|||||

Paris, 1963.

Roland Barthes introduces his friends to each other: Michel Foucault, meet Pierre Klossowski . . . both of you have a thing for Nietszche's eternal return.

The friendship between Barthes and Klossowski dates back to the late 1940s, when Barthes would visit K’s apartment on the rue Canivet to play four-handed piano duets with Denise, the muse of Klossowski’s life.

By 1947, his muse was his wife. Denise Marie Roberte Morin Sinclaire, a war widow who had been deported to Ravensbrück for working in the French Resistance, became Mrs. Klossowski. Abandoning his dreams of becoming an ascetic holy fool, Klossowski discovered a new vocation, both figuratively and literally, in art and literature—a fidelity to Denise’s beauty and body that would consume him until death.

One wouldn’t be wrong to say Denise dominated her husband, if one takes domination to include a certain seductive levity and recklessness, a lack of concern for bourgeois norms; a way of being at home in one’s body can diminish the need to be at home in the cosmos. Denise had a certainty that Pierre lacked. She wasn’t a seeker: she didn’t need as much from meaning as Pierre.

|||||

Paris, 1905.

Pierre Klossowski is born into an an aristocratic family of Polish émigrés. Even then, in the German-French bilingualism of his birth, the story of his life depends on the angle on the exposure and the role its shadows are given. Is the shadow or a speaker or a reflection of the body it follows?

was raised in an aristocratic family of Polish émigrés. His younger brother, Balthasar Klossowski de Rola, is more commonly known as the painter Balthus. Raised in France and Germany, thoroughly bilingual, good fortune lubricated Klossowski’s path by facilitating his social connections to influentials artists, including Gertrude Stein, Bataille, Masson, Walter Benjamin, Claude Mauriac, Roland Barthes, Rilke, Andre Gide, among others. He was, so to speak, in the right place (or class status) at the right time.

After his parents separated, Klossowski’s mother began an extended, intimate relationship with poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who became a sort of mentor to the young Klossowski. According to Benjamin Ivry:

Klossowski was still a teenager in 1923 when his mother Baladine's lover, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, introduced him to Andre Gide, a celebrated pedophile. Gide quickly persuaded Klossowski to send him pornographic stories and drawings about gay sexual adventures, to the point where the promiscuous Pierre found himself running out of true accounts and had to invent material to please the insatiable older man. In exchange, Gide introduced him to literary personalities of the day, including Jean Paulhan. An especially important friendship was established with Bataille, whose own works allied transgression, eros, and death in a highly Sadeian way.

Later, Klossowski worked as a private secretary for Andre Gide, a position that enabled him to read early drafts of The Counterfeiters as copyeditor. Gide had used the novel to chronicle his own journey into subjectivity, his discovery of the “I” through sexual experimentation and pleasure-seeking. The young Klossowski sketched a portrait of his mentor, Gide, in graphite pencil— an elder, bifocaled man sits at a desk with a small pile of papers crumpled beneath his hands as an androgynous nude youth plays a flute to his left. Narrowed into slits, Gide’s eyes seem to simultaneously see and imagine the naked youth with the flute.

He never settled on a medium or a path—-though he sampled many and sought spiritual reprieve or salvation from religion and art. “The redemptive theological potential of sexually transgressive art”—- this is how he phrased it to himself, in theorizing what he borrowed from Gide’s struggles. (Notably, Gide’s effort to make queerness spiritually palatable would lead him locate tragressive sexuality in the plan of a God he didn’t want to relinquish. It was an awkward, unqueering fit.)

In the years immediately preceding World War II, Klossowski wandered between monastic communities for three months before abandoning the habit for literature. His first novel, La Vocation suspendue ("The Suspended Vocation"), was published in 1949. Titled after the little-known book at the heart of Klossowski's novel, the “suspended vocation” is a story of lost faith, or the distance between a faith that has been lost and a faith that does not exist.

Denise is the Roberte of Klossowski's drawings and novels. Denise is one who led his hand to the large-scale drawing graphite and color-pencil sketches executed painstakingly on paper.

Marquis de Sade’s horrific universe, to Klossowski, was a paradox which evidenced the presence of a divine goodness. Klossowki, Foucault, and Blanchot bonded over their mutual fascination with Sade.

||||||

Roberte ce soire (1954) was haunted by its own desires from the outset. Rumors that Klossowki had portraited his wife for a porno-novel began circulating.

Jérôme Lindon, Klossowski’s publisher, tried to get ahead of the censors by packaging it as an art book with illustrations by Balthus in a deluxe limited edition. But Klossowski was dissatisfied with Balthus’ drawings—they missed the point of the book, they didn’t represent Roberte, they inserted his brother’s style into a book which challenged it, etc. Finally, a weary Balthus told his brother he should illustrate it himself.

