The surrounding arches of the domes located in the Hagi Sophia include mosaics of hexapterygons, the six-winged seraphs said to surround God’s eternal throne. To be so utterly wing-limbed in all directions seems fantastic, and there is this space in contemporary liteature where the fantastic supernatural meets science fiction. . .

“Backfictions”

Antoine Volodine is the primary heteronym used by a Russian-French writer and translator who won the French Grand Prix de l'Imaginaire, a prize usually awarded to science-fiction writers. Like Fernando Pessoa, Volodine makes use of multiple heteronyms (see Lutz Bassmann, Manuela Draeger, Elli Kronauer, etc.) to author his books. Like Guido Morselli, Volodine's books are often classified as speculative fiction or sci-fi. But, according to the writer himself in 1991, his writing could be called "Anarcho-fantastic post-exoticism." They—Volodine and his heteronyms— have published over 40 texts of what he later narrowed to "post-exoticism," the genre invented to publicly break the boxes literary critics tried to fit them inside.

“We are several authors, we are writing from an elsewhere that is in a prison, we are composing a foreign structure entirely out of texts, we all share the same egalitarian and revolutionary ideology, we are reclaiming a poetry rooted in equal measure within shamanism, bolshevism, magical realism, and oneiricism,” Volodine told Jeffrey Zuckerman and JT Mahany in a 2015 inteview, which also happens to be one of the most abundant resources I’ve found on Volodine, as conducted by Zuckerman, who is likely his most astute contemporary reader.

So Volodine tells Zuckerman and Mahany:

Most of our narrators have a shamanic way of telling stories. They speak to evoke history, but they also create characters to go with them, or instead of them, down the difficult path of fiction, their painful path toward memories, toward the present, or toward black space. Narrators assume this somewhat priestly function, and in this way, they don’t just tell stories, they also live them. Entering a post-exotic anecdote or image is often accompanied by a trance. The reader doesn’t simply watch a story—passively, objectively—he or she is invited to plunge into the image, into a cinematic succession of images, to psychically and maybe physically accompany the shamans who speak, repeat, and sing the story.

For these notes, I limit my digressive sally to Volodine’s novel, Minor Angels, as translated by Jordan Stump (University of Nebraska Press, 2008).

The Problem of Angels

I did not expect to fact-check angelology while reading this novel. Nor did I anticipate returning to the energetic relationship between constructions of free will and the pedagogies of neoliberalism. Yet there is a sense in which the difference between angels and demons hinges on this construction of loyalty to something larger, something divine that subsumes the self while eventually fulfilling it, or giving life meaning. There is this mystery in the fullness of time etc. * And there is the social significance of loyalty, a word that simulatenously defines and monitors our affiliations and creates notions of worthiness. We track loyalty’s tempo and meter the measurement.

In return for affiliative self-knowledge, the loyal pledge their allegiance, or fides, through the performance of declarative displays. As a ceremonial action, the rituals of fealty provide the believer with a community, a sense of belonging, and the possibility of t-shirt or branding device that announces this allegiance. Our loyalties simultaneously mark us and demarcate us from others. Contemporary brands have expanded these sources of community to include corporations (the war between Pepsi and Coke, etc). Experts on affiliative properity emerge to decode the affects and gestures. Markets provide expertise in everything from pore-size to perfect parenting. Late capitalism has made this so normative that we hardly notice—unless we are seeking kinship. *

As for the angels, muddled loyalty was their undoing. Unclear allegiance got them expelled from the kingdom of heaven and, later, the ecclesiastical canon. Early religious leaders knew that angels and demons were kinned, as reflected in monastic writings and illuminated manuscripts. The growth and expansion of religious institutions (i.e.bureaucracies, armies, institutions) made taking sides imperative (one can't very well ride both sides in a war). To serve heaven or hell is the final question. To question is the final question is to deny Christ. The “you’re either for us or you’re against us” binary complicates the the Pascalian wager of playing the field.

Set in post-apocalytic end-times, Minor Angels locates itself outside linear time. The last humans (and there are many) seek to keep the dying world through "revivification or revolution or simply through acts of memory," in Jordan Stump's description.

The pseudoapocryphal aura emerges from references to original book or revelation, a sort of subtextual dialogue with the idea of the “one true story”. Volodine’s fictional spirit-worlds blur the distance between embodiment and living. He is emphatically not a Christian. His theories of time and embodiment borrow from Tibetan Buddhism. His references to Bardo Thödol are accompanied by the claim that the Tibetan Book of the Dead is the putative Bible among prisoners, the single non-post-exotic text shared between the writers incarcercated in his stories. His interest in shamanism tiptoes round the rims of Mircea Eliade’s shamanic neo-paganism.

