"Music causes plethoras in the head."

— Soranus, 2nd century CE

I’d like to begin this reading with a note on pronunciation, and an appeal to unrelenting awkwardness of this Beckett-style moment in which You— the persons who live in this town whom I am visiting, persons who are possibly affiliated with the university from which I matriculated — have an expectation that I would be something pronounceable.

Expectations are based on sounds, which is to say language, words gathering together into small parcels of meaning. We gather to hear them. They gather to enable us to encounter each other. Words and humans gather in this uncertain, expansive relationship rooted in a persistent hope that something meaningful can be made of a moment, a view, a life. And so I am surprised tonight to discover something utterly human in me, namely, a melancholy. How sad that anyone would worry about whether they had pronounced my name correctly. How unfortunate that we should gather and be gathered with the fear of mispronunciation among us.

My father says Americans can't pronounce “Ceausescu” correctly because they don't do diphthongs. Their mouths aren't wired to holding so many vowels in one hut at once without cracking. So I have centered vowels in my poems—crammed and jammed them, making space for unassimilated voices. I am loyal to sounds, and a traitor to any part of the “self” we try to see whole.

This particular melancholy reminds me of an ongoing discussion with my youngest child— a problem that I find easier to express in a poem, with Tomaz Salamun's little horse in the future anterior.

[Poem: “I Have An Imaginary Pony”]

My daughter's pony is invisible, but my relationship to her pony is imaginary. I can only imagine what she has imagined to the point of invisibility. And invisibility, here, is the only way she can relate to the pony she cannot own.

We cannot know each other the way we crave to be known.

Ah-LEE-nah. Is it wonderful to hear my name pronounced correctly, wherein "correctly" is defined as the way it is pronounced in my native (and very minor) language? Does the thrill of hearing myself pronounced in my first language relate to the power to be one simple thing, one Alina Stefanescu, one constant and stable self? And is there—beneath that thrilling presumption, perhaps— a refusal to be known as one of you, as among you, in your presence, in your language —known as spoken and held in your mouth?

As a reader, it is not your job to acknowledge me, to affirm me, or even to perceive me correctly. I believe that such expectations set us up to fail in beholding one another. It is too much to ask of any human. I keep thinking of Beckett's Godot and the firmament, and the constant question that the two old friends, waiting, ask one another. The endless repetition: Who am I to you? Who will we be to one another?

To be read is one way of knowing. To be pronounced is another. To be remembered, well, to be remembered as both a blessing, and a curse in any language.

I cannot know myself in the phrasings or interactions that present me— and give me to you, in flashes and stanzas, tonight. To ask of the human the infinitude we hope from the poem is too much.

Earlier this week, I found myself returning to Michel Foucault, whom I first studied here on this campus decades ago. The Auburn Philosophy Department taught me to think, which is to say, Dr. J covered my papers in red ink – "What does this mean? No more flowers! What are you arguing?" I took every course I could with him, for the thrill of being challenged, for the gift of being taken seriously, worthy of criticism.

The funny thing about Foucault is that his most famous work in Madness & Civilization relies on an archival history depicting the Ship of the Fools, a boat that carried mad men around. But his peers dragged him through a journal for failing to source the ship of fools.

It seems that Foucault never actually replied with a credible archival source. The Ship of Fools existed, but did Foucault's ship of fools exist outside his book? This existential question is one of both philosophy and poetry. I found myself on his ship of fools earlier this month, and I wanted to share the first draft of it with you. To be unfinished somehow, and to risk reading the thing-in-creation.

[Poem: “So Foucault Failed to Source the Ship of Fools”]

Who were the mothers in that hospital room of bills that sink us all? Why do we punish the sick and suffering and vulnerable by making it impossibly costly to survive? I return again to Beckett's Godot, which I saw performed in a black box a few weeks ago, and how the first half of the play seems to tell us that only the burdens we carry give us reason to continue.

I don't know about that. Sometimes I look at other mothers and feel so close to them, even though they are strangers. What could be stranger than this overwhelming love we feel for our children? What could be weirder than the feeling of being subsumed and totally sunk by it?