And so Klossowski picked up his colored pencils and sketched the novel’s iconic moments, creating an iconography of carnality that can be observed from the edge of sanctity, as a Catholic might pause before each station of the cross when meditating on the Passion.

“The long-suffering, though apparently serene Roberte, her skirt unaccountably ablaze, is swiftly undressed by a mysterious male figure. Octave encourages the subsequent attacks on his wife, somehow convinced that these dramatic interludes will reveal to him her spiritual essence.”

- Brian Dillon, “In the Realm of the Senses”

Klossowski’s novel aimed toward establishing an erotic theatre of the heart through repetitions and Sadean ritualism. In some ways, the book wears blinders that protect it from its own idiosyncrasies. Extraordinary emotional sadism guised as generosity is one such blinding.

The book’s patriarch, an elderly cleric named Octave, emerges as a paterfamilias. Unable to fix the world, Octave is determined to rule by generosity in his own household. The “rule of hospitality” gives any visitor or guest the opportunity to make sexual use of Roberte, his wife.

Antoine, the nephew, is simultaneously disgusted and entertained by the strange sexual arrangements and conversations generated by the rule of hospitality in his uncle’s house.

The word “rule” creates meaningful tension in the novel. As a noun, “rule” refers to:

one of a set of explicit or understood regulations or principles governing conduct within a particular activity or sphere. (i.e. "the rules of the game were understood")

control of, or dominion over, an area or people (i.e. “the revolt ended Russian imperialist rule”)

In its verb form, “rule” projects power and establishes hierarchy; it designates whose word makes the law, and what this law covers. To rule is to:

exercise ultimate power or authority over an area and its people (i.e. “the legislative process of American democracy is ruled by corporations”)

prounounce authoritatively and legally to be the case. (i.e. “Octave ruled that the rule of generosity would govern his home.”)

The rule of hospitality is simply the rule of Octave’s property in his wife—-for only someone who owns a body can lend it. And only someone who is owned by another can be lended or shared or made available as an act of graciousness or virtue.

Roberte’s uncanny physical resemblance to Klossowski’s wife is not a coincidence—Denise is Roberte — and the name, or the act of naming, is critical to Klossowski’s view of fiction and language, to quote:

Fascinated by the name Roberte as a sign, while I was in the garden seeing nothing more of the sunny greenery around me having no other vision than the unstable penumbra in which the glow of her ungloved hand played – I resolved to describe what might happen in the penumbra, which was illusory. In the name Roberte I referred all that I saw, which I would not have been able to see without this name.

||||||||||||

In The Lives of Michel Foucault, David Macey spares no ink in outlining Klossowski’s influence on his subject. “Klossowski's novels and drawings make up an imaginary world in which erotic, religious and philosophical themes merge, and, being a self-confessed monomaniac, he has little interest in anything outside that world,” Macey writes, using monomania as the tiny trampoline which bounces him into a defense of Klossowski’s esoterica:

Although his work — and especially the trilogy known as Les Lois de l'hospitalité — is sometimes dismissed as misogynist and even pornographic, he insists that it has a mystical content and belongs to a gnostic tradition. Maurice Blanchot endorsed Klossowski's claims when he described his writings as "a mixture of erotic austerity and theological debauchery".

Both the novels and the drawings are sequences of scenes, understood in the theatrical sense of that term, and of humiliating encounters between Roberte and characters from a threatening commedia dell'arte. Roberte becomes an object of exchange, circulating endlessly in an erotic economy. She is raped and assaulted, is seduced and seduces, and takes on many different identities but remains unpossessed, inviolable, it being the author's conviction that the deepest level of individuality is a core which is both non-communicable and non-exchangeable. Like the tableaux vivants imagined and staged by de Sade's libertines, Klossowski's words and images betray an obsession with representation itself: representations of plays, of drawings, of drawings of scenes from plays, books about books. They are a theater of simulacra in which everything is represented, and nothing is real. The theatrical scenes that make up the trilogy, in particular, originated in planned drawings that were not actually executed.

In “In the Realm of the Senses,” Brian Dillon looked closely at the various poses in Klossowski’s work:

Klossowski once finished a series of drawings with the signature Pierre, le maladroit (Pierre the clumsy). In an artistic career that spanned half a century he could not really be said to have honed his technique. Rather, he worked tirelessly on the elaboration of certain obsessions, notably the insertion of the face and body of his wife, Denise - the model for the extravagantly ravished Roberte - into an apparently unending succession of erotic tableaux. The drawings are resolutely awkward. Their solecisms of scale and proportion are not so much evidence of formal naivety as invitations to address something that is, for Klossowski, far more pressing: the realm of gesture.