Do I parse Volodine’s beliefs because I sense the stirrings of a belief system in the novel? Am I curious about how paganism plays out with multiple creators dressed up as authors? The is a disconnect reminiscent of my failed efforts to see the magic in the autostereogram, or the hours I spent failing to spot the shapes in those psychadelic mall posters —- and that feeling of abandoning the promised epiphany, which may be another way of wondering if the disconnect is in my vision rather than the object it attempts to understand?

One creature on my shoulder says apocalypse is not possible without the presumption of linear chronology, the belief that all things are moving towards an end; a similar creature on my other shoulder says a world in which apocalypse is insignificant must also be a world in which historical Progress, itself, is challenged by post-exoticism's commitment to narrative polyphony and non-linearity. From where I stand, doubly-creatured, there is no mirror, no revelation. I don’t know which one is the angel and which is the demon. I suspect both are both, and distraction is immanent.

The Problem of Time as Encountered in Form: Anecdote v. Narract

Volodine (and the others) would abhor my attempt at synopsis. He would urge me, instead, to focus on how our understanding of time reflects what we want from it. And what we want matters: the skin between desire and temporality is central to Volodine's project.

Time, desire, etc . . . the forms language gives us for wanting. The words my child just used to express a desire for food located in the near future where it is the idea of nearness, itself, that remains in dispute. My near-enough is her far-away, just Volodine's angels are present and simultaneously past. Apocalypse has happened, is happening.

Volodine’s time-sprawling narrative occurs in a Bardo-tempo, where a group of immortal crones consigned to a nursing home plot their revenge on society which forgot them. These crones were once revolutionists, and their hunger for revolution leads them to create a son, Will Scheidenmann, from discarded fabric and dust mites. Because a life patched from the refuse of poverty, fury and resentment will be vulnerable to pleasure, power, immediate gratification, Scheidemann is seduced by capitalism, entrepreneurship, and consumerism. The crone-mothers are furious—they brought capitalism back to life by concocting a son—and so they reclaim him, dragging him back to the yurt of his birth, where, like Scheherazade, Scheidenmann delays his punishment by reciting one narract a day.

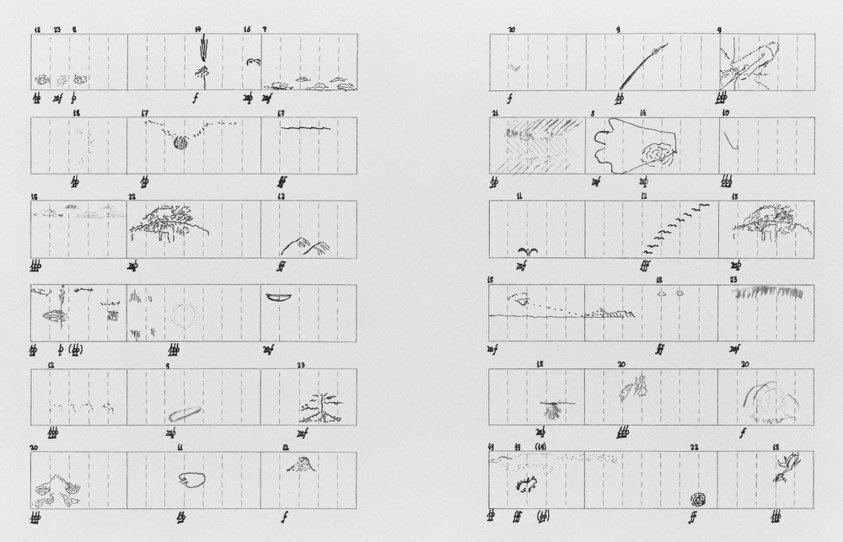

One narract a day makes a collection. Scheidenmann’s "narracts" present themselves as narrative acts of resistance. Each one is named after the angel who narrates it. And each angel communicates in the post-epiphanic narract form, creating an iconography of unstable characters, each of whom is listed in an index of 49 minor angels at the end, after having "passed through our memory, one per narract."

The formal anti-modernism built into these divine sequences distinguishes them from anecdotes, a form which has moral ballast, or weight, built into it. Volodine himself, has made this comparison, saying the narracts are "something other than limpid, artless little anecdotes." This other than includes images intentionally constructed and informed by dreams, received images. (Yes, Mark Fisher’s theorizing comes to mind.)

If Rene Char’s description of the anecdote as a tale with moral ballast, or expectation, built into it, then Volodine asserts the narract's focus on aesthetic longing against that moral ballast. In Volodine's words, these are "something other than limpid, artless little anecdotes;" a narract is a vignette which "captures a sitation's conflict...between recollection and imagination" by leaning on "poetic sequence" for its structure and organization, informed by dreams and received images. Informed by dreams and received images, the narract is delivered in shamanstic fashion, enabling its speaker to embody the past rather than return to it. Conceptually, the narract neologizes narration to the act of narrating, so that the narract becomes the story's embodiment.

