An excerpt from Bruno Schulz’s “The Republic of Dreams”:

And here is a PDF of the “The Republic of Dreams” in its entirety— with a bit of annotation.

Map of Galacia, 1910.

An excerpt from Bruno Schulz’s “The Republic of Dreams”:

And here is a PDF of the “The Republic of Dreams” in its entirety— with a bit of annotation.

The Henryk Sienkiewicza school in Drohobycz, where Jozefina was working from 1930-1934, when Bruno Schulz met her. The building is currently a private residence.

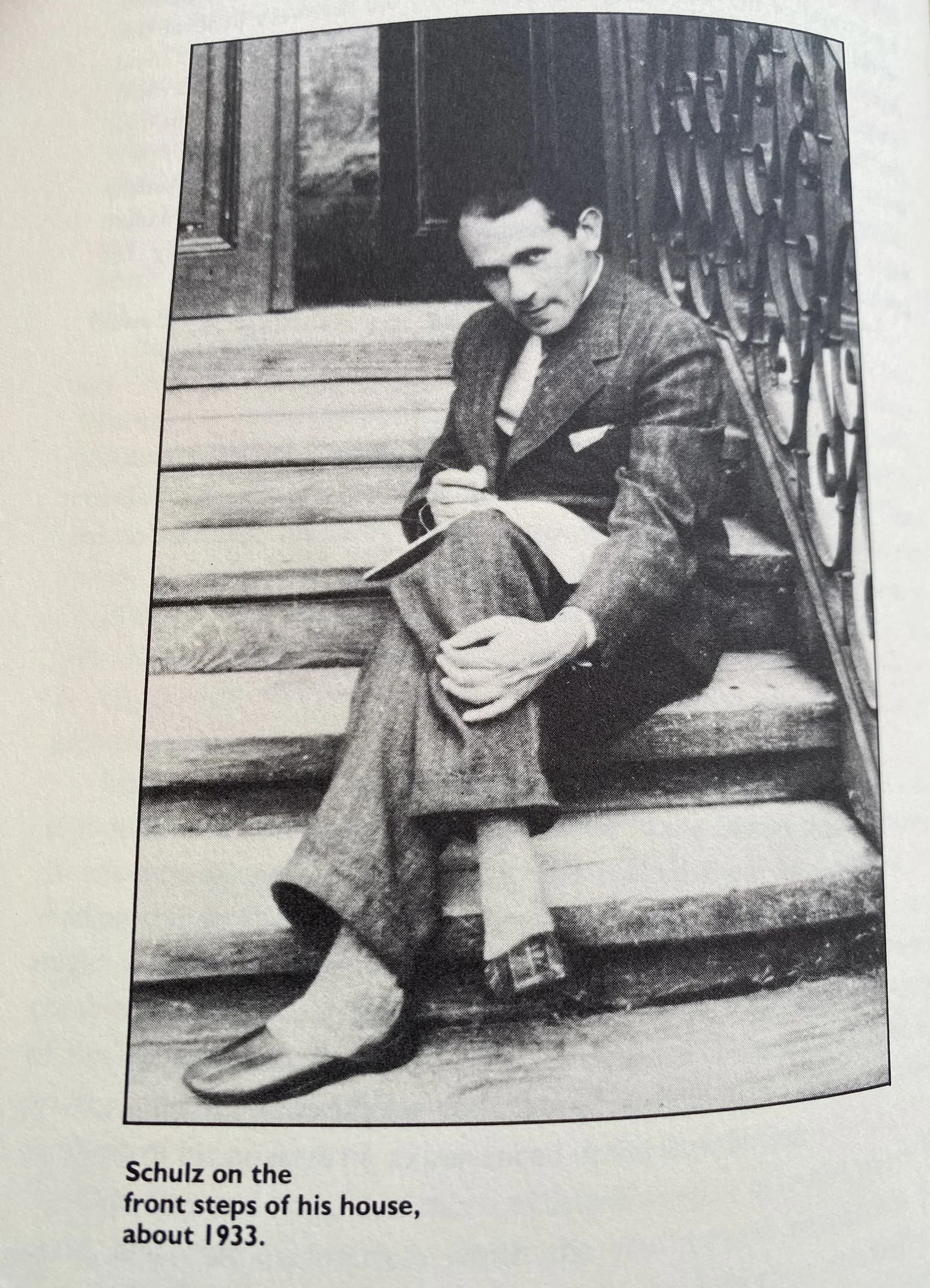

Spring came early in that year of 1933, when Bruno found himself fascinated by a 28 year old teacher at the local seminary. Her name was Józefina Szelińska—and she was equally fascinated. She agreed to pose for a portrait in pastel, a portrait that became the first in a series.

After spending the morning posing and drawing, the two would stroll through the meadows behind her parents' house, discussing literature, art, and poetry, and wandering into the birch forest to be alone. Józefina later described those meetings as "something miraculous . . . inimitable experiences, which so rarely occur in life. It was the sheer essence of poetry."

Józefina grew up in Janow, the daughter of Zygmunt and Helena Schranzel, a Jewish couple who converted to Catholicism. In 1919, she officially changed her name from Schranzel to the more Polish-sounding Szelińska.

Bruno referred to her as Juno, a nod towards the Roman goddess of marriage and fertility. Every person has an animal resemblance, Bruno explained, and hers was with the antelope. As for himself, he resembled the dog.

"The artist absorbed the human being in him," Józefina said of Bruno, whom she likened to a kobold, or "a mythological sprite neither boy nor man, alternately virtuous, and mischievous." This mixture of innocence and dangerous jouissance characterizes her thinking of him.

Schulz came to visit her almost every evening of that summer in 1933; they discovered a shared adoration of Rilke, Kafka, and Thomas Mann. She was the first ear to hear many of the stories Schulz read aloud to her.

When she lost her teaching job in 1934, Józefina moved to Warsaw, and the two began a relationship of correspondence, which she described as “passionate letters that saved Bruno from his depressions”, attenuated by short visits in winter and summer holidays.

Maria Kasprowiczowa, the widow of a poet named Jan, invited the couple to her villa near Zakopane. The correspondence between Bruno and Maria was only discovered in 1992, when a scholar was rummaging through Jan Kasprowiczowa’s archives. But this correspondence offers insight into Schulz’s thinking about his beloved during this time.

On 25 January 1934, Bruno wrote to Maria:

The word "human being" in itself is a brilliant fiction, concealing with a beautiful and reassuring lie those abysses and worlds, those undischarged universes, that individuals are. There is no human being there are only sovereign ways of being, infinitely distant from each other, that don't fit into any uniform formula, that cannot be reduced to a common denominator. From one human being to another is a leap greater than from a worm to the highest vertebrate. Moving from one face to another we must rethink and rebuild entirely, we must change all dimensions and postulates. None of the categories that applied when we were talking about one person remain when we stand before another.... When I meet a new person, all of my previous experiences, anticipations, and tactics prepared in advance become useless. Between me and each new person the world begins anew.

In January 1935, Schulz’s brother, Izydor Sculz, died young of a heart attack, leaving behind a daughter, sign, and a mother who relied on him for financial support. A few months later, Bruno and Josefina made their engagement public.

Józefina "enslaves me and obligates me," Shulz wrote to Maria of his betrothed:

My fiancée represents my participation in life; only by her mediation am I a human being and not just a lemur or a gnome. ... With her love, she has redeemed me, already nearly lost and marooned in a remote no-man's-land, a barren underworld of fantasy….Is it not a great thing to mean everything for someone?

When he was granted a six-month paid leave in January 1936, Schulz elected to spend most of it in Warsaw with his fiancée. The two attended a dinner there, in that month, where Józefina raved about living in Paris after the wedding. But Bruno stared at his plate, saying nothing. When asked where he'd like to live after their marriage, Bruno answered: "In Drohobycz." A crack had opened.

Another complication was the rising anti-Semitism in the borderlands. The nomenclature of bureaucracy required Schulz to encounter identity as construed by the state. As mentioned, although Józefina was born to two Jewish parents, she converted to Catholicism (the official Polish religion) along with them, and also Polonized her surname—-a fact which may have saved her life once the Nazis took over.

Neverthless, that February, Schulz published an announcement in local papers that formally acknowledged his “withdrawal from the Jewish community” (in Balint’s words). Rather than register himself as Catholic, the official Schulz declared himself a man “without denomination.”

In spring 1936, Josefina translated the first edition of Kafka’s The Trial into Polish. Although Bruno’s name was also listed on the cover as a translator, the majority of the translation work belonged to her. Bruno’s afterword located Kafka in a sort of universal mysticism whose ideas “are the common heritage of the mysticism of all times, and nations.” For Bruno, Kafka lifts the “realistic surface of existence” and sets it atop “his transcendental world” in a sort of “radically ironic, treacherous, profoundly ill-intentioned” grafting.

One could say that Bruno and Josefina wrote a book together, a book whose author was also Jewish, also an Austro-Hungarian who imagined life in relation to his entrepreneurial father. One can also wonder how Bruno’s reading of Kafka influenced the trajectory of his own relationship with Jozefina.

When Józefina begged him to live with her in Warsaw, Bruno refused, referencing his sister’s illness and the needs of his family. Later, Józefina said that he was haunted by an image of himself "as a beggar, wandering the city, reaching out his hands, and I would turn away from him contemptuously." Bruno often mentioned this image when discussions about money and cohabitation began.