Time and again, whatever the prodigiously imagined scenario into which the artist has thrust her, Roberte adopts the same pose. Everything in these drawings, which expose her to grips and gazes, either malign or merely curious (as in the many images where she is seized by small boys), is actually in the arrangement of her hands. Whether beset by the sinister guardsman in Roberte ce soir, pawed and pored over by adolescents or cast in further fictionalized settings (the classical rape of Lucretia by Tarquin, the strange arrival of Jonathan Swift's diminutive Gulliver at the end of her bed), Roberte holds one hand close and closed, the other raised and open. Often her raised hand shields the eyes of her attacker while the other is thrust between her legs (the cue for questionable conjectures by Klossowski's narrators as to whether she is protecting herself or guiding her assailant). But the pose is not always a response to violence; it is to be seen too in the drawings of Roberte (or Denise) alone. One hand curled, the other splayed, Roberte, as the title of one drawing has it, is 'mad about her body'.

This pose has venerable antecedents. It is there, for example, in Raphael's The School of Athens (1510-11), in which Aristotle appears with one hand open to the world and the other on his Ethics. In the 'pantomime of spirits' performed across the ceaselessly replicated stage of Klossowski's art these twin gestures denote nothing less than the theatricalization of thought. Roberte, it turns out, is the true philosopher, not the desiccated Octave. Her limbs mime the attitude of a body and mind suspended between the spiritual and the carnal: 'the gesture of a silent physiognomy frozen in its expression: of denial? Confession? Or both at the same time?' Consistently, too, her face seems utterly detached from the fate of her body, casting slyly amused and sidelong glances out of the frame. In the end, says Klossowski, Roberte triumphs: in contrast to the Sadean extremes of torture visited on the adolescent female form, Roberte's body is transformed into a kind of pure spiritual drama whose final act is the assertion of her philosophical, moral and physical maturity.

“The penumbra, the glow of her epidermis, the glove, these are so many designations not of things existing here within my reach, but forming a set in conformity with the unreal penumbra …”

- Pierre Klossowski, Roberte ce soire

The speaker troubles the line between representation and imagination, or publicity and private fantasy, by interrogating his own intentions. Is it malicious? Is it epiphanic? Octave reads himself into the helplessness of the prophet who has been called by something greater outside himself to do the unthinkable:

“Will I still claim that it is not “representation” and that thought belongs to itself alone, not as my faculty, but as an intensity that found me here, in the middle of the greenery?… Will I say it is not I who designate what I understand by penumbra but thought, outside of me, which sees itself in the terms penumbra, epidermis, glove, etc.?

But haven’t I said that the sign’s malice consisted in answering, as name, to a physiognomy exterior to the sign?

Is it unthinkable if he takes pleasure from thinking it? I find myself thinking about close reading in these circumstances. I find the unthinkable as an aesthetic direction which rides the fabric shared by the sacred and the profane.

Klossowski’s sign projects a shadow onto “the reality of the world,” and this shadow covers the physical features and body “exterior to the sign that it dissumulated under this name.” The problem is that perfect overlap doesn’t explain the shadow, the part of Roberte he can’t know without imagining. He is, in his own words:

. . . unable to limit myself to the simple coincidence of the name with this physiognomy seeking instead an equivalent to this coincidence, under the constraint the sign exercised over me, yet seeking the sort of equivalent as much to escape my madness as its constraint, though not being able to keep myself to the shadow of the sign…

From the moment I set myself to describing this very physiognomy in the notation of the utterances flowing, outside of time, from the name Roberte, and from the moment that, in these discontinuous facts, it figured, no longer by its mere coincidence with the name, but as physiognomy, which until then was exterior to the sign that had covered it over with its shadow, the description of the shadow itself came to establish the contours of the physiognomy as its participation in external reality, and this physiognomy emerged as if from itself from the shadow spread over reality by the sign….

The “laws of hospitality” that fascinated the Foucault of later years appears in Klossowski’s early portraits of Roberte, particularly in the relationship between the name and the sign (in a passage that reminds me of the passage on naming in Kate Briggs’ latest):

What did the silence of this physiognomy opposed to its name as sign amount to? Was the sign to be taken as a portrait? Wasn’t it the model, since it had become this sign?… Instead of the equivalent to the madness I had avoided, I found between the silence of the physiognomy and the silence of the appreciation of the outside, a portrait. But since it was still a question of juggling the unique sign, I wanted to exploit this silence of the portrait to make a painting… Then, this portrait, suddenly peopled with other figures, became a painting destined to teach through its image. But the lesson taught by the image is only the institution of a custom: the laws of hospitality.

