According to the 1981 Virago edition, Barbara Comyns “dreamt the idea” for The Vet’s Daughter while honeymooning “in a Welsh cottage lent to her and her new husband by the Soviet agent Kim Philby in 1945.”

Narrated by a girl named Alice Rowlands, a young Londoner who has the misfortune of being born to a cruel, domineering father and a kind, effaced mother who is dying, the novel hinges on a peculiar ability (which some critics have called “the occult” but which seems to me a little off, given Comyns’ own descriptions and references in the text).

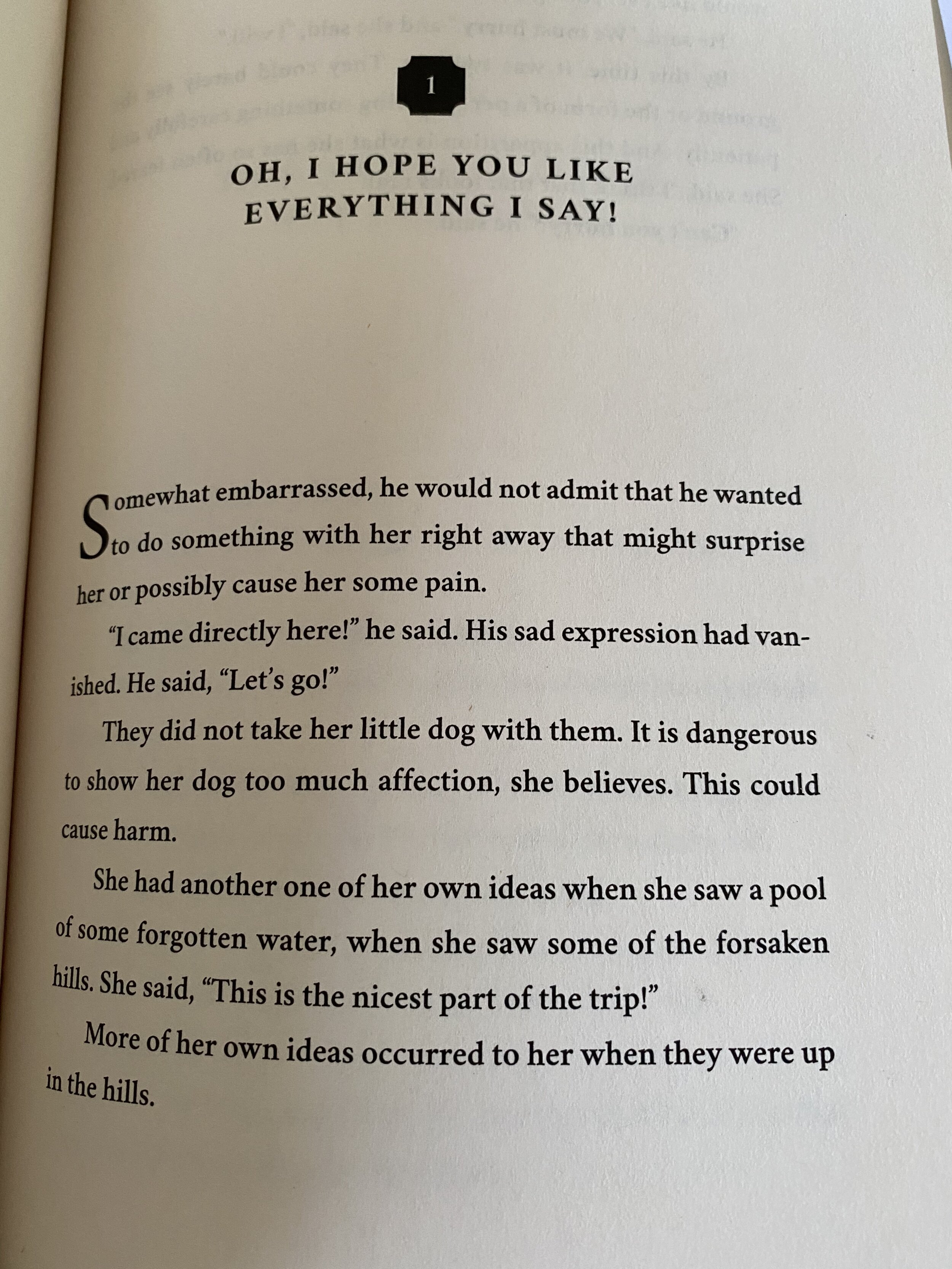

Alice’s father is a veterinarian, so the house is filled with animals, which might seem lovely if not for the reason some humans seem to value possessing animals. In this house —“all overshadowed by my father and cleaning the cats’ cages and the smell of cabbage, escaping gas, and my father’s scent” — one gets the sense that Alice’s mother is classed among the animals by the vet. The third chapter begins:

Autumn came and Mother was still dying in her room. It was peaceful in there because Father was frightened of her illness and never visited her.

Like several historically-powerful megalomaniacs, the father loves animals and hates humans. Or maybe the father loves animals because he has absolute power over them when they come to clinic for treatment, so he loathes humans for having needs and feelings and emotions which he cannot control or fix or end.

One night, Alice’s mother dies while Alice is sleeping, and the daughter wakes up to a world in which her father possibly “put Mother to sleep” with his vet-meds like the animal he took her to be. The suspicion that the father killed the mother renders sleep, itself, unstable — a dangerous, vulnerable state in which one can be destroyed or erased. Although Comyns doesn’t have the narrator express this directly, the way she allows is to emerge is a testament to her narrative skill. The author tells a story that haunt abstract states as well as objects.

“Awake and floating….”

