Wherein she attempts to dump a bit of her recent obsession with yellow onto a screen—-for you, whoever you are.

To begin with gratitude for other writers, particularly peers in poetry and music, who drew me deeper into this poem last night.

To begin with the shape of it—

The figure of the poem on the field; the way it occupies space.

Four stanzas of different length.

Or: three stanzas and an addendum; a trinity with a scrap left on the cutting floor of creation.

Or: a quintet, a sestet, a septet, and a monostich.

The decision to “grow” each stanza with an additional line is deliberate, and accumulative. I imagine Ruefle tarried a bit in the second stanza, trying to decide where to break for the last line. “For me” settles it, but not cleanly. It draws attention to the “me” in a way I’m not sure the poet intended, which is to say, I can’t know if she meant this. It makes a snapping sound, that break.

The title addresses an unknown interlocutor indirectly, speaking to the “tenor” of (his?) yes. The structure of the sentence tells us that “You” has affirmed something. If the poem is a painting, the title is the caption scribbled beneath it.

The leave-taking of the poem with that final line, that slim thread: “Much like god at the end.”

To stare at that “tenor” for a minute—

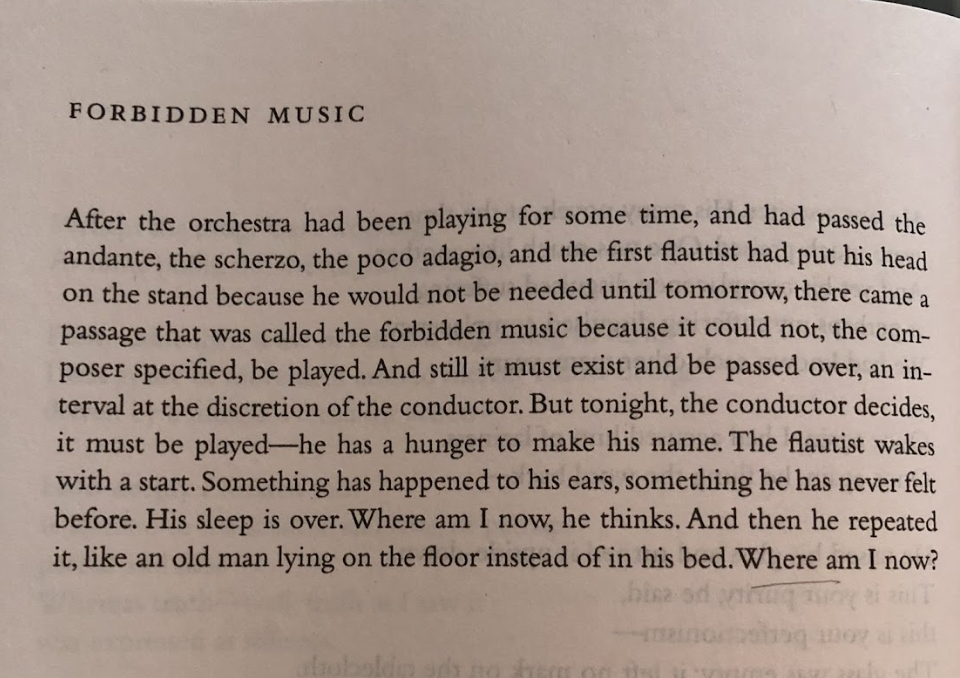

The titular word, tenor, is a noun that refers to:

a singing voice between baritone and alto or countertenor, the highest of the ordinary adult male range. A singer with a tenor voice. A part written for a tenor voice.

the course of thought or meaning that runs through something written or spoken; purport; drift. continuous course, progress, or movement.

These are the general uses of tenor, and Ruefle could be said to be playing into both of these meanings, rubbing the duplicity and uncertainty for valences.

But there is another definition of tenor that comes from finance, where tenor refers to “the length of time remaining before a financial contract expires.” This “tenor” is sometimes used interchangeably with “maturity.”

To return and discover two gestures—-

But first, something else: something that is not the figure but the saturation, the poem’s tonal qualities.

What is at stake for the poem? What the poem desires from existence?

Like us, the poem knows itself as an articulation of specific desires in relation to constraints. This tension drives the poem, or shapes its movement and tempo.

The first two stanzas begin in the conditional form. The acquire momentum through a matched construction of syntax:

If you were lonely

and you saw the earth

you’d think here is

the end of loneliness

and

If you were sad

and you saw the kitchen

you’d think here is

the end of sadness

and

The third line in both stanzas is identical, a repetition that isn’t quite a refrain, but does some of the formal work a refrain accomplishes. There is a mirroring motion, a play on possibility, an interest in what could-be the case.

And there are two gestures at play, gestures that may speak to the desiring.

In the third stanza, the poem’s speaker refers to a painting by Joseph William Turner, but she does so in a gesture that refuses proper naming. She gives us a shortened version of the name along with a referent: “Turner painted his own / sea monsters.”

We are given enough to find the painting, but not enough to define it. It is one thing to find and another to define and the order of operations may fall under the purview of epistemology.

