1

I am watching the wind and wondering if we’ll lose power on this wild weather day in Alabama. Schools are closed. The house is filled with music and the energy of my restless teenagers whose disgruntlement has its own wind—- a wind I fear and respect and know well. A wind that wants something from the mountain.

Distracted by a tweet that drew me back into the vortex of Celan, the mountain is present. I learned yesterday, on twitter, that John Keene had played with translating “Todtnauberg” on his blog, and I quote Keene’s thinking-into that process below:

The entire poem feels this way, almost a bit dizzying, a record of—-what?—-a visit, but also a revisiting, a trip to the Death Mountain ("Todtnauberg") which leaves its grief-mark like the burst of the beautiful and haunting healing flowers'' names, "Arnika, Augentrost," or those ominous "star-dice" on the well's head—-in part, as this poem.

A wind gust just knocked a small stone statue off a table on the porch. The sound of it shattering vacates a brightness, a sonic star-shape that represents an absence. Irresistible: the shiny music glass makes when we break it.

“The wind is not to be underestimated,” I tell the teens who are making weird sandwiches in an effort to outdo one another in weirdness. The point at which the weird morphs into the grotesque is the narrative suspense-engine of weird-making. The point differs with each medium, each material, each subject. The weirding-game must be played for effect repeatedly.

2

I’m thinking about Anne Carson’s poem, “Todtnauberg”, featured in the current issue of Poetry Review.

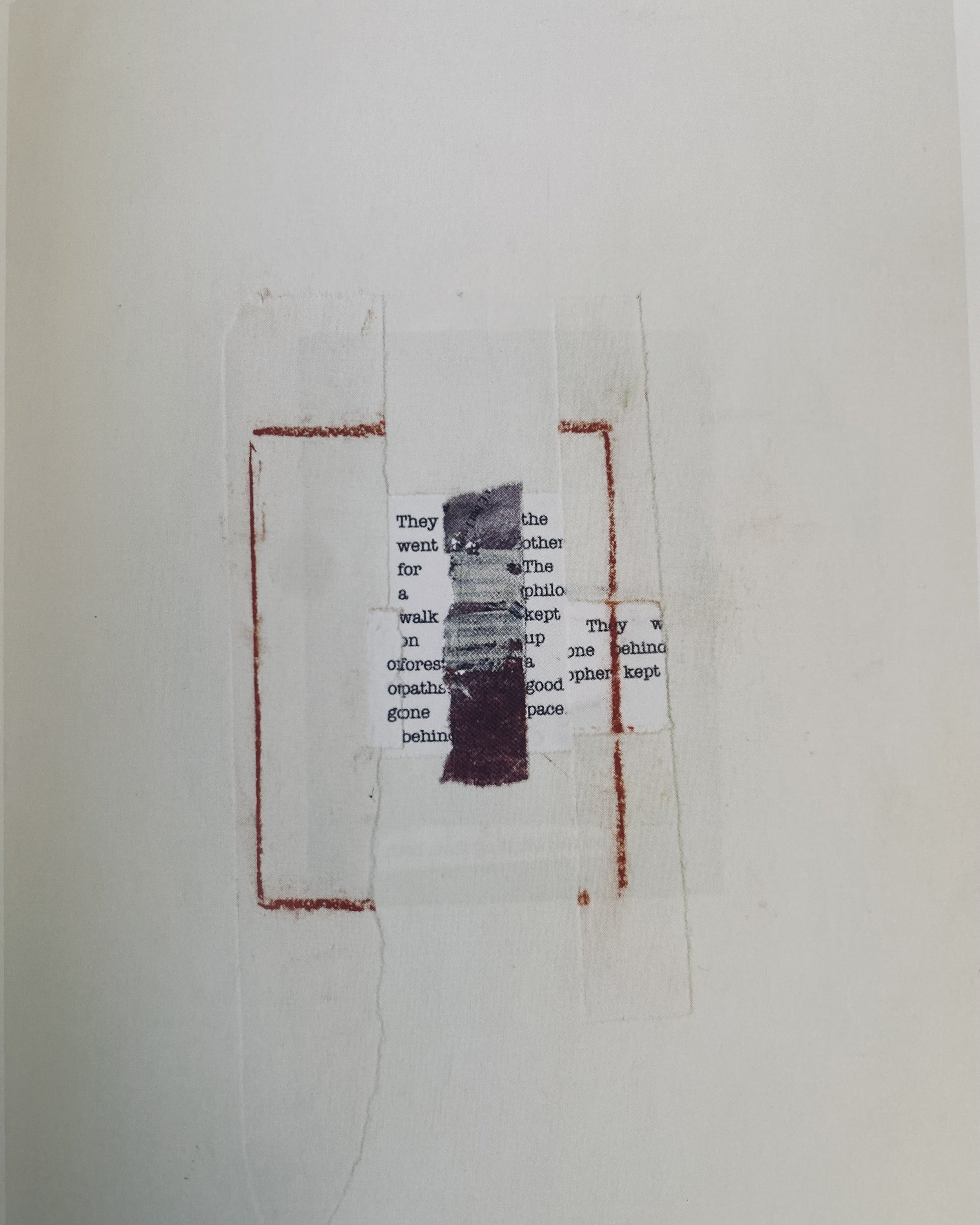

Despite the absence of Celanian language and its collaged form, I’m tempted to read it as a translation of Celan’s own “Todtnauberg”. After all, Carson has used translation to rewrite and destabilize various classical texts.

