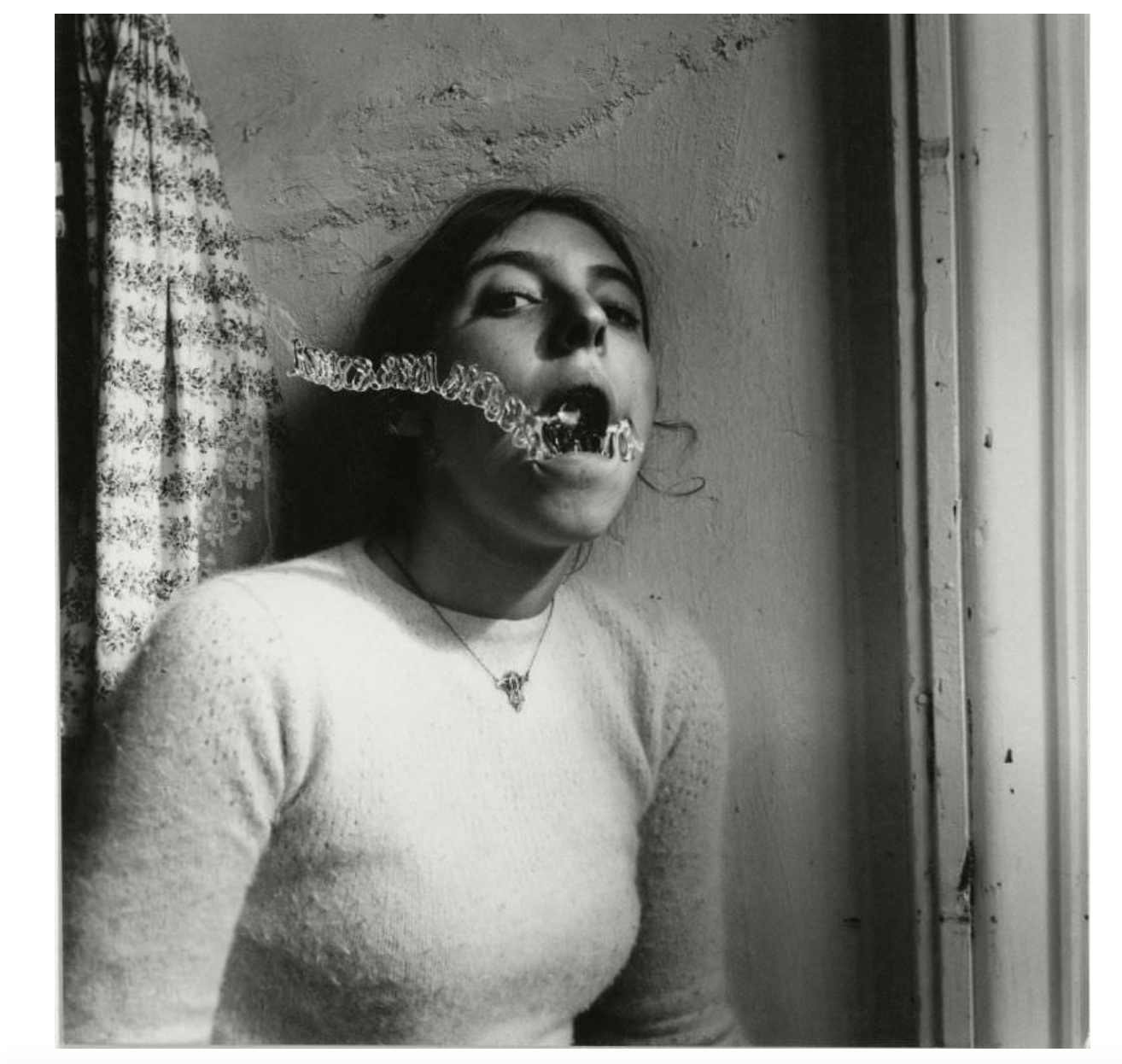

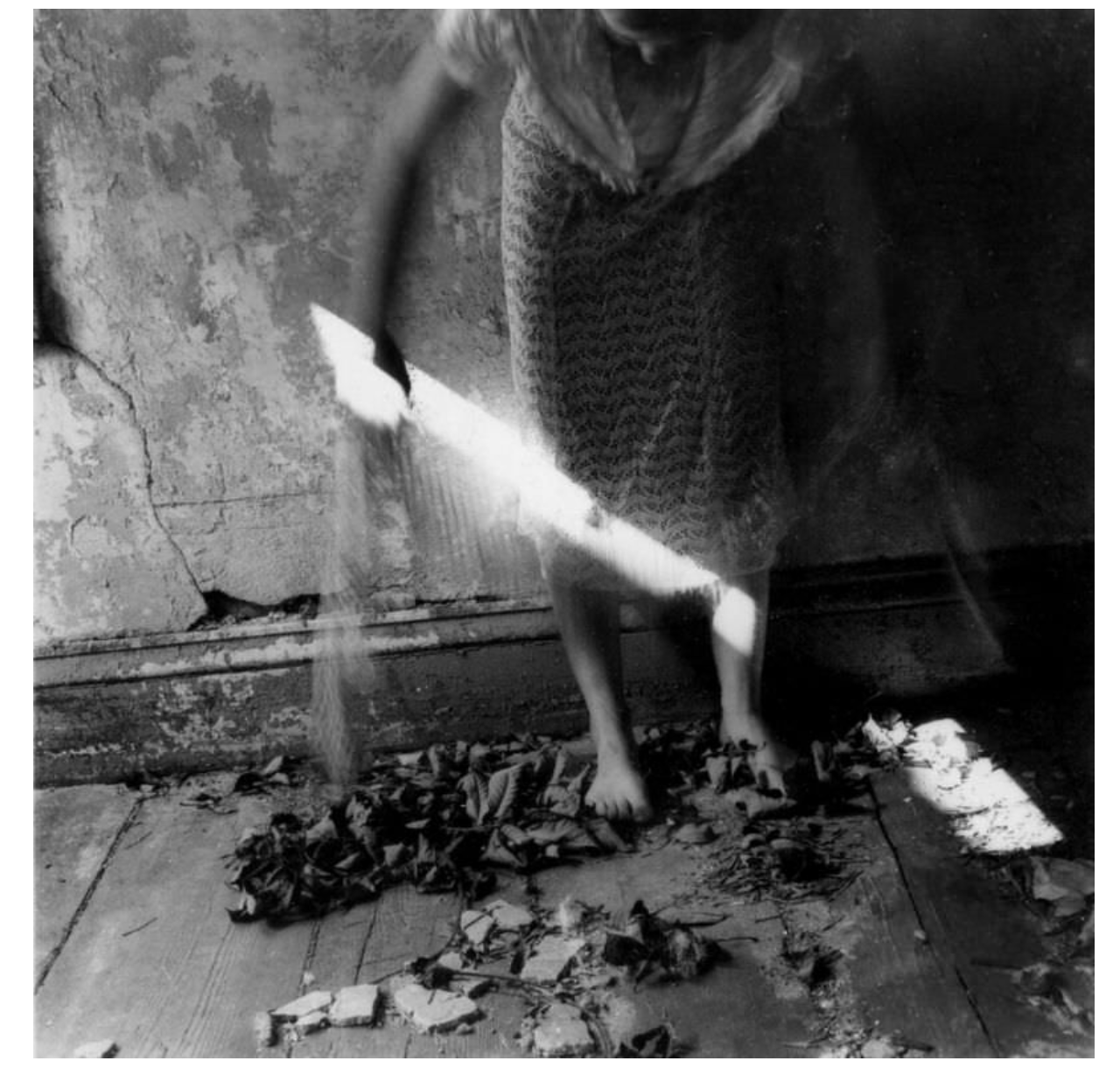

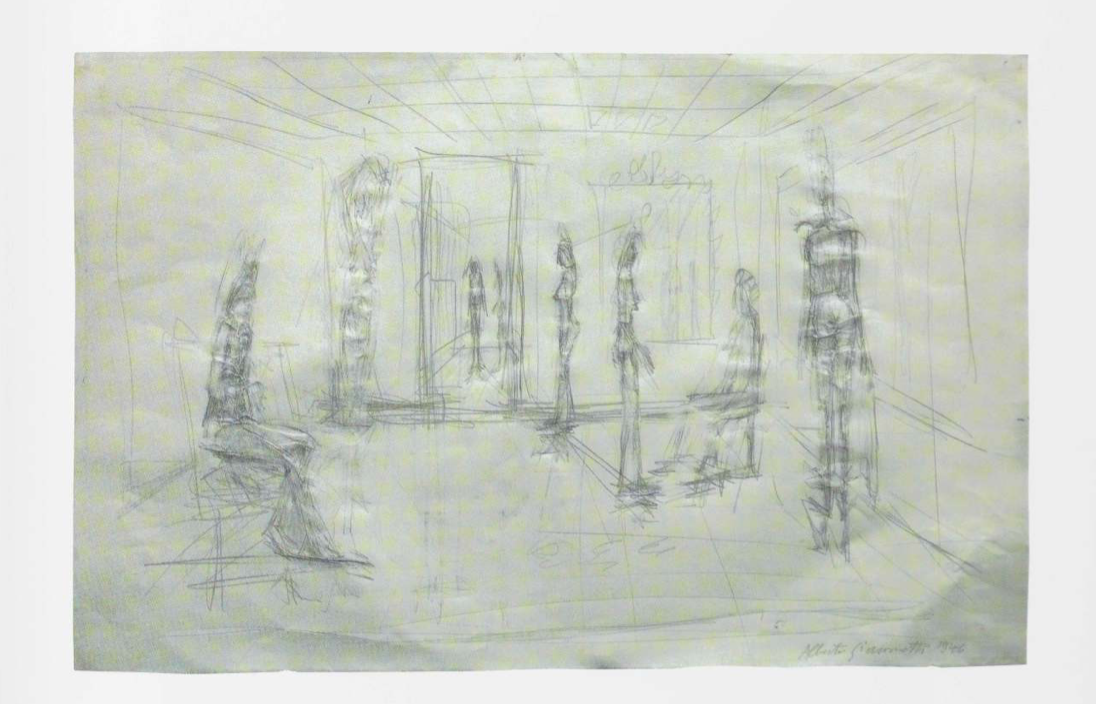

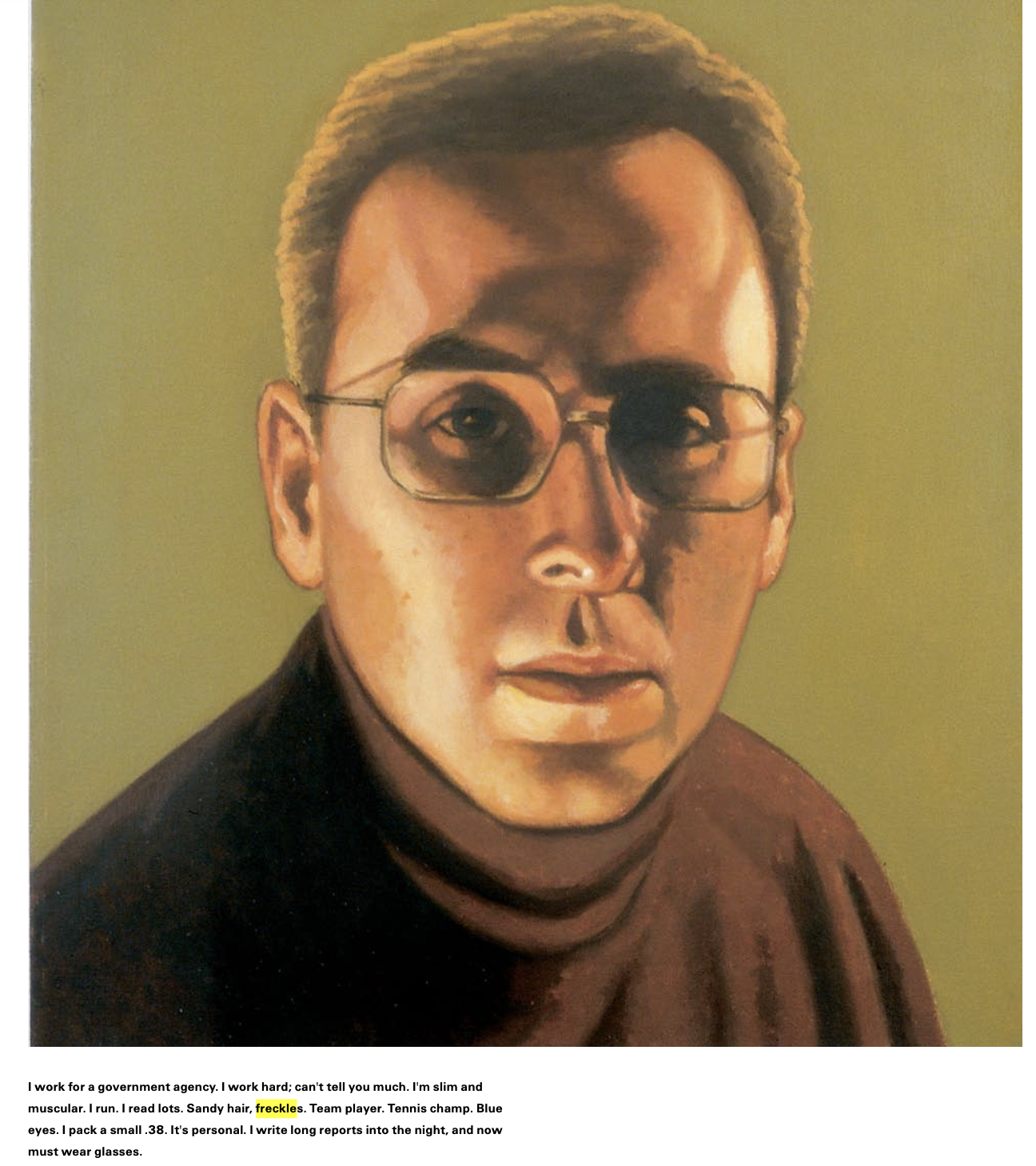

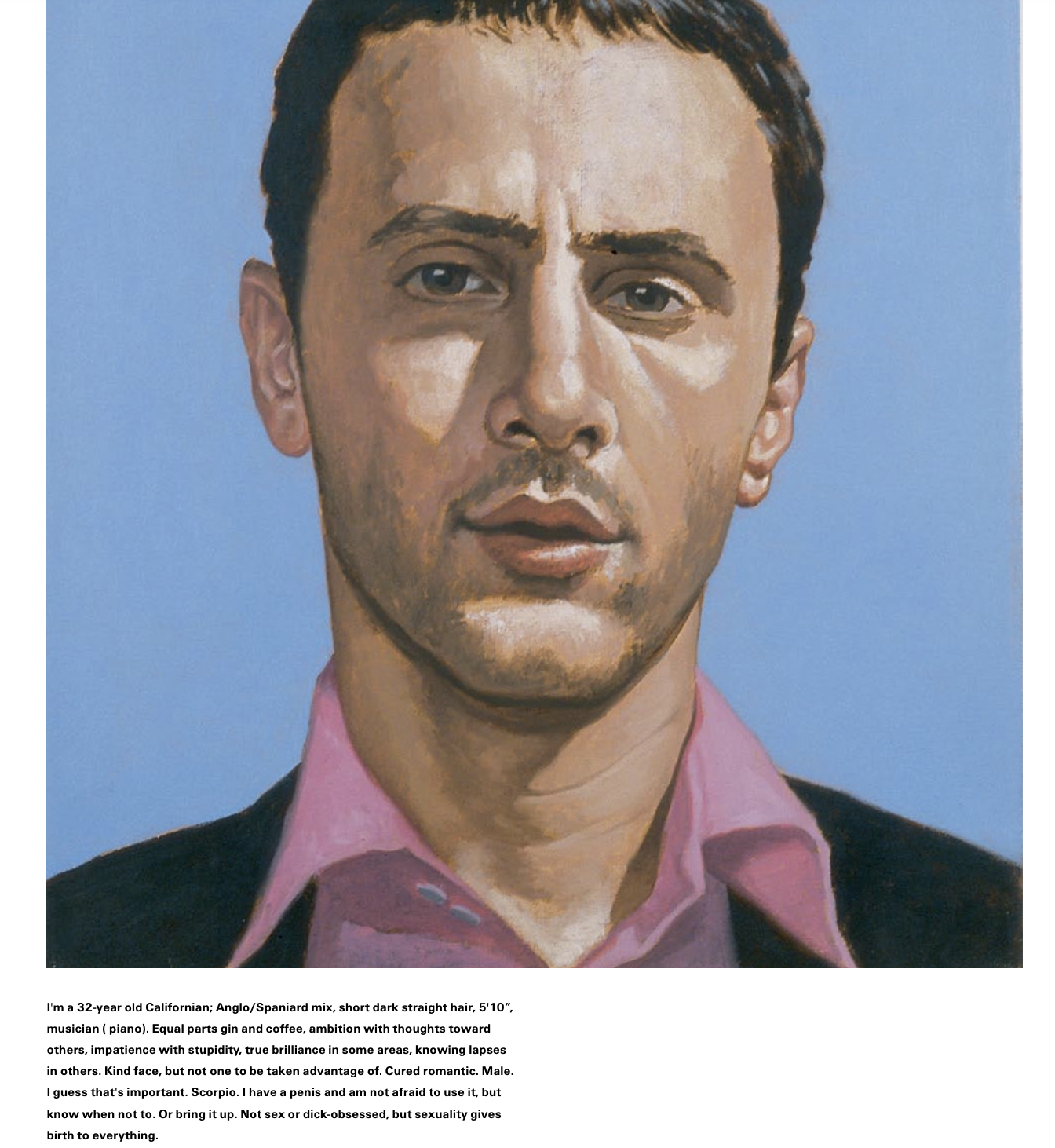

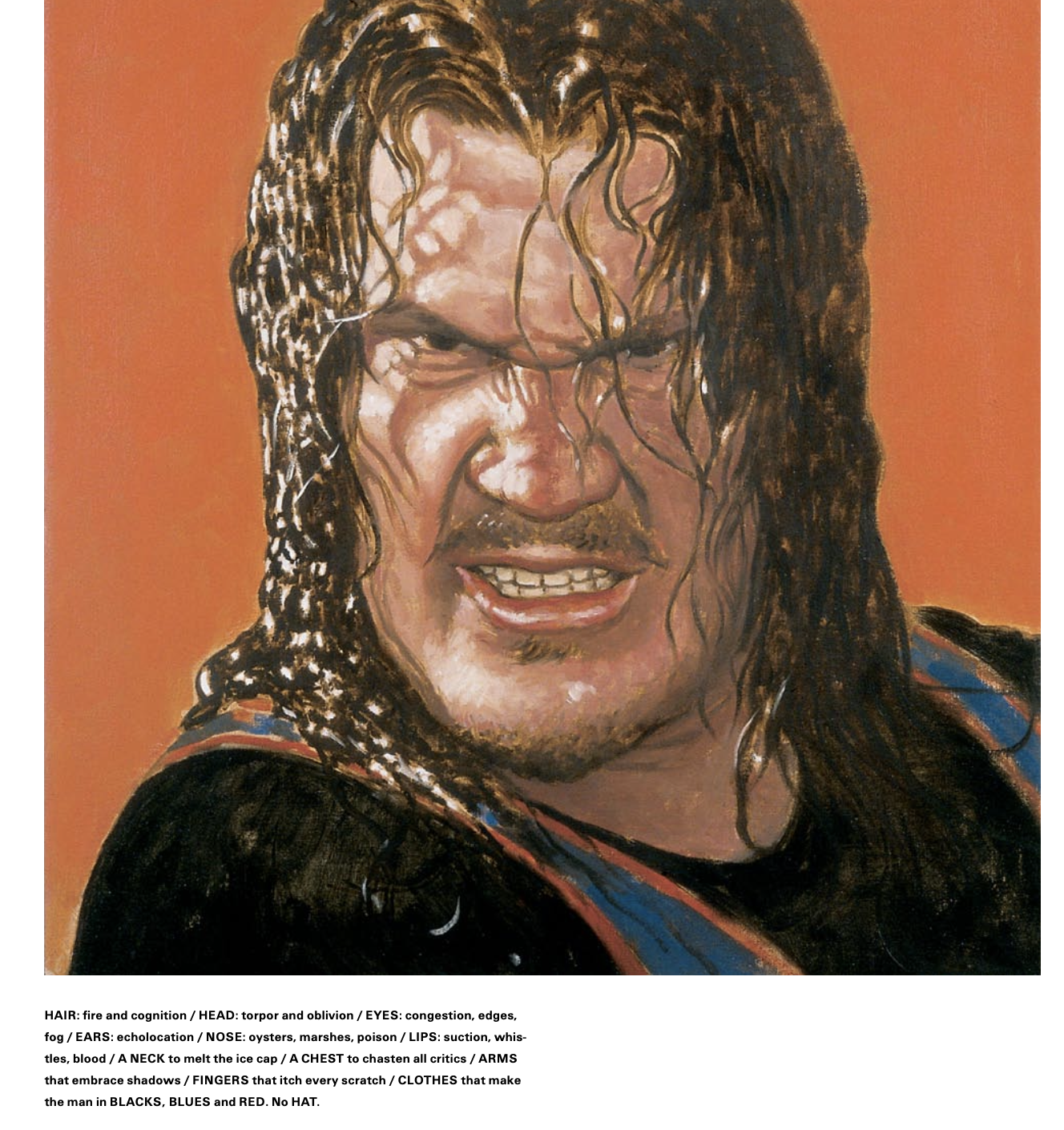

And few interesting pieces from The Cabinet, as assembled in “The Portrait Connection” feature from