Three weeks after the funeral, the vet returns with a young, “bawdy” gal-pal (Rosa Fisher) who moves into her mother’s room. Comyns sets Rosa up as a type — a certain femme whose currency is male attention, and who over-invests in cruelty, stupidity, anything that placates insecure men. When Rosa’s head waiter colleague, Cuthbert, says Alice is attractive, Rosa expresses sudden interest in the vet’s daughter. Eventually, she convinces her to go out for tea at a nice restaurant, where Cuthbert pays a surprise visit. The three go for a walk — Alice is terrified — and eventually it ends with Cuthbert raping her as Rosa looks on.

Girl power is exhausting, and sisterhood, here, has the synthetic feel of a frat party. After Rosa sets Alice up to be sexually assaulted by Cuthbert, Alice goes home and tries to deal with the feeling that no water will ever render her “clean again.” But that night, after the rape, something strange happens: Alice discovers herself “awake and floating” through the room, holding a glass globe and trying not to break it. She falls asleep peacefully after floating, and then, in the morning, she sees the blankets on the floor and the glass mantle broken and the chalky powder on her hands, all evidence that the floating hadn’t been a dream.

At this point, Mr. Peebles, a fellow who has an unrequited crush on Alice, finds a way for her to leave the horrible house of animals, girlfriends, and fathers — “nothing can be worse than home” — by sending her to care for his depressed mother out near the ocean. The vet says disgusting, inhumane things to Alice in parting; her mother’s "happy” ghost appears and smiles on the train ride away from London; she meets Mrs. Peebles and falls in love with the enchanted, large house.

On the first night away, in the beautiful house with the large fireplace on an island, Alice lays in her little room:

The bed was most comfortable, and I was just drifting off to sleep when a strange thing happened: I seemed to be floating. I tried to touch the mattress with my hands, but it wasn't there. I was floating above it and the bed clothes were slipping from me...... I did not try to feel it with my hands, because I kept them — I can't think why — neatly folded on my chest. I suddenly realized I was feeling sick. I thought, 'This is bed sickness, not seasickness.'