3

I’m going to leave the failed encounter between Heidegger and Celan to the poem. Come with me, as it rains, to a different mountain. A different encounter that failed to transpire.

In July 1959, Celan went with Gisele (his wife) and Eric (his son) to Sils-Maria in the Swiss Alps. Theodor Adorno was supposed to be visiting at the same time, and Celan hoped to meet him and speak with him.

For reasons that remain unclear, Celan returned to Paris early and missed encountering Adorno.

One month later, in 1958, he wrote his only (?) German prose fiction, "Conversation in the Mountains," addressing Adorno's refusal of poetry after Auschwitz. It also drew on Kafka's story, "Excursion into the mountains," written in 1904, which Celan had translated into Romanian after the war.

John Felstiner thinks the story owes most to Martin Buber's "Conversation in the Mountains", with its focus on the I-Thou encounter and relationship. A prototype was the novella, Lenz, by George Buchner, which Celan also referenced in his Meridian speech for the Buchner prize in the following year:

On the 20th of January Lenz went walking through the mountains, where he wanders in search of something, wrestles with lightning like Jacob, and hears a voice in the mountains until madness overcomes him.

Lenz declares himself the "Wandering Jew, and asks if people don't hear "the horrible voice" that we "customarily call silence". Celan remembers Len and his story with "its roundabout paths from thou to thou... paths on which language gets a voice, these are encounters." Ultimately, these encounters with Others, these conversations with ghosts in the mountains, provoke self-encounters for Celan. Much as he encounters himself in Mandelstam's poems and the act of translation, inspired by Mandelstam's essay "On the Interlocutor."

Few have ventured to go to the mountains and translate the burning bush. Not to receive the burning bush but to translate it on its terrain, into a presence that risks blasphemy, as Celan does after the Shoah in his relentless questions, revisitings, interrupings, on the way to the self that arises in the encounter itself. And here is how it begins:

One evening the Sun, and not only that, had gone down, then their went walking, stepping out of his Cottage went the Jew, the Jew and Son of a Jew, and him went his name, unspeakable, went and came, came shuffling along, made himself heard, came with his stick, came over the stone, do you hear me, you hear me, I'm the one, I, I and the one that you hear, that you think you here, I and the other one – so he walked, you could hear it.....

With the symbols of stone and the crypt—-the way the cryptic actually refers to crypts in Celan:

So the stone was silent too, and it was quiet in the mountains where they walked, himself and that one.

Celan wrote another poem after the trip to the mountains that prompted his prose piece. It is one of his first untitled poems, and it begins what would later be his next collection. It is titled "There Was Earth Inside Them" —- and I will return to it elsewhere, or it will return to me perhaps.

4

In a letter to Celan on August 5, 1959, Ingeborg Bachmann wrote:

I really only see a danger in the ‘hearable’ Frankfurt, for it is in such cases, where the suspicious elements are not so obvious that one becomes entangled with them.

She is referring, among other things, to her dissertation, Heidegger’s festschrift. Martin Heidegger, who was turning 70 that year, had requested that a few of Celan’s poems be included in his honorary festschrift. Celan’s response to Bachmann came 5 days later: he said that his work had been anthology honoring Heidegger without his consent, therefore he did not want to be a part of it.

Out of loyalty (and perhaps love), Bachmann would eventually follow suit. Heidegger’s failure to condemn Nazism— his refusal to denounce the mass killings of the state apparatus which paid his salary—was untenable. Writers were divided on this: Rene Char, for example, allowed his own writing to appear in Heidegger’s honor.

An increasingly embittered and harrowed Celan indicted his disloyal friends. The Goll affair had alienated him from community. More than ever, friendship meant loyalty, and loyalty demanded refusing to associate with persons who maintained the edifice of silent anti-Semitism. Heidegger’s “Hutte” maintained itself in relation to the silence of not-saying.

5

On January 26, 1949, Paul Celan sent a letter to Ingeborg Bachmann apologizing for his silence, asking her to write "to him who always thinks of you and who locked in your medallion the leaf you have now lost." Celan refers to his "brother," a second "him," the one she knows, an underlined "him" he hopes she will not keep waiting.

It calls to mind a lover’s discourse — i.e. if I were a different man, if I were my brother, I would ask you to move here and be close, but I am this man and not the other. There is a splitting, a division within the speaker, that Celan acknowledges. Bachmann picks up this thread in her response to him on April 12, 1949:

I am not speaking only to your brother; today I am speaking almost entirely to you, or through your brother I am fond of you, and you must not think that I have passed over you........ I am trying not to think of myself, to close my eyes and cross over to what is really meant. We are surely all under the greatest suspense, cannot break free and take many indirect paths. But it sometimes makes me so ill that I fear it might one day be impossible to go on. Let me end by telling you - the leaf that you placed in my Medallion is not lost, even if it has long ceased to be inside it; I think of you, and I am still listening to you.