Issue 5. One could argue that these portraits are only interesting because of the role played by the captions in articulating their features and dynamics. The textuality of image is thrilling to consider and think around.

9

10

NATALIE GOLDBERG: Life is not abstract. It is not good or bad. It is. A girl is not pretty. Our mind makes that judgement. The girl has red lips, white teeth, freckles brushed across her nose, eyes that hint at lilacs, and she just lifted her right eyebrow. The reader steps away and says she is pretty. The writer just stays with the eyes, the lips, the chin, and makes no judgements.

RICHARD RUSSO: I’d been told before that writers had to have two identities: their real life one… and the one they become when they sit down to write. This second identity, I now saw, was fluid, as changeable as the weather, as unfixed as our emotions. As readers, we naturally expect novels to introduce us to a new cast of characters and dramatic events, but could it also be that the writer has to reinvent himself for the purpose of telling each new story?… And how is it remotely fair for Steinbeck to possess so many voices when I still didn’t have even one?

LUCY CORIN: The end reads as shock if you are the sort of person who can’t believe a couple of ordinary guys would do such a thing. But if you are the sort of person who does think a consumerist culture that leaves people with no idea what to do with their imaginations is not just a bummer but is dehumanizing and violent—well, then what is surprising is not that the guys kill the girls—the surprise is that you are surprised when it happens. Maybe you are surprised because of what you expect from a story. Maybe you are surprised someone said it.

ALT-J: I want every other freckle.