[Poem: “The Mother Test No One Talks About”]

There's a lovely part among the countless leavetakings in Godot, in the parting scene where the friends shout out "Adieu" again and again, making a refrain of a word in the language that Beckett adopted as his own, namely French. Adieu means goodbye in French but it also could mean to God. Derrida’s notion of leave-taking returns to this ‘a dieu’ that honors the life which can no longer defend itself.

I’m afraid we have very little respect for the dead in the US, and this is legible in the mainstream disregard for poetry and literary forms that bind us to eternity.

I'm not sure what any god means or wants. Certainly, they have demanded a lot of blood from our species over the centuries. The gods do not strike me as good poets, even if many of the humans who love them are.

Speaking of love, I met the man who became my husband in Virginia. I also left the man who became my husband at least 7 times before agreeing to marry him, and then actually following through with it. Adieu, I said to him. Adieu adieu adieu! Sixteen years later, with three kids and a terrible, wonderful schnauzer named Radu between us, I remain amused by how utterly different we are— his Kierkegaard to my strange mix of French continentals and Wittgenstein.

Here is a poem for him, who is doing the caregiving this week. About how we coexist as strangers to another. How strangeness keeps us interested.

[Poem: “Separate Bumper Stickers”]

Speaking of strangers, we feel as if we know them— we have seen them before—but we don’t re-cognize them. We know the stranger even though we can’t recognize the stranger.

The awkward silences are gifts. Silence is terrain studded by landmines: blank, ambiguous terrain which intends to avoid stepping into harm. Yet this approach anchored in avoidance changes the terrain by rendering it dangerous in an unspeakable way. I remember listening to a museum guide describe the avalanche that destroyed a small town in Colorado as a mystery. "It is a mystery," she insisted, when pushed for information.

All mysteries lean into their silences, the patched secrets which active mining communities keep in order to survive. The words that surround silence are like the signs labeled NO TRESPASSING; they signify the requirements of keeping distance while also challenging us to find a reason.

Perhaps my obsession with sign-reading is tied to my childhood, or to being the child of Eastern Bloc refugees raised in the American South which is to say: I recognize a barbed silence when I hear it. Recognition commits me less to knowledge than to asking, studying, wondering, chasing. The writer who rejects a borders' imposition of "peace and quiet," the poet familiar with ontological complicity — cannot leave a silence unchallenged. The words with false bottoms demand my attention. What is this expression trying to hide? And what is this silence denying?

The silences in my recent poetry collection are related to Ceausescu's dictatorship, and the things my parents could not say. The cost that their “defecting” posed to their family in Romania.

[Read from Dor]