By January 1937, Józefina despaired of his commitment. His indecision made her "the weaker party in the relationship," she said. For where "he had his creative world, his high regions," Józefina felt that she "had nothing". She celebrated her 32nd birthday quietly. A few days later, she poured a handful of sleeping pills into her mouth and swallowed them. Wavering along the edge of unconsciousness, tasting the nearness of death, Józefina cried out for help and was taken to the hospital.

After learning of his fiancee's averted suicide, Bruno rushed to Warsaw to be with her. While at the hospital, Bruno caught influenza and spent 10 days in bed, completely enfeebled. With Bruno being treated for influenza, Józefina went to recuperate at her parents' home, near the birch forest where she and Bruno had spent countless memorable afternoons.

In February, Bruno appeared at her parent’s house, carrying figs, dates, and flowers. He surrounded Józefina with tenderness and devotion. "He felt guilt," she wrote later, adding that the guilt was "completely unfounded, for he was nothing but goodness."

But a plant can be beautiful and transient; a gift horse can begin a war; a romance can mean everything and go nowhere. And if Bruno was goodness to his betrothed, but he was also indecisive, unreliable, wracked with self-doubt and insecurity.

In the spring of 1937, Józefina ended their engagement and forced herself to stop answering his correspondence.

Neither Bruno nor Józefina ever married. After Schulz's murder by a Nazi, Józefina spent the next 49 years in fidelity to his memory. "To stay with him, for better or worse, forever," she wrote. That is the story she insisted upon.

As Esther Allen rightly observes, we have Joseph Roth’s books because of Michael Hofmann’s obsessive diligence as a translator. Or maybe, in his irredeemable complexity, Joseph Roth has us.

To be simultaneously vehement and committed to a neo-Romantic skepticism is not easy—-yet Roth managed it. His journalism and feuilletons on interwar Europe serve as glimpses into a past that could not predict the genocide in its future. Unlike other authors and scholars, Roth was difficult, which is to say, he refused to go along in order to get along with his peers.

Where, for example, Michel Leiris lionized the rituals of violence enacted by bullfights, Roth repeatedly editorialized against the inane cruelty of the sport. In a piece for Frankfurter Zeitung published on October 1, 1925, Roth describes the bullfight's role in placating the people of Nimes. (One can almost hear the Hermann Broch's Virgil groaning as he enters the emperor's festivities, and recognizes his pre-determined role in them.)

A young clownish fellow runs through the ring with a purple parasol, teasing the bull and performing for the audience, as Roth recounts:

Pursued by the bull, and shielded by the umbrella, he scrambles over the fence, and then, from his own cowardly safety, he jabs the umbrella into the bull's testicles. Huge laughter in the arena. The audience split their sides. The ugliest appurtenance invented by man becomes a weapon against the most appurtenance of the beast. The fellow couldn't have found a better expression of human dignity if he'd tried.

Once the bull is alone in the ring, Roth shifts into a supple act of identification with the tormented creature:

Bewildered, exhausted, foaming at the muzzle, the bull stops and faces the gate behind which, he knows, is the good, warm, protective shed, redolent of home. Oh, but the gate is shut and may never open again! The people are howling and laughing, and it seems that the bull has learned to distinguish between shouts intended to provoke him, and mere derision. A colossal contempt, bigger than the entire arena, fills the soul of the bull. Now he knows he is being laughed at. Now he no longer has the strength to be furious. Now he understands his helplessness. Now he has ceased to be an animal. Now he is the embodiment of all the martyrs of history. Now he looks like a mocked, beaten Jew from the East, now like a victim of the Spanish Inquisition, now like a gladiator torn to pieces, now like a tortured girl facing a medieval witch trial, and in his eyes there is a glimmer of that luminous pain that burned in the eye of Christ. The bull stands where he is and no longer hopes.

There is often this moment in which a vignette tilts towards embodied social critique in Roth’s nonfiction. He lures us in with details before holding a mirror to social behavior. But he doesn’t quite scold the reader. Nor does he moralize from a position of piety. He simply ambles along for another few paragraphs, providing a play-by-play of the bullfight, and then turns his pen to the spectators, the crowd watching the show, noting their impatience, their eagerness for action, the insatiable hunger that relies on its deniability:

The kindhearted, well-bred, polite citizens who take part in the game from a safe distance, by calling out fearlessly and brandishing heroic handkerchiefs, the tailors and hairdressers in their Sunday best—they are getting excited. Foam isn't enough for them anymore. They want to see blood, the good fellows!

Unable to fit into the crowd properly, Roth admits that he, like the “little white dog” belonging to a lady nearby, would prefer “to help” the bull. “But what can two poor pups like us do against five thousand people?” he asks, identifying himself with the dog rather than the humans present.

*

I’ve been thinking about Roth the critic . . . and the chimneys of Paris . . . and an essay Roth wrote about René Clair’s silent film, Sous les Toits de Paris (1930). . . and the way Clair, himself, described the origins of this film:

At the time I was shooting my second or third silent picture, I heard a circle of street singers in Paris, on my way home from the studios. I thought how sad it was that I had no sound with which to make a picture. Four years later, sound came, and I returned to my street-singers idea.

And about a comment Rene Clair made while shooting this film in May 1929—a concern about how the “monster” of sound might ruin cinema:

Can the talking picture be poetic? There is reason to fear that the precision of the verbal expression will drive poetry off the screen just as it drives off the atmosphere of the daydream. The imaginary words we used to put into the mouths of those silent beings in those dialogues of images will always be more beautiful than any actual sentences. The heroes of the screen spoke to the imagination with the complicity of silence. Tomorrow they will talk nonsense into our ears and we will be unable to shut it out.

The film’s original trailer is above—and the film is worth watching. In it, one can observe the techniques Clair developed to communicate those “imaginary words.”

For example, in the bar scene where the two male protagonists argue over Pola, the gramophone recording of Rossini's William Tell Overture starts to skip, creating an aura of sonic discord. Clair also shot the argument through a window, a technique that Sacha Guitry later borrowed to indicate unheard conversations.

But I wanted to talk about Joseph Roth’s commentary on this comedy, which he ends in a note of wistful uncanniness. “This sound film has all the charm of perdition,” he writes, continuing:

Not one of those playing here will ever leave this world. They will fall further and further into it, sink into the hill of years that come rolling up unstoppably, smiling, to the song of the accordion. Melancholy will always be a sister to their joys. They will always drink, love, throw dice, steal. Their fate is implacable. That's what gives the film its sadness. But the implacableness has a sheen of mildness, which makes it seem, as it were, placable. That's why it's such a joyful film.

The repetition. The absence of words to lay claim to a certain heaviness—- a logistical complexity of interpretation. The further and further of falling into family where melancholy dines with joy. The gorgeous irresolute resolution of a line like: But the implacableness has a sheen of mildness, which makes it seem, as it were, placable.

If you’d like to read Roth’s entire piece, you can download a PDF copy below (which includes annotations for no reason whatsoever, unless one counts my amusement and pleasure).

*

Joseph Roth, Report from a Parisian Paradise : Essays from France, 1925-1939, trans. Michael Hofmann and Katharina Ochse (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 2003): 202-205. Roth’s essay was originally published in Frankfurter Zeitung on October 28, 1930.

“Under the Roofs of Paris” (1930) as directed by Rene Clair is available from Criterion as well as Criterion Channel.

Riveting books curse this insomniac. Thus did I unintentionally burn my way through three midnights this week absorbed in Ross Benjamin’s translation of Franz Kafka’s diaries. I learned that Kafka’s 1908 included an unhappy love affair with a wine tavern waitress named Julianne Szokoll (Hansi). Max Brod said that there was a photo of her standing next to Kafka, and that Kafka said of Hansi "that whole cavalry regiments had ridden over her body."

There are themes— which I will paginate, due to time constraints.

Reproaches

The reproach is thematic to the diaries as well as Kafka’s fiction. On May 18th or 9th of 1910, as Halley’s comet whirs past, Kafka develops his inflamed inventory of reproaches against parents and family. He reproaches his mother and father for his education, and what they failed to teach him; page 7. Both reproach and refutation do him great harm, Kafka tells us on page 8. Addresses the “group pictures “in a fabulous way. Talks about how he introduces them to each other, these family members, these people who have harmed him.

Strangers allow him to detach his mind from the reproaches. Looking out the window quiets “the urge to reproach.” He looks out the window often when standing in a room with his father. Or he begins a scene near a window. Or he uses the movement towards as a window as a transitional device between interior monologues. Or he returns to an image of his father looking out the window. (“Men looking through windows” could be a song on Kafka’s greatest hits.)

After reproaching his family for their failure, Kafka reproaches them for their love, for those who have done him “harm out of love, makes their guilt even greater." For Kafka, family love is almost more dangerous than hate, or more damaging.

Also: "Parents who expect gratitude from their children (there are even those who demand it) are like usurers, they are happy to risk the capital as long as they get the interest."

Epistles

"I have no time to write letters twice," Kafka confessed on November 27, 1912. No time to preserve a copy of his own words—no time for correspondence. Since Kafka’s relationship to the epistolary genre is part of my work-in-progress, take this quote as a large star or a comet. Letters are not different from literature to Kafka—-in fact, many of his letters (particularly those related to Felice Bauer) wind into his fictional characters.

The letter at the top of this post, which Kafka addressed to Felice Bauer’s parents—-after reading Kierkegaard—-breaking off their engagement; the timing is uncanny. The theory of letter malaise excerpted below ties is also critical. Kafka hated being presented with choices, or making large decisions; each decision was approached as a momentous life-changing event.