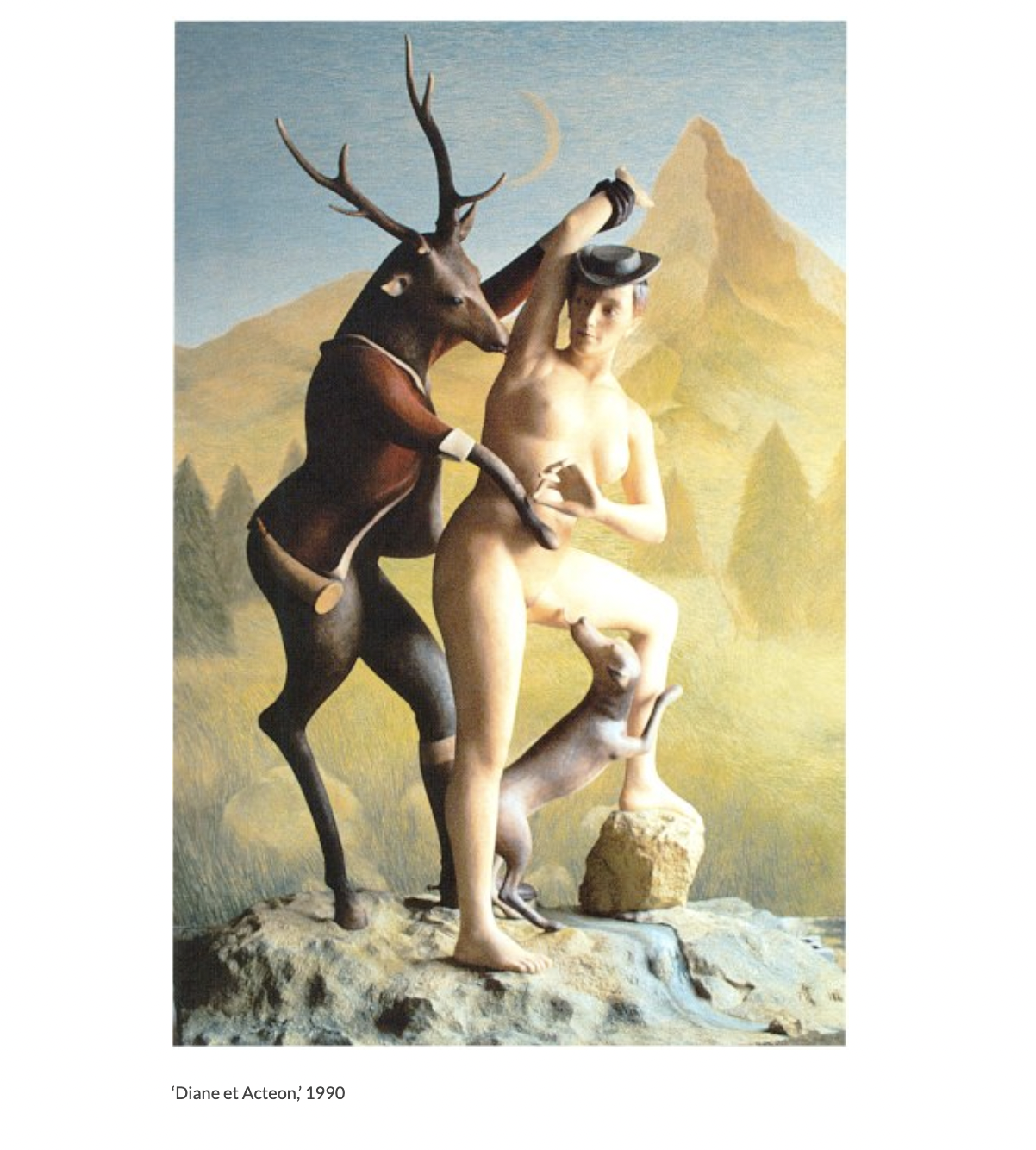

Foucault was particularly interested in Klossowski's Le Bain de Diane (1956), a series of drawings that pivot around the myth of Diana and Actaeon. He described it as a "text dedicated to the interpretation of a far-away legend and a myth of distance (a man punished for having to approach the naked divinity)... Diana reduplicated her own desire, Actaeon metamorphosed both by his desire and by that of Diana."

||||||

Paris, 1935.