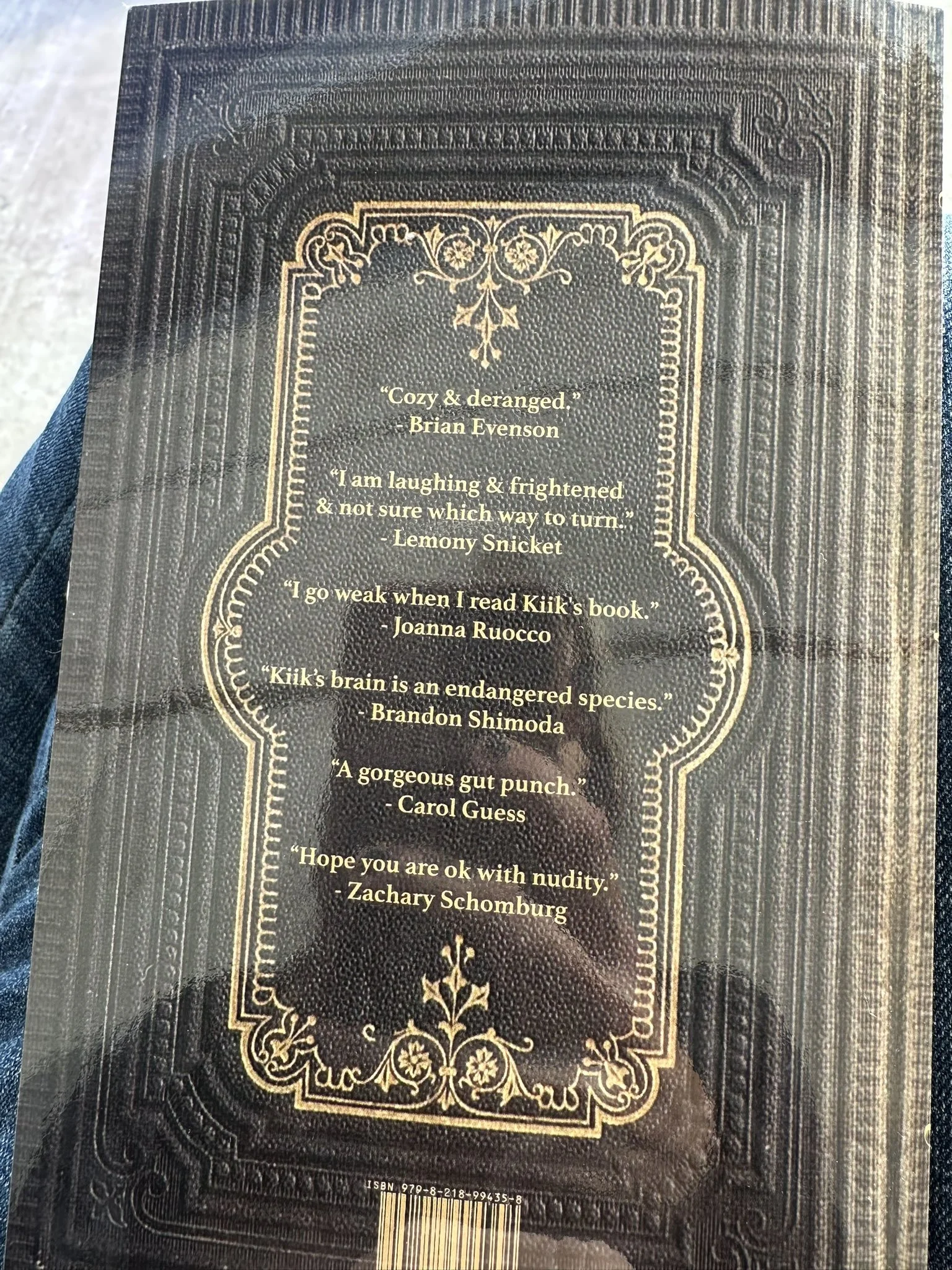

Dor, this book, is about a word I wanted to bring over borders— a Romanian word that means so many different things to different people. “Dor” is often compared to saudade as a form of nostalgia. We lost interest in that ancient word until it became a medical diagnosis made by Swiss Dr Johannes Hofer in 1688. Hofer applied this diagnosis to students, noting that nostalgia created false representations which caused the nostalgic to lose contact with the present, to stop caring. In a sense. But “in a sense” is still only one sense of the matter. (Just as “innocence” is a lie in any discourse including humans with American passports.) There are more senses than the sense implied by the argument.

Obsessed by a longing for their native land, Hofer's nostalgics experienced something like homesickness. Hofer's sense still dominates the discourses of nostalgia, the shame of looking backward, the punishment of turning to salt. How interesting that this sense of nostalgia implies a home.

Reading John of the Cross, I wonder what "home" means to a monk. I wonder if one who has cut so many bonds with the physical, sensual world can experience a "rooted" longing. It must just be god. The ashes of my book's first draft sit in a box on the shelf to the left of my mother's ashes. The poem permits my mother to read the book which appeared after her death.

[Read two from Dor, including lustration]

In sum, I do not want to be known in the way that pronouncing my name in Romanian would have me be known. I want to be known as I am, right here, in this encounter with You—where you are a poem, too. And what your mouth does with me. I want that.

I want the ‘me’ that emerges from this, from us, from now. My “I” cannot speak for an other. It cannot and does not. I speak for no country, no community, no flag, no god, no guru, no nation. But there is a world in which we can articulate our impossible hopes aloud, and that world happens to exist above the borders of nation-states, somewhere in the republic of letters as dreamt by poets and writers. There—-and here— and now— I want to be known in the way you imagine my name sounding, in the ambiguous and complicated uncertainty of humans beholding one another— acknowledging our inherent strangeness in this moment of relating, committing to the radiance of that— and—-accepting, perhaps, that the stranger is also one who wishes to be recognized rather than known. Surely, we cannot ever entirely know the difference.