And then Alice remembers “a similar thing had happened” to after Cuthbert assaulted her. More things happen: Alice learns to ice-skate, discovers the sea, falls in love with a young, privileged townie named Nicholas, learns more about Mrs. Peebles (there was a fire and a suicide attempt, and this explains Mr. Peebles’ concern for his mother).

“At least I wasn’t earthbound….”

Chapter 16 is outrageous and important. While pining for Nicholas, Alice discovers it happens again:

And then in the night it happened again and I was floating, definitely floating. The moonlight was streaming whiteley through the window, and I could see the curtains gently flapping in the night wind. I left my bed, and except for a sheet, the clothes lay scattered on the floor. I gently floated about the room. Sometimes I went very close to the ceiling, but I wouldn't touch it in case it made me fall to the ground. If I came here to an object - a wall, or the tall wardrobe, for instance – some sixth sense seems to steer me away, rather as I've heard it does with bats, and the feeling that this was so gave me confidence.

There is no danger because Alice notices the window is closed, so she can't just float out into the sky. Instead, she bobs about inside the house, where floating is safe, bounded, circumscribed by the house itself.

Finally, she wears herself out floating, and settles back into bed where she sleeps soundly. ,The next morning, she asked Mrs. Peebles if she has ever heard of anyone floating around in their rooms, and Mrs. Peebles brightens up, recalling:

"Yes, levitation I expect you mean. It used to be quite common, I believe, at one time, but I can't remember when. There was a monk I seem to remember hearing about called some name like Joseph of Cupertino, or is that the name of the place in Italy? This man used to behave most strangely, and was not allowed to sing in the choir because he used to rise up and remain suspended in the air and caused quite a sensation and upset the service. This went on for many years, and the poor monk had to remain in his room, where a private chapel was arranged for him. I heard he fasted and practice mortification, but to no avail. Poor man! it was quite an embarrassment for him! My mother used to tell of a man called Home, who was taken up by some society gentleman. He floated in and out of the windows of some big house in London - Ashley House, I think it was. One doesn't hear about that kind of thing now."

It is Mrs. Peebles who first names the floating event for Alice--who provides a word that carries this strangeness. Levitation. When asked if she, herself, ever floated, Mrs. Peebles replies that she would never do a thing like that because: "I'm not peculiar."

And so Alice learns that floating is something “peculiar”, like being left-handed, and therefore something that one must keep to themselves and practice quietly alone in a room rather than “boasting” about in public.

Later on the same day, while sitting among the yew trees in the graveyard, Alice spies Nicholas on a horse with a lovely wealthy girl cantering beside him.... and she wanders out to get a better glimpse, settling on a felled beech tree in a clearing.

As Alice lays down on this beech tree's toppled trunk— calling it her bed — sadness claims her "in waves." She weeps a little, and self-soothes with the idea that maybe the girl is a family friend and Nicholas will introduce them, and she says of this idea:

I almost believed this would happen, but not quite. Then I comforted myself with the knowledge that at least I wasn't earthbound like most people. I lay there on the field tree completely relaxed, and try to will myself to float. I lay there and nothing happened, but I felt drowsy and limp and light. Then I rose in the air, only a few feet. All the noises of the world ceased, and there was a great silence as if from shock at all the laws of Nature being broken. I became afraid, so afraid I became all rigid. Then suddenly I was down on the grass, rather shaken but quite unhurt. I felt a small thrill of triumph. I could float when I wanted to; it wasn't a dream or illness. I really could levitate myself. Walking home in the fading afternoon, I felt a new pride.

And here the chapter ends. Italics mine.

“Much to the alarm of his brethren at the table…”

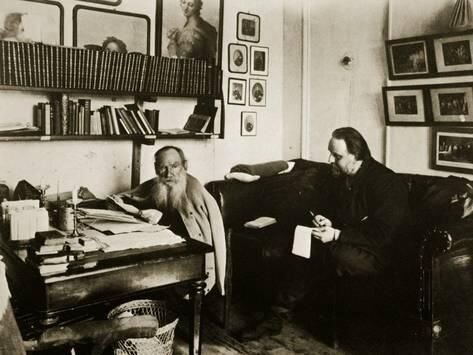

On May 7, 2021, I am reading an essay titled by “Giuseppe” by Eliot Weinberger when I realize Barbara Comyns must have been here (Weinberger says Giuseppe Desa, Comyns says Joseph of Cupertino, but they are two names for the same man).

