“To listen, as well as to look or to contemplate, is to touch the work in each part – or else to be touched by it, which comes to the same thing.”

–– Jean-Luc Nancy, Listening

“Wrong, wrong! Wrong is done to Wozzeck, wrong was seriously done to Berg. He is a dramatist of astonishing consequence, of deep truth. Have his say! Let him have his say! Today he is torn to pieces. He suffers. As if he had been cut short. Not a note. And every note of his was soaked in blood!”

— Leos Janáček, defending Alban Berg’s Wozzeck after its “disastrous Prague premiere”

1

2

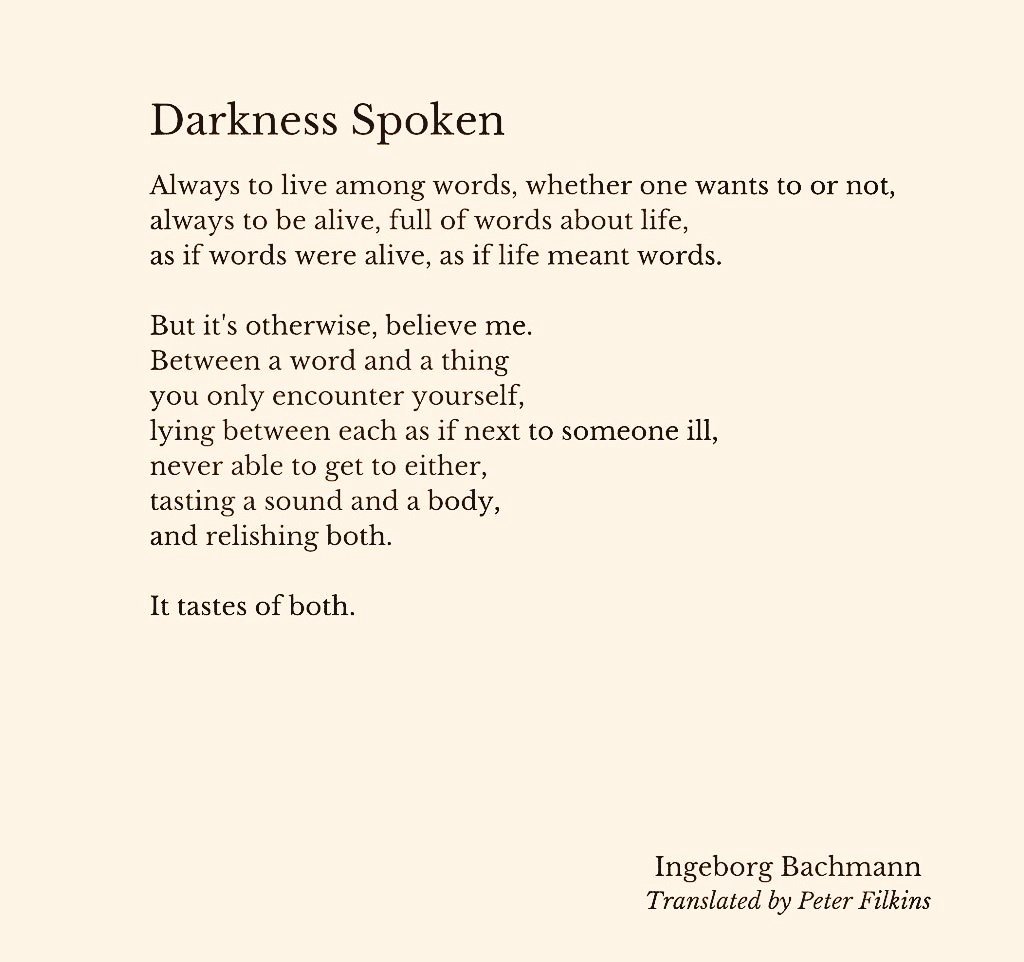

The opening anaphora — “Always” — commits the poem to a time beyond time, a claim of futurity. In the second stanza, the “But” seems to undo this commitment by suggesting we can never really speak to anyone except ourselves. Words, as Bachmann sees them, are useless communicative vessels. Or else: they are things which taste doubly, as sound itself does a thing to the mind.

Reading this poem for sound rather than meaning, I thought of the Greek word diaspon, which is short for diapason chordon (“through all the strings”). Diaspon refers to harmony, or a harmonious combination of notes, and it draws meaning from the Pythagorean system, which holds that the world is a piece of harmony in which man is the full chord.

John Dryden used this word in the first stanza of “A Song for St. Cecilia's Day, 1687”:

From harmony, from Heav'nly harmony

This universal frame began:

From harmony to harmony

Through all the compass of the notes it ran,

The diapason closing full in man.

After providing his song with seven stanzas, Dryden concludes it with a “Grand Chorus” that binds heaven and earth, or the visible and invisible, through chorale. The poem dresses up as religiosity but I think what it does is closer to the spiritual, or that metaphysical plane Dryden occupied. The “Grand Chorus” allows sounds to interpenetrate one another, diluting the sensed distance between one and “an other” in that “last and dreadful hour,” when time itself (that “hour”) “shall devour” “this crumbling pageant”:

The trumpet shall be heard on high,

The dead shall live, the living die,

And music shall untune the sky.

Italic mine. How are we “tuned” towards making music that separates the seen from the felt? How is a poem “tuned”, so to speak, in order to articulate particular images or structure its desires through the deployment of rhetoric?

3

Ingeborg Bachmann’s elliptical dalliance with sound and resonance remind me of a book Michel Leiris wrote later in his life, namely, The Ribbon at Olympia's Throat, which takes Manet’s famous nude for the fragments evoked when studying it. In MIT Press’ description, Leiris’ Ribbon is “a coda to his autobiographical masterwork, The Rules of the Game, taking the form of both shorter fragments (poems, memory scraps, notes) that are as formally disarming as the fetishistic experiences they describe, and longer essays, more exhaustive critical meditations on writing, apprehension, and the nature of the modern.” Like all of Leiris’ work, Ribbon is “rooted in remembrance” and proceeds through wordplay intended to “crystallize” an unstable imaginary as a reality, a truth about the world.

I have always admired the way Leiris complicates the (rather epistolary) text by including an unsent letter that is nevertheless sent by the book’s publication. The letter plays itself as a mask— in a manner similar to Bachmann’s “both”:

4

On that note, two incredible books are entering the world this week— one as a return, the reprint of Montano’s Malady by Enrique Vila-Matas from Dalkey Archive (which I celebrated last year) and the other as a first, Pan by Michael Clune (which I hope to celebrate here next week, if time permits). Both books touch on the difficulty of representation; both eschew representation for experience in their own way; both struggle with correspondences and the interstices between self-recognition and interpretation; both continue to fascinate and provoke me.