Restlessness and indecision = anxiety

(13 Sept. 1915): "I don't have to make myself restless. I'm restless enough, but for what purpose…how can a heart, a not entirely healthy heart bear so much dissatisfaction and so much uninterruptedly tugging desire."

Again and again, Kafka defines anxiety as the dread of making a choice, since the interpretations of others will determine the meaning of that choice. The trial is ongoing, and there is no end to it. Dread is simply the awareness of an impending choice, or the space after a decision has been made in which the choice will be interpreted by others. Society writes the book of one’s self daily. Refusing their misinterpretation is why one writes the novel.

Conscientia scrupulosa (scrupulous conscientiousness)— the expression Max Brod used to describe Kafka’s obsessive relationship to moral dimensions, and his inability to “overlook the slightest shadow of injustice that occurred.” In Brod’s view, Kafka is driven by this belief in “a world of Rightness.”

Diary as self in time

Diary as encounter with self in relation to time:

"In the diary one finds proof that, even in conditions that today seem unbearable, one lived, looked around and wrote down observations, that this right hand thus moved as it does today, when the possibility of surveying our condition at that time does make us wiser, but we therefore must recognize all the more the undauntedness of our striving at that time, which in sheer ignorance nonetheless sustained itself."

*

As for Benjamin’s translation, it is the dream of every end-note aficionado to discover the details and traces. Take end-note #577, for example: “The poet, playwright, and composer Abraham Goldfaden founded the first Yiddish theater troupe in Romania in 1876; he is regarded as the founder of the Yiddish theater.” BYOB to the Kafka revival.

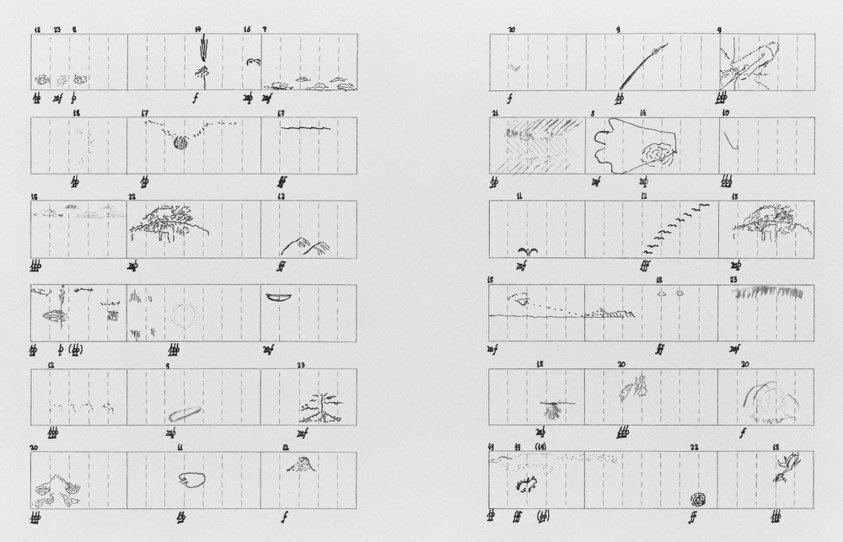

“Score without Parts (40 Drawings by Thoreau): Twelve Haiku, 1978” by composer John Cage is currently housed in the Princeton Library, which describes the piece as follows:

In this work, Cage, who is among the most influential composers and conceptual artists of the postwar avant-garde, duplicates the score with which he conducted his 1974 composition Score (40 Drawings by Thoreau) and 23 Parts. Inspired by the writings of the American naturalist Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862), the artist replaced conventional musical notation with small drawings of natural elements—seeds, animal tracks, and nests—drawn from Thoreau’s journal, which Cage selected and sequenced at random with the aid of the I Ching, an ancient Chinese divination text. He then divided each of the twelve bars into three sections of five, seven, and five measures, transforming the score into a visual, sonorous, and experiential haiku.

Brian Eno’s “Three Variations on the Canon in D Major” (on the B side of his album Discreet Music) took a canonical piece, Johann Pachelbel’s Canon in D, and “varied” it. Although some musicologists claim Discreet Music the origin of ambient music, the first ‘official’ ambient was Eno’s Ambient 1: Music for Airports, which came three years later.

“Ambient Music must be able to accommodate many levels of listening attention without enforcing one in particular; it must be as ignorable as it is interesting,” Eno explained. And there is movement from the word discreet, which connotes a quietude and reticence, to the word ambient, which suggests the creation of a certain environment.

The challenge Eno set for ambient music—-being simultaneously ignorable and interesting—reminds me of Proust, laying in bed, writing an entire world from his convalescence. Or maybe it reminds me of convalescence in general, and the way in which confinement, or restriction, or the constraint of the bed shapes the way objects are received and experienced.

In Eno’s telling, he was bedridden and unable to move when the inspiration for Discreet Music occurred. Recovering from a car wreck in 1970, a friend came over to visit him. As she was leaving, she asked him if she should put a record on, since he couldn’t rise to do this himself. This question about whether he wanted music feels tied to the question of what sort of environment he preferred to stew in. After putting on a record, the friend left. But the volume of the music was too low, the melody was “much too quiet,” and Eno couldn’t reach the record player to turn up the volume. “It was raining outside,” Eno recalls. “It was a record of 18th-century harp music, I remember”:

I lay there at first kind of frustrated by this situation, but then I started listening to the rain and listening to these odd notes of the harp that were just loud enough to be heard above the rain.

Discreet Music‘s B side performs a reinterpretation of its own with variations on Johann Pachelbel’s Canon in D, “Fullness of Wind,” “French Catalogues,” and “Brutal Ardour.” On Eno’s instructions, the Cockpit Ensemble repeated parts of the score while gradually altering it, imbuing this familiar (not least from weddings) 17th-century piece with an otherworldly grandeur. Like their mistranslated-from-the French titles, these variations may in some sense be “mangled,” but they become all the more ambiguously evocative for it.

The liner notes from Eno’s Music for Airports.

And, of course, the opportunity to drop one of my favorite albums of Eno’s, namely, his collaboration with King Crimson’s Robert Fripp on “Evening Star.”

Fripp Eno - Evening Star from León Pedrouzo on Vimeo.

An elegy is a poem which mourns the end of a life, and lays out the particulars and characteristics of a particular loss.

The traditional elegy resembles the plaza monument in how it sets out a community's grief at the loss of a figure held in common. Elegies invoke the funerary customs and ritual of the society in which this death happens, or in the community's expression of loss. In some ways, the power of the elegy resembles the power of collective memory and community.

I think the elegy, more than any other form, creates the possessive plural pronoun — the Our— in relation to its subject. This is our hero who died; we are now defined as part of his lineage; our lives are interpreted in relation to his actions.

As Eavan Boland and Mark Strand have written, "the best elegies will always be sites of struggle between custom and decorum on one hand, and private feeling on the other." One sees this in W. H. Auden's elegy, "In Memory of W. B. Yeats," where the speaker alternates between intimacy and conventional decorum. You can almost track this shift from section to section.

Section 1, for example, creates a sense of place carved out by loss:

But for him it was his last afternoon as himself,

An afternoon of nurses and rumours;

The provinces of his body revolted,

The squares of his mind were empty,

Silence invaded the suburbs,

The current of his feeling failed; he became his admirers.

Auden highlights this last moment of being, the final instance of inhabiting the known selfhood, and the shift which occurs is memorial, which is to say, now his admirers will define him.

I thought of the poetics of dementia, and the particular loss enacted by Alzheimers; the one who loves the Alzheimer's patient seems to hover at the doorway of this last moment— the last moment in which they are themselves in the slow erosion of selfhood.

The words of a dead man

Are modified in the guts of the living.

Auden loops back to Yeats, or to the body on bed who became his admirers. And Auden is one of these admirers who carries Yeats into the future.

Section II changes pace, and performs a sort of reversal. Unlike the other sections, this one exists in a single stanza:

You were silly like us; your gift survived it all:

The parish of rich women, physical decay,

Yourself. Mad Ireland hurt you into poetry.

Now Ireland has her madness and her weather still,

For poetry makes nothing happen: it survives

In the valley of its making where executives

Would never want to tamper, flows on south

From ranches of isolation and the busy griefs,

Raw towns that we believe and die in; it survives,

A way of happening, a mouth.

Section III tightens the form, hewing to meticulous rhyme schemes, gesturing towards a song-like structure which resembles decorum, or conventions for mourning a public figure. Even the beginning seems to clear its throat; the first quatrain arranges itself behind the podium:

Earth, receive an honoured guest:

William Yeats is laid to rest.

Let the Irish vessel lie

Emptied of its poetry.

The mournful statement has been made, and this final section resembles a traditional funeral eulogy. What fascinates me in this final section is how Auden puts on his Sunday best (in the first section, he's wearing jeans and golf shirt); he smooths his tie and straightens his cuff-lengths in six tidy, isometric quatrains.

This tidy sombreness is the marble from which monuments are made.

Here are the final two quatrains in Auden's poem:

With the farming of a verse

Make a vineyard of the curse,

Sing of human unsuccess

In a rapture of distress;

In the deserts of the heart

Let the healing fountain start,

In the prison of his days

Teach the free man how to praise.

End-rhymes also add to the monumental texture of Auden’s poem. One of the decisions a poet makes involves the poem’s relation to statues, to shadows, to the monumental tradition invoked by form. And each poem asks something different of the poet. At our best, we are attuned to this. At our worst, we are human.

