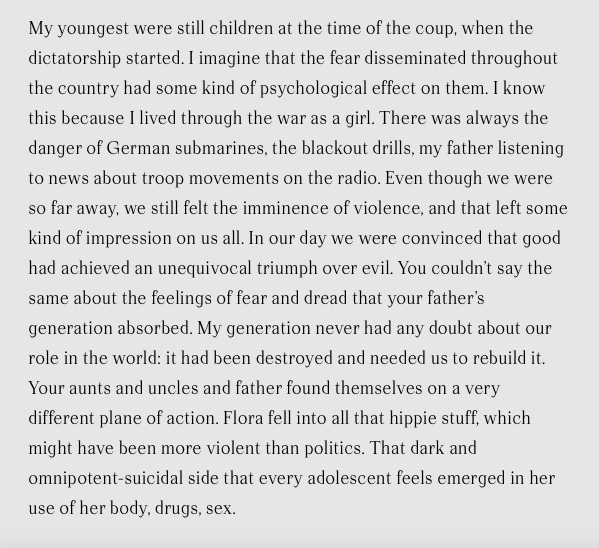

Our ability to attend to what we love, to name what we love, to honor what we love is also our ability to preserve what we love. There are many things that probably do that, but one of the things that we know does it, as well as anything, is poetry. Poetry is the intense and devoted study of everything—of plants, of each other—in a way that is not utilitarian, but is actually about the heart. It is among the things that I think gives us our best chance. That close looking, that wonder, that devotion, that care, and that love. Studying love is also one of our chances.

Ross Gay

Satisfaction is overrated anyway, I think, and it's an American idea that one ought to feel full in order to be satisfied..."I think it's alright to be always a little hungry....

Sarah Manguso in an interview

1. The tension in romantic love is generative.

Love isn't an emotion or sentiment. Love is more like a way of seeing, a gaze geared towards the desire to see better. To see closer. To see again. To stay riveted. Love enables us to "see" things in vulnerable, rapturous ways. The particular look of love assumes an agreement to see in good faith, to see the utmost in a person, place, or thing. There is a form of fidelity in this, a faithfulness. We are bound by that seeing--and love lasts as long as we indulge it, and allow flux and change to absorb what happens within that gaze. Whether the beloved is a human, a football team, or a pet rodent.

Another way to think of love is as an apprenticeship to longing, a relationship between the world and what one wants from it.

I can't recall a time before I knew physical touch was both appetite and hunger with no good breath between. And no finale--only the continuance of into-ness. I want to talk about how we see through the love lens, and how we challenge ourselves to write it.

In The Book of Delights, Ross Gay uses a form of micro-CNF which he calls "essayettes" to touch the things which delight him daily. He describes that moment when "when crave became an inarticulate state of being" for which a song can be "red carpet," an unfurling-of.

I love when Gay acknowledges that "hunger, itself, is sometimes a kind of pleasure." Because hunger is my favorite part.

When I say hunger—I mean wanting something in a way that holds your imagination and turns road signs into moats between what you want and what you can survive.

When I say knowledge, I mean memory gives life to chairs while history makes sense of stones.

When I say stricken by hunger, I turn words into bread crumbs and lose the way. I forget what to fear and what to preserve. There is something both animal and not-animal in it. Like the deer we hit on a back road in rural Georgia, the soft smudge of her surprised-open eyes, the slowness with which life left them, blank . . . — And the old adage that entered my mind, the warning that any animal you kill will howl on your grave for eternity, robbing your bones of peace and rest. Unless the loved ones know your hunger, unless they've inherited it, in which case the spirit of the animal you killed will help your beloveds find their way back to you in the dark.

2. The book of love is long and boring, no one can lift the damn thing. [The Magnetic Fields]

To be in love is to stand inside a fire, to be lit by a same match and yet burn differently, to be "both crazy in the same way," as Rachel Carson wrote in a letter to her married female lover.