(Italics mine.)

The poet wants to be heard more than seen somehow. There is a certain level of attentiveness that Celan asks of the encounter between the poem and the reader, as well as the poem and its ghosts.

5

Earlier, I quoted from the Meridian speech of 1960. Now we are going back in time by two years. The Celan who is speaking has not attempted to meet Adorno on the mountain. The Celan who is speaking defines attentiveness by quoting Nicolas Malebranche from Walter Benjamin's essay on Kafka, noting that attentiveness is the natural prayer of the Soul. *

In his 1958 Bremen speech (as translated by Rosmarie Waldrop), Celan mentioned Martin Buber by name. He continued referencing authors and texts, continuing his conversations with them. In speaking between quotations, Celan enacted the intertextual relationship of the 'encounter'. As late as 1964, Celan was still thinking about attention. That year, in a letter to a friend (as translated by Pierre Joris), Celan wrote: “Attention is, according to a phrase by Malebranche that you will also find quoted by W. Benjamin, the natural piety of the soul.”

But, back to Bremen: Celan recalled Buchner, the visionary 18th century poet who wound up going mad, and whose novella, Lenz, begins:

On the 20th of January Lenz walked through the mountains... only it sometimes troubled him that he could not walk on his head....

Celan added, "Whoever walks on his head, ladies and gentlemen, has heaven in an abyss beneath him." He said that heaven's abyss accounts for the poem's obscurity.

In what may be a veiled reference to the Wannsee Conference breakfast of January 20, 1942, where the Nazi leaders decided to implement the Final Solution, Celan also said:

Perhaps one may say that every poem has its 20th of January inscribed? Perhaps what's new for poems written today is just this: that here the attempt is clearest to remain mindful of such dates?

Celan’s Bremen-based definition of poetry is "that which can signify a breath-turn"— a breathrun made visible in the poem, "Psalm," which Celan wrote shortly thereafter. "Psalm" is an anti-psalm, or a benediction, a doxology, a prayer written over an abyss. I wish I had time to write more about it, but life leaves so little between things.

Another interesting thing about Bremen is that Celan, perhaps for the first time, speaks about the way “homelands” enter his poetics:

The region from which I come to you – with what detours! but then, is there such a thing as a detour? - will be unfamiliar to most of you. It is the home of many of the Hasidic stories which Martin Buber has retold in German. It was - if I may flesh out this topographical sketch with a few details which are coming back to me from a great distance - it was a landscape where both people and books lived. There, in this former province of the Habsburg monarchy, now dropped from history, I first encountered the name of Rudolph's Alexander Schroder while reading Rudolf Borchardt's 'Ode With Pomegranate'......Within reach, though far enough, what I could aim to reach, was Vienna. You know what happened, in the years to come, even to this nearness.

The dead are those who have not lived long enough to betray the poet.

Celan’s poetry reconfigures the turbulence of what we call “the retrospective gaze"—- a gaze that pretends one can look back without altering the subject being seen. The before/after of therapy often rides on this saddle, this linguistic apparel that tames the past and makes it “examinable.” One senses that Celan cannot forget the chaos in European Jewish communities as information about the concentration camps seeped to the surface. Each attempted to navigate the crevasse between hope and despair: the horrific new information coexisted with the polite denial and surprise of their friends. (“Germans are civilized: they would never do anything so barbaric.”) This is the story of power and ethno-states: we cannot believe them. We cannot believe that people who look like us and sound like us would do such things. We cannot believe we didn’t see what was happening as it happened.

6

Bernard Welt PARODY: This is a big theme in Wim Wenders’ documentary about Anselm Kiefer, with film of Heidegger and Paul Celan’s voice reading his poetry.

Ewen Cameron: Yeah Arendt's book doesn't apply well to Eichmann, but rather Heidegger, as Tuchman posited. He is the banality of evil. Arendt was enamoured with him and wrote a sideways apologia. Eichmann was many things but not banal.

Christopher Satoor: Reading this made my heart drop ..." Heidegger lacked all civil courage" for me his silence on the horrors of the holocaust attest to his guilt, he may not have killed anyone but he used his prestige as philosopher to allow the NSDAP to poison the students at Frieburg.

Jeffrey Gross: It’s speech acts all the way down

Postdrillardian Infra-Scholar: pierre joris’ ‘translation at the mountain of death’ is invaluable

7

And so I return to 1959, the year of Heidegger’s festschrift, the year of the failed mountain encounter with Adorno, the year of deepening alienation from Gisele and Eric, which also happens to be the year that Celan’s German translations of Mandelstam were published in Frankfurt.

The book was prefaced by a note on Mandelstam’s poetry. I quote it and leave the rest for another space and time (italics mine):

.. for Osip Mandelshtam, born in 1891, a poem is the place where what can be perceived and attained through language gathers around that core from which it gains form and truth: around this individual’s very being, which challenges his own hour and the world’s, his heartbeat and his aeon. All this is to say how much a Mandelshtam poem, a ruined man’s poem now brought to light again out of is ruins, concerns us today.