- Ulalume González de León, “Syntax” (translated by Terry Ehret, John Johnson, & Nancy J. Morales)

Syntax—or the way the basic components of a sentence are arranged, connected according to phrases and clauses, and extended to other sentences—comes from the Greek syn (together) and tax (to arrange), meaning the orderly or systematic arrangements of parts or elements.

“Each is embedded in the syntax of the moment—” said Marvin Bell.

*

“The poem is itself essentially a body, comprised of various parts that work in various relation to one another–which could also be said, I know, of machines, but because poems are written by human beings, these relationships are unpredictable. A successful poem will never feel robotic or mechanized. It feels felt.”

- Carl Phillips, “Muscularity and Eros: On Syntax”

*

“The line is no arbitrary unit, no ruler, but a dynamic force that works in conjunction with other elements of the poem: the syntax of the sentences, the rhythm of stressed and unstressed syllables, and the resonance of similar sounds.”

- James Longenbach, The Art of the Poetic Line

Longenbach’s three kinds of poetic lines include parsed lines, annotated lines, and end-stopped lines. O, kudos to Frontier Poetry for this resource!

*

“It is this question of grammatical phrasing and ending that orchestrates relationships between syntax and the poetic line.”

- Shira Weiss, “Syntax and the Poetic Line”

*

Lines can contain what is called a memory of meter rather than meter.

*

“Why not consider parallelism a type of prestidigitation, where subtle shifts in prosodic execution stack in such a way that we do not get the chance to see how quickly and sometimes violently the poem has changed? A word has been “put out of place,” a speaker who once held on to an orderly image of flying birds has become the very perch upon which the birds may sit. Meanwhile, the structure of the poem turns and entangles in its own (il)logic, and the likelihood of closure falls into deferment. But does not deferment of closure, of pleasure, carry the potential of intensifying pleasure once it finally arrives, a kind of driving one out of their mind?”

- Phillip B. Williams, “Wandering Through Wonder: Parallelism and Syntax in the Poetry of Carl Phillips”

More closely, Williams lists the following ways a poem can turn at the volta:

A reversal of what was just said comes into play.

A shift in mode: narrative to lyrical, lyrical to dramatic, dramatic to narrative, etc.

A shift in the spatiotemporal, meaning the when and where of the poem changes.

A shift in voice, meaning the actual embodiment of the speaker changes.

A shift in tone, often times signaled by a rhetorical shift. Meditative to enraged. Curious and deciphering into sure-hearted and self-engaged. Thinking about rhetoric, does the speaker move from listing to directive? Statement to question?

Each of these formal decisions—-each of these turns—-relies on choices about syntax. Each is an opportunity to make it “feel felt,” as Phillips has said.

*

“I mean, syntax is always about ascribing hierarchy, right? Syntax is a matter of who/what comes first, of what entity or force acts or is acted upon, and so on. When I play inside the constraints of this order, I’m playing so as to expose machinations that hum beneath familiar cadences, the under-rhythms and the ideas they carry. I want the arrangement to come under scrutiny. I love when syntaxes fold, repeat, contradict, and undo themselves to reveal their and our hypocrisies. I love the experience, while writing, of stumbling onto coded meanings in habitual language patterns and then defamiliarizing or destabilizing them. And I’m most interested in: What becomes possible after that?”

- Ari Banias in “The Politics of Syntax and Poetry Beyond the Border” by Claire Schwartz

*

“Syntax provides the opportunity for lines that are usually end-stopped, usually by means of a punctuation mark, and for lines that are enjambed because the sentence runs to the next line. Most free verse writers like to mix end-stopped and enjambed lines so as to create an individual sound, and to provide surprise and reward in the text. Syntax provides the opportunity for changes in pitch, pace, and tambour. Syntax and rhythm define a tone of voice far more than do vocabulary and lining. Line holds hands with syntax, and syntax holds hands with rhythm. The more kinds of sentences one can write, the more various can be one's poetry, whether metered or free. Syntax creates grammar and logic too, though in the end, music always wins.”

- Marvin Bell, after calling syntax “the secret to free verse” in a workshop

*

In an essay on Trevor Winkfield, John Ashbery described "sight-reading" a painting, or noticing how each element in the painting has "its precise pitch, its duration." One thinks of the hard, jewel-like poems that want to dissuade us from drawing closer. The quick clip of monosyllabic syntax and fricatives.

*

Language relates – and the words we use tell the reader what sort of relationship is brewing.

Haryette Mullen compared Stein’s syntax in Tender Buttons to “baby talk”, which she defines as "a magical marginal language used mainly by women and children.” For Mullen, the minor and the marginal are potential sites of freedom, and so she chooses the prose poem, which she also describes as a "minor genre," as the form to carry the words about gendered clothing in trimmings.

*

“Because many poets like a poem to look like a column, much free verse has the feel of accentual verse, in which one is counting the number of stresses in each line. These poems often are a conversational three-, four-, or five-beat line, with an occasional line a beat shorter or longer. Free verse at its most free verse-like is elastic: Some lines are noticeably shorter or longer than others, and each is embedded in the syntax of the moment. As a young poet, I sometimes follow the early example of William Carlos Williams and the later example of Robert Creeley, for example, enjambing short lines in jazzy syncopation. Thus, it seemed important to hesitate slightly at the end of each line.”

- Marvin Bell, again

*

Metaphor positions us in a counterfactual relation to the world of ordinary speech and conversation. It puts us in what Anne Carson calls "an uncanny protasis of things invisible" which doesn't seek to argue with (or even refute) the known world so much as "to indicate its lacunae".

A counterfactual sentence can operate as a vanishing point for these two perspectives that lay in symmetry, or in protasis, in the conditional relationship. Syntax is how this vanishing is set up. Syntax determines its reach, texture, and duration.

*

"And we have to figure out what these coins mean, not

knowing the language."

- John Ashbery, "Flow Chart Part II"

I found a reference to Frank O’Hara’s “Ode to Necrophilia” in C. D. Wright’s essay “the new american ode.” Having never read this particular O’Hara ode, discovering an urge to do so, feeling needled by a vague curiosity, I searched for it—and settled for transcribing this visual screen-print created by by Michael Goldberg and Frank O’Hara in 1961.

Michael Goldberg & Frank O’Hara, "Ode to Necrophilia", screen-printed 1961. From the book Odes.

ODE ON NECROPHILIA

by Frank O’Hara

“Isn’t there any body you want back from

the grave? We were less generous in our

time.” Palinarus (not Cyril Connolly)

Well,

it is better

that

OMEON

S love them E

and we

so seldom look on love

that it seems heinous

This should be the end of the story, according to plot scheme mapped as 1) reader wants to eat a poem described a writer 2) reader finds poem 3) reader satisfies hunger with poem 4) reader makes notes on the feast itself. But the feast turned into a correspondence.

O’Hara’s ode fed me directly to Kati Horna’s gelatin silver print series, Oda a la Necrofilia (Ode to Necrophilia) from 1962. One year after O’Hara and Goldberg’s publication, Horna (who lived in Mexico City) created this photo-narrative of a woman grieving a death. Perhaps necrophilia was in the chemtrails of the early 1960’s.

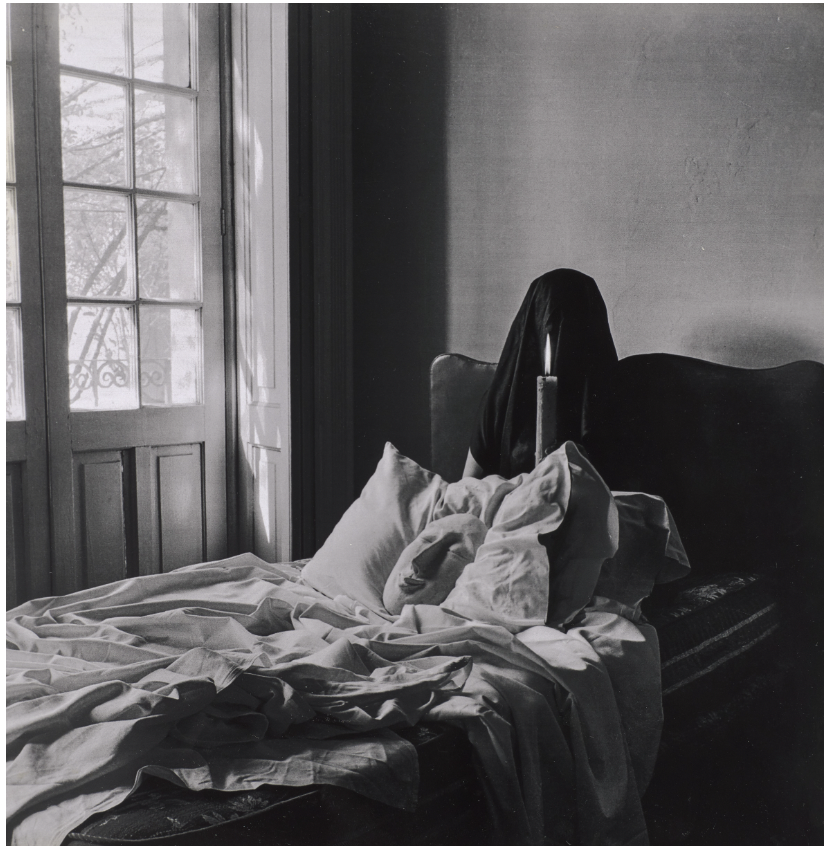

The Oda a la Necrofilia series was originally published in Salvador Elizondo’s avant-garde journal, S.nob, for which Horna coordinated the section on “Fetishes.” The only title I’ve found for the piece below is “Untitled.” It is incredible.