First gesture: there is a painting . . .

Second gesture: there is something else . . .

Something else is the classic Ruefle ingredient, the elliptical metaphysical. She does not give us the title of the painting because giving us the title would denude the metaphysical gesture of the poem.

And yet the painting is central to the poem. I’m not certain this poem could exist without the painting.

The look at the painting—-

Turner’s Sunrise with Sea-Monsters (1845) was left unfinished.

It is so yellow. How strange that Ruefle’s poem doesn’t feel yellow. How odd that the dominant note of the Turner’s dawn isn’t elicited in the poem at all.

And we are speaking of sunrise— but the yellow is wan. The feeble yellow lacks a certain robustness. There is no fire in it. There is no orange warming the undertones. And I want to risk calling it weak, to risk expressing the absence of a forge-orange in this hue of yellow. It is not worthy of a Prometheus or a Promethean labor.

The effect is softening, like the whisper of pastel paint on a wall; it quiets and soothes me. If this yellow were a song, it would be soporific. A yellow lull. A hum. A lullaby is the song intended to settle the mind that has witnessed the chaos of creation.

The lullaby yellowing the melody—-and the song distinguished by diminishing, its fading out into slow diminuendo.

Diminishment is not dissimilar from incompleteness.

And the monstrosity—

According to the current description offered by Tate Museum:

This is one of Turner’s most mysterious unfinished paintings. The shapes of two or more giant fish can be seen against a yellow sunrise. Dark brown hatched lines to the left of the fish may suggest netting or fish scales. Turner would have read of sightings and stories of mysterious marine creatures by sailors engaged in Britain’s multiplying naval business interests. Despite its bright tonality, this work may relate to Turner’s frequent depictions of the sea as dark place.

Tate reads this painting in relation to the expansion of the British maritime empire, and the absence of the word “colonialism” hovers in the silences of the soft-pedaled historicist description. From this, we can assume that Turner’s painting draws on the thriving community of sailors and fishermen who hung out told stories (or "shanty tales"). Maybe the artist heard lore about sightings of mysterious marine creatures by the men who went out in the water. Tate’s description aligns with the spirit (if not the exact content) of Turner-expert James Hamilton’s reading. Hamilton wanders deeper into the mist and speculates that a paddleboat is being consumed by giant fish or whales inside it. The “steamboat theory” follows the interpretation of Turner's later work as a reflection on the technological changes of the Industrial Revolution.

Although this is a very specific, economic take, it is also conspicuously genteel in its elisions: no one mentions the exploitative nature of maritime economy. The absence of this mention makes it difficult to read Turner as critiquing the change. One wonders why bother with Big Steamboat energy at all—-and one wonders this because the role played by light, the lull of that yellow yellow yellow, feels significant. One might even say that the Sea Monsters of 2023 are unapologetically British in their affect?

The singular monster v. the many—-

What do I see? What can I be certain about in Turner’s painting?

There is the shape of a thing which seems to be fish, or which have fish-like heads. Maybe there is a red and white striped buoy present among the fish. Certainly, there are traces of interesting shapes in the lower right corner. One critic discerned a dog's head to the left of the monster. “A paper in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine draws a connection between these figures and Turner's possession of acetate of morphia (a drug related to morphine), possibly used for the treatment of a toothache” (Wikipedia).

In thinking of text and descriptions of art as translation, I am thinking with an idea shared on twitter yesterday:

Translation is a form of literature, a literary art. It does not (and *cannot*) replicate the original. It *creates* the poem in a different language. I treasure the sonic voluptuary in these five translations of Rimbaud by Christian Bok.

What is the difference between Turner’s painting and the museum’s textual narration of it? What is the distance?

In a similar vein, I tried to think about what Ruefle’s poem desires from the world, a question that inevitably touches on how one conceives existence? What does the poem risk in relation to that desire?

“If you were lonely / and you saw the earth / you’d think here is / the end of loneliness…”

The final monster—

The language-freak in me reads gallery/museum descriptions as textual relics that reflect the interests and concerns of their time. While the painting remains the same, the words used by humans to describe the painting flutter, bustle, shift. The temptation to take these descriptions as definitive is common to museum-goers.

But a poem that gestures towards metaphysical incompleteness cannot be pinned to a definitive reading. And an unfinished painting exists —-always—in relation to its unfinishedness.

Tate’s 1907 catalogue lists the title as Sunrise, with a Sea Monster. In 1907, there was one “sea monster with a head like a magnified red gurnet” and this sea monster was “floating on the misty waters” which reflected “a yellow sunrise.” In the “distance",” there were “forms suggesting huge icebergs.”

Drawing on Turner’s sketchbook, the Sea Monster of 1907 is related less to maritime trade than to the particular whaling expeditions Turner sketched. It is “as thought Turner was occupied at the time with the wonders of the deep waters related by Arctic voyagers.” The Sea Monster of 1907 resembles a “similar drawing” that hangs with his “exhibited watercolors.”

So much has changed in the interim. So much like god at the end.