Also known as “The Flying Friar”, Giuseppe Desa was born to a poor carpenter’s family in a small Italian village in 1603. By age 8, Giuseppe was known to ecstatic visions that left him gaping and staring into space. The story of his life is fascinating—and worth a read—because this wayward soul couldn’t find a home or please anyone or do anything of value until it was discovered that he was peculiar, which is to say, he had inexplicable spiritual gifts or magic powers.

Then Giuseppe Desa became known as the man whose reverence for God was so intense that he lost his toehold on earth. Giuseppe levitated constantly:

On hearing the names of Jesus or Mary, the singing of hymns during the feast of St. Francis, or while praying at Mass, he would go into a dazed state and soar into the air, remaining there until a superior commanded him under obedience to revive. In the refectory, during a meal, Joseph would suddenly rise from the ground with a dish of food in his hands, much to the alarm of the brethren at table. When he was out in the country begging, suddenly he would fly into a tree. Once when some workmen were laboring to plant a huge stone cross in its socket, Joseph rose above them, took up the cross and placed it in the socket for them.

He died in 1663, was canonized in 1781, after which a large marble altar was erected in the Church of St. Francis in Osimoso that St. Joseph’s body might be placed beneath it, where it remains to this day.

“I don’t want to be peculiar….”

Catherine of Siena saw Jesus in the sky when she was seven. A few years later, she ran away from home and sat in a cave where she prayed to God and began levitating.

Hyacinth Cormier of France (1832-1916) levitated while in prayer.

Levitating is part of the ordinary extra-ordinary in hagiographies, and one wonders if Comyns came across such book on the shelves of Kim Philby’s Welsh cottage. That, at least, is my working theory for some of background magic in this book.

Although Comyns is known for her wacky-lovely character names, Cuthbert stood out to me. It’s an usual name—a Celtic name, a (surprise surprise) name common to Celtic hagiographies, likely present in the book of saints Comyns found on Philby’s shelf. The sainted Cuthbert performed some miracles, though its unclear whether he levitated, and he may have envied the levity of a young girl after standing all night in a freezing river as penance, two otters warming and drying his feet (per Eliot Weinberger’s legend).

The contrast between the seriousness of levitation and the frivolous lightness of levity is Comyns’ chord in this novel, and it gets very loud and fractious towards the end. Tragedy forces Alice to return to London, where her father —who hasn’t changed — is drunk and furious and abusive. He hits her and attempts to attack her more, but she floats above him to escape. Like Joseph of Cupertino, she is awake.

The next morning, her father wants to speak to Alice:

“Alice,” he continued, “you behaved very strangely yesterday…er…it was most peculiar.” Peculiar! that word again! “You seemed to leave the ground in the most extraordinary manner and …er…actually appeared to float in the air. I’d be very interested to see you do this again.”

I said, “Oh no, Father, I really don’t want to. People don’t like it, you know. They think it’s peculiar. Oh, please, I don’t want to be peculiar!”

After more haranguing by her father, Alice levitates around the room and descends, feeling depleted, drained, and worried. Remember how Alice learned from Mrs. Peebles that boasting about one’s peculiar parts wasn’t wise?

The word boasting deserves a certain mention here, as the vet’s interest in Alice is directly tied to her peculiar ability to levitate, which is impressive and possibly financially-viable as a public spectacle. He invites his friends over to watch, and they love it; they can’t get enough; someone bring in the parish to witness the mystery-pageant; someone hire a mystery-agent to market this:

Although my levitation had had such a strange effect on these men, they couldn't see enough of it. They kept pestering father for another demonstration, then another, although I heard father say he didn't want me to be worn out already. It was true I was becoming worn out.