We know someone has died because the large plaster death mask lays on the pillow. At the head of the bed, hidden beneath the black fabric, a silhouette of a figure. The fabric is a mantilla, the traditional lace shawl worn by Spanish and Mexican women during mourning and on holy days.

Commemorative: the lit candle in the foreground. A half-open porch door with sunlight spilling onto the wall. The tension between the candle’s small flame and the bright light filling the room.

The figure beneath the mantilla is Horna’s friend and artistic collaborator, Leonora Carrington.

Leonora (Ode to Nechrophilia series), signed 'Kati Horna' (on the verso, gelatin silver print, sheet 8 1/8 x 7 1/2 in. (20.6 x 19.1 cm), executed in Mexico City, circa 1962.

Horna’s photo-narrative is silent, enigmatic, hued towards the erotic, and centered on Carrington’s interaction with various objects.

The shifting spatial relationship between the mourning body and the objects resembles a grieving process in which various defenses or forms or protective covering are shed. Once the mantilla is removed, the woman stands in her bra, smoking a cigarette, cradling the mask as if the absent could share the smoke with her.

The empty ankle-boots look so awkward poised ballerina-style near the bed. Are they hers or his?

Carrington watches herself smoke in the mirror to the left, and we see her reflection lit by the sunlight. The black umbrella is part of grief’s traditional costume in some villages, but I’m not sure if this is true in Mexico City, where Carrington posed for this photo series with Horna.

Clearly the black umbrella serves no useful function inside the room. If anything, it is—-like the cigarette and the cradling of the death mask—-a courting of bad luck. Opening an umbrella indoors is bad luck in most cultures. Is there a defiance in photo titled “Leonora”? Is there a risk?

There is—-I believe—a cigarette tucked behind Carrington’s ear.

The light moves to the white of the mask in her lap. The sheets are pulled back as if she is preparing to climb in bed with the mask.

The umbrella is open, hiding her face. A stroke of reflected light, like something shot from a mirror, on her left shoulder.

I don’t know the correct sequence of this series, so there is a sense in which I am inventing the story as I go, which means missing the story Horna intended.

Leonora (Ode to Nechrophilia series), signed 'Kati Horna' (on the verso, gelatin silver print, sheet 8 1/8 x 7 1/2 in. (20.6 x 19.1 cm), 1962. “Standing as fetish for the body of the deceased, a white mask carefully placed on top of a pillow becomes the recipient of the woman’s sorrow and desire.”

I don’t understand how Horna created this doubled-headboard effect. The shadow of the headboard interacts with the naked back and the absence of Carrington’s face in an extraordinary way— a melange of erotism and agony.

And the porcelain jug holding the candle: the subtle tension between this bedside, water-bearing vessel which is holding a lit object that lights the plaster face on the pillow. Grief is the story where form detaches from function.

The three images above are housed in L. A.’s Hammer Museum.

An inventory of moving objects in this series: the white mask, the candle, the pillow, the black mantilla, the unmade bed, the umbrella, the cigarette, the ankle-boots, the open book, the jug, the woman’s body in various states of undress.

A note on the artist: Kati Horna was born in Budapest, Hungary to an upper middle-class Jewish family. She learned her craft from the renowned photographer, József Pécsi.

In the late 1920’s and 1930’s, Horna moved across Europe from Berlin to Paris to Barcelona to Valencia taking photos for the illustrated press. Demand kept her moving through war zones in the interwar period, but it was Spain that affected Horna deeply, particularly after she got involved with the anarchist fringe in the Spanish civil war and began creating photos and montages for their propaganda materials. These anti-fascist agitprop materials combined satire with intense hope, two tones one can feel in Horna’s later work, where loss encounters itself as a continuous displacement, a reenactment among objects, a gestural dance with disillusionments.

In late 1939, as Nazism moved into the mainstream, Horna left the continent and settled down in Mexico City where other radicals and surrealists congregated. This is where she met Carrington, who had moved to Mexico knowing no one and speaking zero Spanish. Painter Remedios Varo had also come from Spain to Mexico, and Carrington and Horna may have rubbed elbows with other surrealist women, including Anna Seghers. (The international anthology, Surrealist Women, might have details, or else entirely disprove my wild speculations.)

Artist Pedro Friedeberg named Horna and Carrington as inspirations on his work and this should be the end of the end of the story about odes to necrophilia, if not for my failure to define the oded noun, itself.

Necrophila americana male (left) and female (right).

*

Necrophilia—-not to be confused with Necrophila, a genus of beetles—also known as necrophilism, necrolagnia, necrocoitus, necrochlesis, and thanatophilia, is sexual attraction or act involving corpses. It is classified as a paraphilia by the World Health Organization (WHO) in its International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnostic manual, as well as by the American Psychiatric Association in its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM).

Adjacently, as reportedly inspired by O’Hara’s poem, in a stack of necrophilia and Twilight-hustling Goodreads posts—

It should also be noted that Marjorie Perloff, author of Frank O'Hara: Poet Among Painters, explained how Goldberg and O’Hara got involved:

O'Hara turned to art because the literary scene was so dead at the time. He disliked Robert Lowell, who was the prominent poet then but had no interest in the art of his day—especially not Jackson Pollock. Nor did [Lowell’s] contemporaries. O'Hara opened that up. When I wrote my book in 1976, saying that he was a notable poet of the period, people said it was ridiculous. Now there is enormous interest. The variety, good humor and charm in his work are tremendous.

Necrophila americana is a sonnet series waiting to be written by a suburban beetle in the auspices of a romance with a reading list.

A LINE-SCRAMBLE

A list which retains the exact line and punctuation of the poems in no particular order, updated lazily.

*

At a hotel in another star. The rooms were cold and

[Jean Valentine, "If a Person Visits Someone in a Dream, in Some Cultures the Dreamer Thanks Them"]

the millisecond I was born to look up into.

[Jorie Graham, “History”]

the way a mountain is land and a harbor is land and a parking lot

[Ari Banias, “Oracle”]

the uncontrollable mystery on the bestial floor.

[W. B. Yeats, “The Magi”]

It will not be a part of the weather.

[Charles Wright, “The New Poem”]

How even a little violence

[Joan Baranow, "The Human Abstract"]

it does not mean we are about to die

[Zachary Schomburg, "Love is When a Boat is Built From All the Eyelashes in the Ocean"]

Nothing approaches a field like me. Hard

[Donika Kelly, “Love Poem: Centaur”]

Poem that at each door believes itself

[Sophie Cabot Black, “Love Poem”]

this is the edge between what is and what is not.

[Patricia Fargnoli, “Then”]

I am trying to invent a new way of moving under my

[C. D. Wright, “Crescent”]

the fatigued look of relief on post-coital faces,

[Dean Young, “The Euphoria of Peoria”]

With my eyes closed I saw:

[Rachel Zucker, “After Baby, After Baby”]

nightly toward its brightness and we are on it

[C. D. Wright, “Crescent”]

Time will append us like suit coats left out overnight

[Charles Wright, “Still Life with Spring and Time to Burn”]

In a thousand furnished rooms.

[T. S. Eliot, “Preludes”]

The bed and desk both want me.

[Rachel Zucker, “After Baby, After Baby”]

Instinct will end us.

[Charles Wright, “Easter 1989”]

It's sacrilege to imagine

[Sarah Vap, “Reconcile”]

That landing strip with no runway lights

[Kim Addonizio, “My Heart”]

because there are seven kinds of loneliness

[Marty McConnell, “the fidelity of disagreement”]

Find me home in New York with the Alone

[Allen Ginsberg, “Personals Ad”]

It is the sea that whitens the roof

[Wallace Stevens, “The Idea of Order at Key West”]

Dear Reader, I thought

[Dean Young, “Dear Reader”]

I don’t see anything at the end of it except an endlessness . . .

[Larry Levis, “Boy in Video Arcade”]

Evening comes soft and grey like

[Wong May, "In Memoriam"]

If I fall

[Zachary Schomburg, "Love is When a Boat is Built From All the Eyelashes in the Ocean"]

and green how I want you green, that house of am

[Karen Volkman, “Sonnet”]

We were never the color-blind grasses,

[Larry Levis, “Elegy with an Angel at Its Gate”]

Think of death, then, as an open season.

[Jesse Lee Kercheval, "I Open Your Death Like a Book"]

All we are is representation, what we are & are not,

[Larry Levis, “Elegy for Whatever Had a Pattern In It”]

The body knows, at most, an octave

[Deborah Digges, “To Science”]

Hi, I’m Asphodel, the flower of hell,

[Angela Vogel, “Asphodel”]

Sometimes he demands a sacrifice.

[A. E. Stallings, “Palinarus”]

Sitting along the bed’s edge, where

[T. S. Eliot, “Preludes”]

No one chose me

[Claudia Keelan, “Little Elegy (1977-1991)"]

A man walked into the drugstore and said "I'd

[Frank O’Hara, “The eyelid has its storms…”]

One day, the fox doesn't show.

[Dean Young, “The Fox”]

The way the world is not

[Bill Knott, "Sonnet”]

I'm through with you bourgeois boys

[Bernadette Mayer, “Sonnet”]

The windows, the view, the idea of Paris.