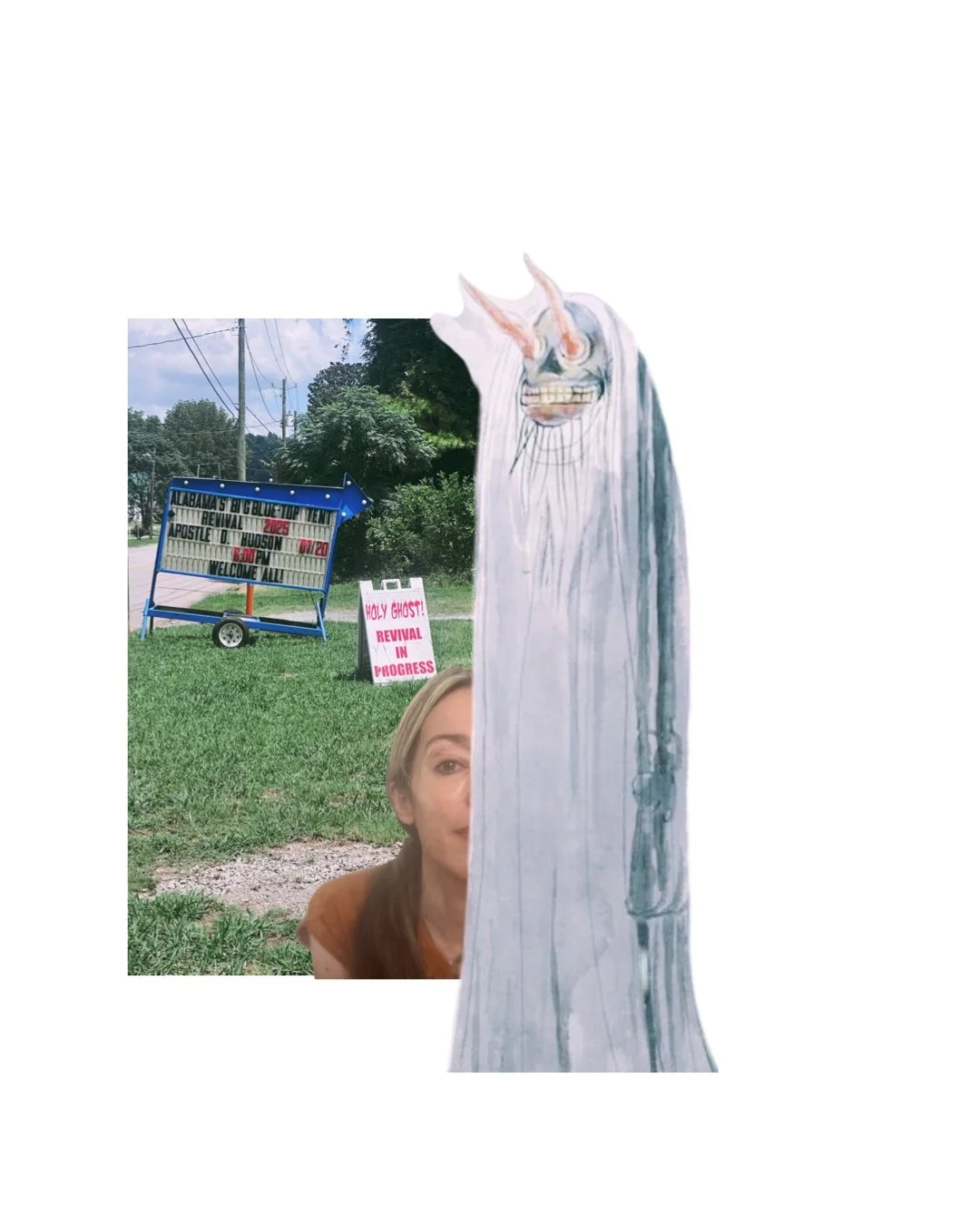

Alas, the tent was empty and the heat kept Alabamians from attending the revival. Sometimes the ghosts we create — the ghosts of our petroleum-fueled lifestyles and commodity culture— prevent us from meeting the ghosts we seek. Hauntology’s emphasis on the otherwise and the contingent isn’t simply material but also implicated in what we believe possible. What we dare to hope for or imagine. Not even our gods can meet us in the blazing heat of genocidal economies and obsessive boundary-policing.