Traces Between Translations

Each of the forty-nine "prose moments" is marked with "the trace left by an angel"— not as a savior but as a witness to each "place of exile” where those whom Volodine remembers and cherishes "go on existing as best they can".

We see this in the first narract, where the narrator speaks from inside a ruined time. Although this speaker is sad (thus seeking a "tear-fixer") his words are addressed to a Thou-like You, someone he thinks about often, and it is this thinking, itself, which seems worthwhile. The first speaker extols longing as a worthwhile form of action, a radical act at a time when we are measured by resumes, numbers, and achievements.

Longing achieves nothing, and yet, it acts on the mind in ways that leave traces. Narraction challenges the angels’ relation to endings.

Fred Zanfl is a writer who depicted the end of the species, a man who survived the coups and who refused to accept his own ending or death. Zanfl rejects extinction as "a fictive thing because it had never been described from within the mind of the one experiencing it. "I will stand on the railway of my death," Zanfl writes, in a narract which ends:

I have carefully written these words. No matter what happens, let no one be blamed for my life.

Having used Marguerite Yourcenar's line "Let no one be accused of my life” as an epigraph, this last line (“let no one be blamed for my life”) struck me as an example of what Volodine has called the "anonymous intertextuality" in the post-exotic process. It is as if he allows Zanfl to overnarrate Yourcenar, with a slight modification.

Whereas Yourcenar asks that no one be accused of, or indicted for, her life, Zanfl asks that no one be blamed for it. If Zanfl is infected with Yourcenar’s traces, it is because Volodine wants a dialogue with the absent. The declarative "I" stands fully accountable; it disrupts the fatalism implied in Yourcenar's comment.

For contex, the line being translated from Marguerite Yourcenar's Fires, is: "Qu'on n'accuse personne de ma vie." To some degree, the semantic distance between blame and accusation is smaller in French, and one can't help wondering if these two lines resemble each other in their untranslated form. Tant pis, I lack a copy of Volodine in French, though I wouldn't be surprised if he plays in the present indicative tense.

The Part Where the Clock Struck Twelve

At 12:15 am on a Monday, one could read Volodine’s narracts as ruined revelations.

"Every finished work is the result of a collective creating," Volodine has said, and this multiplicity blurs a single authorial meaning.* Minor Angels doesn't intend to generate meaning within the reading experience itself (meaning arrives in the dreams which result from the reading), and much of the action takes place outside the frame. This way of looking at reading resembles a scripture, or an apprenticeship to revelation. It also indicts my present attempt to interpret it. All the more reason for me to continue it, tomorrow.

Unpursued Traces of Interest; a.k.a. end-notes

“In the fullness of time, etc.”: The thicker and more foundational our conception of free will,” the more cosmological and eternally-serious our conception of loyalty?

“Markets provide expertise in everything from pore-size to perfect parenting. Late capitalism has made this so normative we hardly notice—unless we are seeking kinship.”: I wear my declarative feminist t-shirt to flash a virtue-signal towards the like-minded (i.e. to find my people) and to assess the responses of others (i.e. which I interet as friendly or threatening).

Translators J. T. Mahany and Jeffrey Zuckerman described the uncanny similarities of their introductions to Volodine: “We both discovered Antoine Volodine, appropriately enough, in winter. One of us was sitting in a classroom overlooking bare trees, translating the first pages of Des anges mineurs. The other one of us had just read the same novel in English and was sleepwalking through the dark, snowy streets of Rochester recalling Volodine’s declaration that the novel’s meaning was “not in the book’s pages but in the dreams people will have after reading it.” See also Antoine Volodine in conversation with Jeffrey Zuckerman, Paris Review (July 8, 2015), where J. T. Mahany and Jeffrey Zuckerman call Volodine’s books “almost as dreamlike as their author himself”:

He writes under four (or perhaps five) heteronyms, including Antoine Volodine, and only the most basic facts of his biography are known: he was born in 1950, came of age during the 1968 student protests in Paris, and taught Russian in France for some fifteen years before devoting himself entirely to writing. His debut, Comparative Biography of Jorian Murgrave, appeared in France in 1985. It is the story, told by way of fragmented microbiographies, of an alien hunted down on Earth whose dreams are invaded by psychobiologists intent on making him talk. “There is no way I could call Biographie comparée a novel,” one befuddled critic wrote; others were swift to express their shock and delight at such an innovative author appearing in the frequently monotonous ranks of science fiction. In a matter of years, Volodine had became famous for his (and his heteronyms’) singular brand of writing.

“…blurs a single authorial meaning”: I thought of scriptures, sacred books, the texts against which heresy is defined and punished—-and how the multiple authors of scriptures are taken as one speaker — and how this single meaning is also disrupted at the level of interpretation and embodied retelling.