[Rachel Zucker, “After Baby, After Baby”]

The grimy scraps

[T. S. Eliot, “Preludes”]

beneath the mattress

[Zachary Schomburg, "Love is When a Boat is Built From All the Eyelashes in the Ocean"]

I swear before the dawn comes round again

[W. B. Yeats, “The Fascination of What's Difficult'“]

Every sky

[Matthew Henriksen, "Afterlife with a Gentle Afterward"]

Collate foliage into freezer

[Dannyka Taylor, "Improveras, I Heart Abandonment"]

The inside of a car

[Claudia Keelan, “Little Elegy (1977-1991)"]

to romanticize. Think of the train cars

[Paul Guest, “Poem for the National Hobo Association Poetry Contest"]

My nightmares are your confetti

[Dean Young, “Dear Reader”]

And therefore I chose, leaving behind what was supposed to be left behind—

[Patricia Fargnoli, “Then”]

The notion of some infinitely gentle

[T. S. Eliot, “Preludes”]

is a greedy thing. We thought we understood

[Jayne Pupeck, "Scheherazade"]

got high on the sublime lightness of desolation,

[Brian Smith, “What Will My Urn Say, Maybe”]

See the photon trespassing the wide pupil. See the soul

[Jaswinder Bolina, "You'll See a Sailboat"]

writing a letter

[Jean Valentine, "If a Person Visits Someone in a Dream, in Some Cultures the Dreamer Thanks Them"]

Every face exists for at least one illusion

[Matthew Henriksen, "Afterlife with a Gentle Afterward"]

What made anyone think I was a Communist I don’t know. I never went

[James Tate, “The Argonaut”]

committee for this shitty city.

[Angela Vogel, “Asphodel”]

sad blue satchel,

[Jesse Lee Kercheval, "I Open Your Death Like a Book"]

it was all perfectly normal. In ruins

[Chad Bennett, "Gerhard Richter"]

Past the cannibals of diction, rhetoric in its coffin

[Terrance Hayes, “The Blue Sylvia”]

I went to the zoo and talked to the animals. I dreamed I had an affair

[James Tate, “The Argonaut”]

we die amid the fumes of our uncertain words.

[Paul J. Willis, “Letter to Beowulf”]

You, my adoration—no fooling—I've

[Hayden Carruth, “Adoration is Not Irrelevant”]

your bones already asterisks,

[Dean Young, “Dear Reader”]

I am sleeping with another woman.

[Ian Harris, “Factbook”]

Blue is the tarp, blue the crane,

[Randall Man, “South City”]

characters in works of fiction.

[Rodney Jones, “Fears”]

You have soft hands. Because when we moved, the contents

[Matthew Olzmann, "Mountain Dew Commercial Disguised as a Love Poem"]

I remember that I am falling

[W. S. Merwin, “When You Go Away”]

Bumped into some Lucy Sante excerpts on masks today. And was reminded of how well some writers describe the tension of images. For example:

The wig isn’t a cheap one, and its slippage might be deliberate. It serves in combination with the mask to give her a passingly eighteenth-century aspect: a debauchee airlifted from a painting by Fragonard and deposited, a bit the worse for wear, in the pages of Juliette. The photograph is a circular riddle that causes the viewer’s eye to travel, back and forth, from south to north pole and back again, always somehow expecting a resolution that is locked away forever.

Here is what Sante says of “the panto-mask” pictured above:

“The mask that is no a concealment but an enhancement”— what a supple metaphor for writing in form, or slipping into a formal constraint invented by others. The mask reveals according to the mask’s conventions. And those conventions are limitations, or boundaries, on how exposition takes place.

I’m fascinated by the way photographs and texts aim towards a similar preservation-through-presentation of selves and selfhood. Reading a lot of Bhanu Kapil lately, immersing myself in her Cixousian borders and syntax, and (of course) browsing Kapil’s reading lists and invocations of possible literary lineage. In an interview with Laynie Browne, Kapil listed the following novels written by poets which inspired her: “Gail Scott's My Paris and The Obituary; Sina Queryas’ Autobiography of Childhood; Melissa Buzzeo’s What Began Us and The Devastation; Laynie Browne’s The Ivory Hour (a future memoir); Laura Mullen’s Murmur.; Juliana Spahr and David Buuck's Army of Lovers collaboration; Chris Abani’s Becoming Abigail; Renee Gladman’s Juice; Laura Moriarty’s Ultravioleta; Douglas Martin’s Your Body Figured and Elena Georgiou’s unpublished novel on the Crimean war.”

The mask reveals according to the mask’s conventions. The moth dangles vertically as it develops. I learned this from watching things my children have nurtured and monitored through glass windows, in a way that approximates our own most “civilized” notions of parenting and education.

It is easy to pretend the glass isn’t there, or that something objective is occurring—something that doesn’t partake of subjectivity. This ease should should make us suspicious, for nothing true is characterized by ease, and no gaze lacks the bias of its origins and socialization.

Back to Kapil—to language and questions and masks and vertical approaches. Her prose poetry collection, The Vertical Interrogation of Strangers is arranged using a series of twelve repeated questions, and integrates the answers of various women alongside her own.

Ranging across maps and locations, including Punjab, Central America, England, Arizona, and the US, the speaker meditates on the "interrogations" in fragmented form, in apostrophe, in aside, in dramatic monologue, in repetition of sensual images (candles, baths, skin, etc) without settling, or providing a settled image of the speaker. I read this nomadic texture of female selfhood as a soft dismissal of modernity’s sessile, fully-realized selfhood. But one can read Kapil many ways, I think; her work aims towards that multiplicity and fracture.

Kapil’s 12 Questions for the Vertical Interrogation of Strangers

1. Who are you and whom do you love?

2. Where did you come from / how did you arrive?

3. How will you begin?

4. How will you live now?

5. What is the shape of your body?

6. Who was responsible for the suffering of your mother?

7. What do you remember about the earth?

8. What are the consequences of silence?

9. Tell me what you know about dismemberment.

10. Describe a morning you woke without fear.

11. How will you / have you prepare(d) for your death?

12. And what would you say if you could?

There is a poem in this… or a writing exercise, a way of restricting one’s self to fragments as responses, and answering each of Kapil’s questions in a line, in something like a vertical interrogation poem. To illustrate by riffing:

A porch with no ontology loves the lie of sunshine.

Maybe a sperm met an egg and then fled on an airplane.

Convene in a language where no one knows his name means “longing.”

Milliseconds don’t exist in an hourglass figure.

When they opened the hotel room door, she was dead on the bed.

Already en route to dust.

Quiet decomposes. Sonatas die if no one hears them.

Maybe the unsung never existed.

….. (and so on and so on…. just filling in elliptical answers to difficult questions, and riffing into the emergent terrain of ideas)

A vertical interrogation sonnet would answer each of these 12 questions in fragments or statements, and then work those 12 lines into 14 lines by experimenting with lineation, enjambment, and substitution.

Iamb if you want. I am seeing sonnet prompts everywhere now it seems.

Inside of front cover of Paul Nash’s Aerial Flowers. Includes inscription to Eileen Agar from Margaret Nash. From Tate Museum Collections.

Conceit connotes snobbishness, a certain smugness or certitude, more unbearable to the extent that it is unwarranted. I love leaning into Walker Percy’s metaphor of the writer as an alien anthropologist visiting Planet Earth, shaking his alien head in wonder. (I’m so full of wonder that I can’t permit an alien species without it, not even in my most vehement imaginings). Nothing is more conceited than man, an upright mammal who posits himself at the center of a universal drama by creating a god in his image, to reflect his greatness. It’s wickedly good. Of course the reader wonders how it will play out.

As for the literary conceit, what could more obvious, more prevalent, more implicated than ecology? On a planet where man, the dominant species, invents a deity that creates for the purpose of conflagration. When I sit down to write the honeysuckle, I have to actively avoid slipping on the green goggles. Isn’t climate change and ecological destruction the crib of things? Isn’t seeing green the skinned knuckle of a poet’s hand whenever they reach to feel a rock? Read Brenda Hillman’s “Poem for a National Seashore”. Dander through eco-poetics. Submit to anthologies that engage the most elemental and incredible conceit. And please send links if you’ve published a poem on this spectrum of life. I want to read it. I want to see what we’re destroying to sustain our unsustainable lifestyles.

Aerial Flowers, by Paul Nash. Page 8. Includes black and white reproduction of 'Cumulus Head'. (From the Tate Museum website.)

The sublime is part of this conceit. And sublimity is quite creepy— it is the bane of materialisms, the inexplicable and unreliable ecstasy. Precisely because statistics, data, and numbers are easily manipulated, I am quite interested in unreliable ontologies. In an essay, “On Sublimity,” Martin Corless-Smith quotes from page 5 of Paul Nash’s Aerial Flowers:

A few years later in the course of making a series of drawings to illustrate Sir Thomas Browne’s Urne Buriall, I came upon the sentence referring to the soul visiting the Mansions of the Dead. This idea stirred my imagination deeply. I could see the emblem of the soul—a little winged creature, perhaps not unlike the ghost moth—perched upon the airy habitations of the skies which in their turn sailed and swung from cloud to cloud and then into space once more. It did not occur to me for a moment that the Mansions of the Dead could be situated anywhere but in the sky…the importance of this particular opportunity was that it afforded a further adventure in flight.

The ghost moth. The Mansions of the Dead. Eco-poetics and ghost moths—a soil aerated by sublime possibility for the writer.

1. 1

“The future, the word, and the unknown are . . . linked. Words which consciously aspire to the future are heightened by the desire to rise, be free of, the tyranny of history.”

- Fanny Howe

“Oh! kangaroos, sequins, chocolate sodas!”

- Frank O'Hara

“Bodies have their own light which they consume to live: they burn, they are not lit from the outside.”