Klossowski meets Walter Benjamin. More than three decades later, Klossowski will describe this encounter retrospectively, in a 1969 essay for Le Monde titled “Entre Marx et Fourier”:

I met Walter Benjamin during one of the meetings of Contre-Attaque—the name of the ephemeral fusion of groups headed by Andre Breton and Georges Bataille, in 1935. Later he assiduously attended the College of Sociology, an emanation intended to make “exoteric” the closed and secret group Acephale (crystallized around Bataille, following his rupture with Breton). From this point on he was sometimes present at our secret meetings.

Disconcerted by the ambiguity of “acephalean” a-theology, Walter Benjamin disagreed with us, arguing that the conclusions he then was drawing from his analysis of German bourgeois intellectual evolution, namely, that the “increasing metaphysical and political buildup of what was incommunicable” (according to the antinomies of capitalist industrial society) was what prepared the favorable ground for nazism. For the time being he was trying to apply his analysis to our own situation. He wanted to keep us from slipping; despite an appearance of absolute incompatibility we were taking the risk of playing into the hands of a “prefascist aestheticism .” He clung to this interpretative scheme, thoroughly colored by Lukacs’s theories, in order to surmount his own confusion and sought to enclose us in this kind of dilemma.

There was no possible agreement about this point of his analysis, whose pre suppositions did not coincide at all with the basic ideas and past history of the groups formed successively by Breton and Bataille, especially Acephale. On the other hand, we questioned him even more insistently about what we sensed was his most authentic basis, namely, his personal version of a “phalansterian” revival. Sometimes he talked about it to us as if it were something “esoteric”, simultaneously “erotic and artisanal”, underlying his explicit Marxist conceptions . Having the means of production in common would permit substituting for the abolished social classes a redistribution of society into affective classes. A freed industrial production, instead of mastering affectivity, would expand its forms and organize its exchanges, in the sense that work would be in collusion with lust, and cease to be the other, punitive, side of the coin.

Paris, 1937.

Walter Benjamin follows the Moscow trials in shock. Dennis Hollier describes Benjamin’s silence as a sort of “political aphasia”. In a letter dated 9 July 1937, Benjamin tells Fritz Lieb that “the destructive effect of the events in Russia, […] will necessarily continue to spread”:

What is sobering about this is not the hasty indignation, of unshakeable combatants for ‘freedom of thought’ what seems to me far sadder, and at the same time far more necessary, is the silence of those who think, who, precisely because they think, have a hard time considering themselves as people who know. That is my case.

Paris, 1938.

In the days prior to the Munich Crisis, Georges Bataille sat in Paris and penned a letter to Michel and Zette Leiris:

“I only have this to add: whatever one could say about any other subject wouldn’t be any more cheerful. I like to hope that you don’t read the newspapers (this exercise has never been more futile): the only serious and informed people that I have seen say that all the reasoning and all the interpretation are absurd, that we have absolutely no way of knowing what may happen. I hope you are enjoying this bad September without a care.”

Bataille’s gesturing towards silence will match that of Blanchot. Once the German occupation of France begins, Bataille will maintain this silence throughout, with the “we have absolutely no way of knowing what may happen” becoming a thread in the writing of the disaster. Or the silences of Edmond Jabes’ deserts.

In the early 1970's, Foucault's politics led to the icing-over of his friendship with Klossowski. Although the friendship crumbled, David Macey insists that "it has its monuments”. Among them, this specular coincidence:

In the late 1980s, Klossowski found a moldering piece of canvas in Balthus's château and interpreted the patches of damp on it to create two versions of a drawing entitled “The Great Confinement II” (1988). Both include a portrait of Foucault; in the second version he is surrounded by portraits of Strindberg, Nietzsche, Bataille and an anonymous pope, while Freud, to Foucault's right, contemplates a sketch of Leonardo's “Madonna and Child with St. Anne”.

||||||

Birmingham, 2023.

Au fin: there is gratitude to saladofpearls for the quotations and thoroughly-sourced citations, and to Rainer J. Hanshe for his bibliography, and to Daniel W. Smith, for his decades of prodiguous scholarship and engagement of Klossowski’s work—for his diligent monomania.

As I was typing my notes earlier this week, goosebumps met me halfway between the shame of deadlines and the glee of discovering that Dennis Cooper blogged (extenstively) about Klossowski on August 23, 2003. Cooper mentions a special issue of Diacritics, edited by Ian James and Russell Ford, will be (or maybe was) dedicated to Klossowski. Lest monomania prove contagious, I will leave this vessel in order to board a more fashionable one and receive a paycheck (while apoologizing in advance for the gloss that leaves the K disconnected).