Alice calls it my levitation, asserting ownership of it, and the tension arises from what others to wish to make of this peculiarity. When her father plans a public demonstration at Clapham Common that Alice begins to despair:

Rise up before people on the Common and in music-halls and circuses! Please God, don't let that happen to me. Father, don't make me do this thing. I don't want to be peculiar and different. I want to be an ordinary person. I'll marry Harry Peebles and go away and you needn't see me anymore - but don't make me do this terrible thing.

Notice how Comyns switches from Please God to Please Father, mixing up the two a bit, allowing the spectacles of sainthood to share a pew-breath with the spectacles of circus life and capitalism. Earlier, when I said “occult” wasn’t quite the right word for the bang-up sacred-profane stew that Comyns is serving in this novel, this is what I meant. The patriarch is the head of the house, the king of the church, the master of ceremonies, the deliverer of death, and the daughter — at best— may get to play steeple to his te deum.

Like most decent female characters in this book, Alice Rowlands dies in what could be considered a tragic accident or else the plan of a powerful man-god playing with chess pieces to better his game. I love how it ends in the tawdriest inquest. I love how an inquest may be the carnival-modern version of a hagiography. I love how the tragic language of recent young moms murdered by spouses in the latest Birmingham news story always creates a portrait which verges on sainthood, as if the only worthwhile grief is that shed for a saint or a martyr. I love how Alice’s dread turns out to be correct. I love how Comyns does nothing to make this ending cozy or instructive. There’s nothing to learn, really. One can’t levitate one’s way out of the mess, the vet, the system, the obit.

Speaking of making one’s peculiar parts public, the writer’s role (or unique privilege) is to reveal their peculiars on the page. We all hope that the inquest is distant and the audience enjoys the show we make of our minds for their entertainment and pleasure.

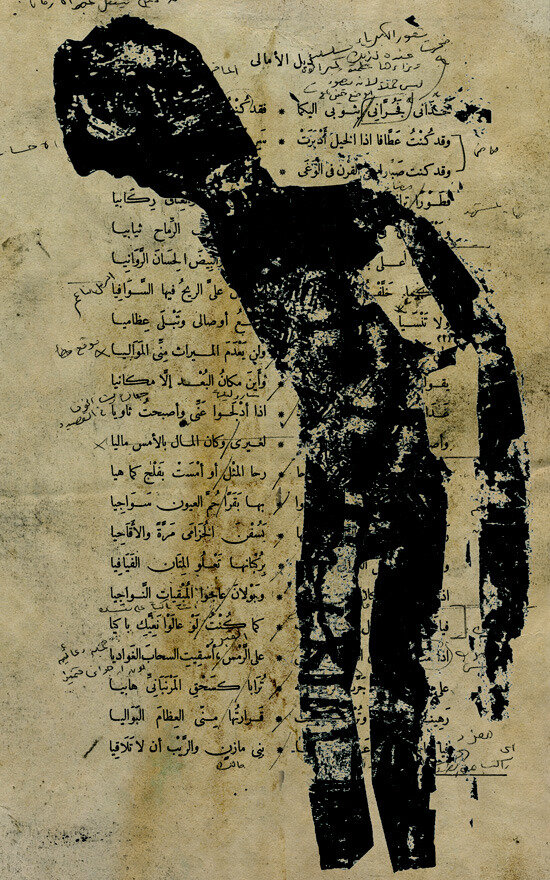

![Cubas atop the donkey—though the muleteer is missing. From Mariana Rio’s illustrations for Memorias Póstumas de Brás Cubas published by Editorial Sexto Piso. [Source]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5aea0d8696e76f6ac6f09e3c/1616020838918-CFGHQWYZQ4CI1RCFR42W/Screen+Shot+2021-03-17+at+5.39.48+PM.png)