- Egon Schiele

Egon Schiele, in one of his many self-portraits. The frame of the sonnet is so tight somehow, so pre-drafted, that it makes a lovely vehicle for the self-portait. Or for a series of self-portraits.

I A. Richards defined poetic tone as the speaker's attitude to the listener. The tone of Schiele’s self-portraits is uniquely brutal. Ornately brutal—brutalesque. Like Tomaz Salamun’s “Status Sonnet”… The way the poem or painting uses its sequins.

1 . 2

One can’t do justice to the contemporary American sonnet in four Sundays, but one must try anyway—-as one must also share the notes of admiration which exist in the margins of one’s preparations. Of relevance: the perfect pro-rhyme position as articulated in “Presto Manifesto” by A. E. Stallings. For background on the 18th century sonnet, a book chapter. For sheer beauty, see Monica Youn’s breakdown of the Petrarchan sonnet and Milton in this excerpt from Blackacre. For sonic and structural subversions, see Candace Williams’ “Gutting the Sonnet: A Conversation with Jericho Brown” and Stephen Kampa's thoughts on "disguised form" and "echo verse" sonnets. For details on turns and motions, see Michelle Boisseau’s “The Dancer’s Glance” and Virginia Bell’s “The Turn as Poetic Striptease in Anne Carson’s ‘Wildly Constant’.” For a close look at Gerald Manley Hopkins and the curtal sonnet, see Haj Ross’s "How Hopkins Pied It". For anything and everything, see Mike Theune’s labor of love: Voltage.

1. 3

The texture of Anne Boyer’s archival sonnet notates itself in demise, as something which perishes and can (at best) be preserved. One thinks of the 19th century Atheneum group’s desire to manufacture ruins, or to create the ruined form of the substantial and monumental.

A Sonnet from the Archive of Love's Failures, Volumes 1-3.5 Million

by Anne Boyer

If you were once inside my circle of love

and from this circle are now excluded,

and all my love's citizens I love more than you,

if you were once my lover but I've stopped

letting you, what is the view from outside

my love's limit? Does my love's interior emit

upward and cut into night? Do my charms,

investigations, and illnesses issue to the dark

that circles my circle? Do they bother

your sleep? And if you were once my friend

and are now my villainous foe, what stories

do you tell about how stupid those days

when I cared for you? Because I tell stories

of how you must tremble at my love's terrible walls,

how the memory of its interior you must always be eroding.

The poem begins in the conditional— “If you were once inside my circle of love”— and sets this part as a single-line stanza so the reverb can reach down into each stanza separately. The stone-swoon internal rhymes of the second stanza, after the sharp enjambment—“my love’s limit? Does my love’s interior emit” —- reveals how splendidly the shorn word makes for a rhyme. It’s as if the limit got clipped, a bit of Samson and Delilah energy.

Kevin McFadden on sonnet: it has the "dramaturge's urges, it wants to talk itself out..." One feels this dramaturgical urge in the questioning of Boyer’s sonnet, in the trembling of “love’s terrible walls.” Ruination is the point as well as the momentum.

1. 4

Will teach Bernadette Mayer’s “Sonnet”—- every time I re-read it, the sonnet rises from the ruins of a skyscraper, insisting on being seen while forsaking everything except the patina of its form. But there is a building, and there are techniques which helped create it. Among Mayer's plays, notice the mixed references to pop culture near ancient history— G. I. Joe and Cobra Commander nestle near Catullus. Mayer does this with diction as well, so we have the high of "soporific" and the low of "fucking." Another play involves using found language— "to _____, turn to page___" comes from Choose Your Own Adventure books as well as women's magazines and instructionals. The Choose-Your-Own-Adventure vibe of the extra couplet is as modern as a sonnet can get. It's as if Mayer wants to suggest the sonnet of the present advertises a choice rather than a conclusion or an argument. It ends in an option. Or the illusion of an option.

1. 5

Voltas. The volt. The surge or the bolt. The position from one which one can pivot. William Matthews named it the “invisible hinge” in his poem, “Merida, 1969”, where a major change in content (or form) occurs across a stanza break. The poem doesn’t comment on the shift but absorbs it. Also called a “pivot” or a “dovetail joint.” Forrest Gander calls the volta the "argument turn." H. L. Hix has 12 questions about the turn.

1. 6

“Language is just music without the full instrumentation,” says Terrance Hayes. The musicality of the sonnet, particularly in the Petrarchan’s relation to be written for singing and scoring. Sonnet as a form which invites the imagined symphony into the texture. Instrumentation is figurative language and figuration, I think. One can bring various instruments into the poem, and maybe this is a more interesting way of thinking about “voice” in poetry—-or in the voices brought into a poem. The association of voice with Iowa-style, US ‘confessional’ poetry makes it difficult to discuss the vocable and vocalizations of poems: everyone presumes the voice is personal, and that they are developing their voice?

Elsewhere, Hayes on wearing multiple shoes and taking multiple paths:

“I have very little interest in establishing a fixed style or subject matter.… I’m very interested in wearing Larry Levis on one foot and Harryette Mullen on the other. Or on another day—in another poem—Gwendolyn Brooks and Frank O’Hara. Reading provides an infinite number of shoes and paths.” (Italics mine)

1. 7

American Sonnet for the Magic Apples

by Terence Hayes

Or the one drunken half-quarter grand uncle recalling

The sound speckled apples on his fabled real daddy’s

Coastal orchard made falling multidimensionally

To the vaguely salty combination of plantation dirt

And marshland bearing the roots of this strange

Distant cousin to the plum, the Cherokee palm tree,

And West African pear, color of a bloody, dusky, ruby,

Husky & almost as bulky as the lamenting lamb’s head

His daddy lopped off once & kicked at him laughing,

The uncle informed me wistfully at a reunion of family

Fleecers, fabricators, fairy tellers & makeup artists

With his cast-off awful alcohol stench burning my nostrils

As he gripped the back of my head & gazed deeply

At the speckled invisible apple or head in his hand.

The specificity and sonic entanglement of Hayes’ diction strikes me. The way plum draws into the palm of the first line… The way sound serves as integument … and the proliferation of y-endings… bloody, dusky ruby, husky … bulky—which then leaps into the lamenting lamb’s head and the lopped of the next line. Hayes is the maestro of strung-sonic-effects in the contemporary sonnet form.

In an interview with Lauren Russell, Hayes had the following to say about “the perfect poem”:

If you think about an animal, there’s no perfect animal. Most people think of poems like they’re machines. I’m thinking of something more organic and human that exists the way it needs to exist, more like a baby or child. How do you achieve that? I think of myself as a person who likes to be in control of everything. So how do I surprise myself? For so long I’ve been this person who’s been too in control, so how do I relinquish control? Some of it’s about line breaks, narrative. I like the poem to look a certain way in terms of line breaks, but how do I release control? Some of it is subject matter. The poet wants to be liked in the poem, but what does it mean to not always chase some kind of appeal? Discomfort, vulnerability, rawness that come up in a poem—that also has to do with perfection, the absence of perfection. That’s hard to teach, but if you make people more generous in the workshop, then you can get it. You say, “Oh, it’s not a perfect poem, but it’s pretty good; we’ll take that.” It creates generosity if you aren’t chasing a perfect object.

Refrain: It creates generosity if you aren’t chasing a perfect object.

1. 8

The game-like structure of Hayes’ essay on poetic lineage—the cards which trace influence, and challenge the simple directionality of influence we tend to read into pedagogy. I keep thinking of riffing and jazz and blues, the performances that depend on multiple variables, none of which can be easily isolated. The piece plays you; and you play the piece—and one is played by it.

1. 9

Past conditional tense is a form of privilege wielded by the present against the past.

Julian Barnes’ description—- “What mother would have wanted…” a hypothetical based on a person who lived and now doesn’t. A double-remove prone to projection.”

"The silence was so intense there might have been a sound moving around in it." (John Ashbery, Girls on the Run)

1. 10

Sunday Service

by Taylor Byas

“The Blood Still Works” stampedes through the nave

and once the organ player’s shoulders seize

with song, the spirit hits the pews in waves.

I catch the loosening necks, the mouths’ new ease

as the congregants begin to speak in tongues;

I move my lips, pretend to be saved, and next

to me, my grandma convulses—-the drums

of the band a puppet master, a hex—-

while ushers in white surround her, lock hands

to keep us in. The preacher’s sermon builds

to a screech, his sinners flitter fans

like mosquito wings, and with his eyes he guilts

me into clasping hands: I repent for things

I’ve yet to do. They jerk to tambourines.

Mike Theune on “strange voltas”— and how the “heat map” of the poem makes the volta glow. This Shakespearean sonnet enlivens the rhyme scheme with off-rhymes and slant rhymes— and I wonder if that is why Byas’ writing feels so fresh, so unexpected, so vivid. The subject is glossolalia—-or speaking in tongues. For those who haven’t observed it, the effect can be jarring: one doesn’t know whether the person is literally seizing or experiencing an ecstatic connection to the divine. Byas rides that margin between ecstasy and neurological misfiring throughout the sonnet. Lines like “his sinners flitter fans” and “with his eyes he guilts” are incredible—-as is the held breath enacted by the stanza break, the bigness of that enjambment.

1. 11

The eros of sparse sayings, the statuesque nude statue, as in Richie Hofman’s “The Romans”. I thought of Derek Jarman’s sonnet torsos, almost. But also of how the statue, like the sonnet form, craves its own ruin—or exists as erotic possibility in relation to that very ruin. As in Shakespeare’s Love’s Labor Lost, when Armado, upon discovering that he has fallen in love, says: "Assist me, some extemporal god of rhyme, for I am sure I shall turn sonnet." The extemporal god of rhyme, like the lyric poem, sits outside time; he languishes in eternity.

1. 12

Note on the extraordinary variety of form and adaption in the contemporary sonnet. Amit Majmudar's “sonzals”; Bernadette Mayer’s “deconstructed sonnets”; Molly Peacock's "exploded sonnets”’ John Berryman's "devil sonnets" (which Kevin Young has called the six-six-six); Jericho Brown's "gutted sonnets"; Joyelle McSweeney's "almost sonnets"'; Tyehimba Jess' "shattered sonnets" ; Gwendolyn Brooks' "soldier sonnets" ; Ted Berrigan's "sonnet collages"; Dorothy Chan's "triple sonnets" ; Diane Seuss’ sonnets built from the syllabics of the “American sonnet”; the sonondilla (or sardine) by Charles L. Weatherford; the salamander’s fireburst by Jose Rizal M. Reyes (and, less recently, the Pushkin sonnet by Alexsandr Pushkin).

1. 13

Bernadette M. again: I'm through with you bourgeois boys. The internal rhyme lifts this line from the page; it hovers in the air of the poem like a joke or a threat. Lines move like ruffled feathers or windblown papers, borrowing from collage:

Nowadays you guys settle for a couch

By a soporific color cable t.v. set

How the enjambment thickens "by". Buy a tv set or sit by a tv—it's all the same texture for the boys who got bought by it. Mayer brings her study of Greek and Latin prosody to the Lower East Side of New York City, where the land "of love and landlords" ties the personal to the political. Sometimes it feels as if the speaker is a female Catullus.

1. 14

The erotic cufflinks of the sonnets—the ecstasy where Donne’s holy sonnets meet Simone Weil’s asceticism. And how much tension exists in Mark Jarman’s “Unholy sonnet” series, with their focus on the reasoning mind, and their resistance to extravagance. In The Flaming Heart, Mario Praz discusses the ecstasy Bernini’s Saint Teresa:

There exists in Rome, in the church of Santa Maria della Vittoria, a work of art which may be taken as the epitome of the devotional spirit of the Roman Catholic countries in the seventeenth century. Radiantly smiling, an Angel hurls a golden dart against the heart of a woman saint langourously lying on a bed of clouds. [The Italian name for this work of art is "Santa Teresa in Orgasmo."] The mixture of divine and human elements in this marble group, Bernini's Saint Teresa, may well result in that "spirit of sense" of which Swinburne, who borrowed the phrase from Shakespeare, was so fond of speaking. Spirit of sense as in that love song the Church had adopted as a symbol of the soul's espousals with God: The Song of Solomon, which actually in the seventeenth century was superlatively paraphrased in the coplas of Saint John of the Cross. Inclined as it was to the pleasures of the senses, the seventeenth century could not help using, when it came to religion, the very language of profane love, transposed and sublimated: its nearest approach to God could only be a spiritualization of the senses.

Of Bernini's angel and saint, not all critics agreed with the sacralization of spiritual ecstasy. Mrs. Anna Brownwell Jameson (1794-1860), for example, declared that "all Spanish pictures of S. Teresa sin in their materialism…".

1. 15

Anthony Hecht (who has done his time with the double sonnet) takes Shakespeare’s Sonnet 151 ("Love is too young to know what conscience is") as "the bawdiest-some would say the crudest and most vulgar" of the Bard’s sonnets: "In a comic-erotic parody of the vassal's submission and fidelity to his midons, Shakespeare subordinates his soul to his body, and his body, synecdochically represented by his penis, is made subservient to the mistress to whom the poem is addressed."

Lupercalia (which also happens to be the Day of the Bear referenced in my poem, “On the Day of the Death of the Bear,” published in Copper Nickel last year)— and Hecht’s passage on it:

The Roman feast of Lupercalia, observed on the second of February, was observed as a fertility festival, celebrating both the growing of crops and the sexual vitality of humans and the other creatures. The festival coincided with the resumption of work in the fields after the rigors of winter (which, in Italy, were milder and briefer than in the northern part of the United States). But in the year 492 Pope Gelasius I abolished the Lupercalia, and substituted for it a subli- mated version known as the festa candelarum or Candlemas, dedicated to celebrating the Presentation of Christ at the Temple and the Purification of the Virgin Mary. Its ritual involved a procession of lighted candles meant to symbolize the light of the Divine Spirit.

Followers of Orpheus took the councils of dark, unlighted night as the source of the most profound wisdom. Prophecy comes to those who are willing to risk the world, or to plunge into metaphysical mania, in search of an even more disorienting ecstasy. Or this is the Orphic position’s stake in the saying. Some poets are more Orphic than others.

1. 16

David Haskell wrote what he heard from listening to trees…to green ash, cottonwood, ponderosa pine, redwood, etc. "Sounds travel around and through barriers," he said, so listening to trees "reveals stories and processes that are otherwise hidden." A botanical soundscape formed from small labs of attentive listening.

Nicole Walker: "I also love the form that wilderness imposes on the wild. That hawks must eat baby squirrels. That bark beetles decimate drought-stricken pines. That Max must go home for dinner." [Italics mine. Time as formal constraint in sonnet.]

1. 17

In response to John Donne’s holy sonnets, Coco Owen borrows the key words and leans into the possessive, capitalist/conqueror analogies. “Mocking little purr,” to quote Erik Satie’s tempo marking.

1. 18

A cosmology is an account or theory of the universe. The word comes from French cosmologie or modern Latin cosmologia, from Greek kosmos ‘order or world’ + -logia ‘discourse’. Cosmology is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's Glossographia. Cosmic discourse!

1. 19

"Beneath these stars is a universe of sliding monsters,” wrote Herman Melville.

Slippage is central to cosmology—and to the words selected as stars in one’s sonnet. Always the question of how to constellate them.

1. 20

Not enough time to talk about curtal sonnets or bring in Gerald Manley Hopkins. But I can squeeze in Rimbaud’s monosyllabic sonnet. On the other hand, there is sonnet energy in Johannes Göransson’s “Sugar Theses”— there are strange juxtapositions which could be culled from his words as titles or prompts:

When I’m writing about shoplifting, I’m writing about the divine. When I write novels about sugar and movies, I’m writing about war. I don’t have the proper distance toward art. I don’t believe in minimalism. I’m prone to outburst and invasions. I live in an exocity and I can taste the poisons. I pick playgrounds for my children based on the contamination levels. I pick my children up and stare at them as if they were snakes. My children are snakes. At least in the paintings of the pre-raphealites.

Fourteen lines turns into an addiction. Like a toy you want to ride everywhere just to see how it feels over different terrains.

1. 21

Variations: Clark Coolidge’s Bond Sonnets; “White, White Collars” by Denis Johnson; fraction sonnets like Elizabeth Willis’ “63 ½”; Jeffrey Thomson’s “Blink”, an enumerated, list-like sonnet: Thomas Carper’s “Catching Fireflies,” a sonnet strung from one long sentence; “Nicole Steinberg Brett’s Getting Lucky; a sonnet in a letter from John Keats. The buried-in-a-letter sonnet deserves recognition, I think, as an epistolary sonnet, even if it evades itself by wearing feathers.

1. 22

I keep coming back to Terrance Hayes, particularly when trying to decide whether to push towards use of contranyms and homonyms in sonnet prompts. Contranyms are words with opposite, or nearly opposite, meanings. An example is sanction, which means “to authorize, approve, or allow” and “to penalize, discipline”.

The magic of this in “New York Poem”—-and how Hayes continuously draws in the blue note, the jazz brush, the disco, the music in counterpoint against the “sci-fi bridges.” One could also read this as a declarative (“the sci-fi bridges) rather than a description (the bridges which look sci-fi).

1. 23

John Berryman in “Sonnet 13”, ending the first stanza’s rhyme (glass / brass / pass / alas):

“The spruce barkeep sports a toupee alas—”

The clipped, lexical control of Joshua Jones’ series, “Thirteen Sonnets in Transition.”

The way Marilyn Hacker slips her lesbian love inside a French word in “La Loubiane”:

Two long-haired women in the restaurant

caress each other's forearms. I avert

my eyes. I'm glad to see them there; I hurt

looking on, lonely, when I so much want

to touch your arm, your hand like that, in front

of two mémés enjoying their dessert

And the way Hacker begins an untitled sonnet with the line: “First, I want to make you come in my hand”.

1. 24

francine j. harris’ sonnet uses the wetland as an extended metaphor in an address to a lover or former lover or a lover somewhere between solid ground and open water.

Wetland

by francine j. harris

The sea is so far from us now. Partly I think because we

are not softspoken desire. There are rude thoroughfares

and abandoned mines that brag. They gather and pile

with ruin and vacancy. It's an accrual that is in me, it seems.

At best, a wetland. Beautiful and useless in the face of flood.

So that when we walk the perimeter, we can see the ground

starve and crack. But then fear of sinkhole is so important.

Truthfully, I am not enough to steer clear of. To fall in love again,

dear, reforested bund, is a matter of self-preservation. In your expert

opinion, will you tell me how to know you if I am forever meant

to leave you undisturbed. This will not save us, I'm afraid. A brownstone

for hummingbirds is shortsighted too, like picking out honeybees

from the dog's mouth. Then blowing on her tiny hairs like a breeze.

Love, we can wish it were so; it does not make us fit to survive.