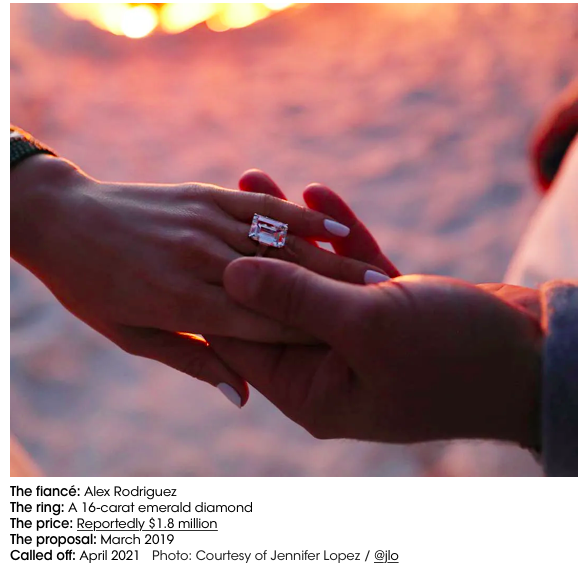

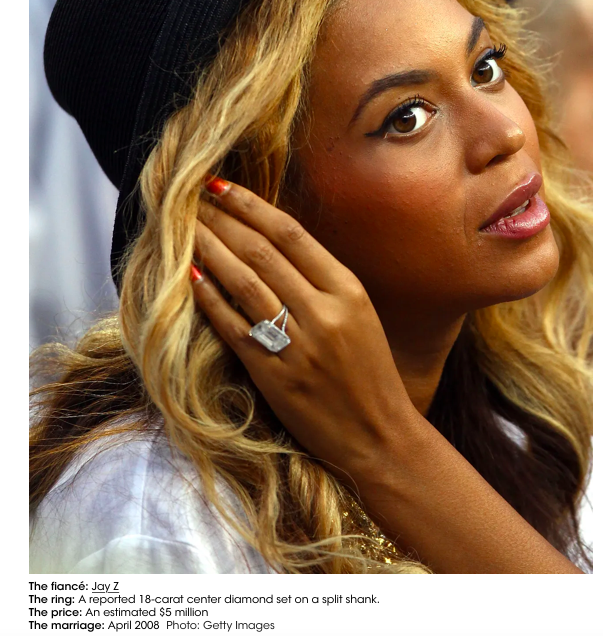

I pick which sign of him to display on my public body, which symbol to pledge, which emblem to connect person and troth.

I keep my hair the loud wreck his hands made of it when I walk into the office, the matted-hay bun, lips pink with the tingle of bearded kisses. My body is a poem under pressure, a tree whose trunk is marked by the most powerful frictions.

If all the air is sucked from a chamber, a feather and a brick will fall at identical speed. It is the presence of air that slows the feather's fall. It is the space around us (and how our bodies occupy space) that sets those conditions. It is the white space in which love takes place.

There is that moment when one is leaving, and the room settles around absence. And some of the power in the story you tell about love derives from not saying everything. Just like some of the power in love as longing derives from not knowing or having everything.

Love is a hard gaze to sustain. The tension between wanting to know and familiarity is always present in a love poem. Just as the fear of being misunderstood looms large in love's languages, both verbal and physical, the long chain of innuendo.

See "Connubial" by Stephen Dunn for the simplest exposition of this tension.

See Thom Gunn's "In Trust" for the tension between long-distance love and trust, which is a cognitive state that relies heavily on familiarity and the belief that one can know another person's actions or emotional states in a reliable (and therefore "safe") way.

And yet distance keeps fantasy intact. It makes every encounter feel like a fresh choice rather than a settlement. Even in passion, we need to offer the sense of choice to weigh against the compulsion to touch and feel.

Roland Barthes noted how the lover's "double discourse" divides the gesture, or expression of love, from the sentiment, or embodied feeling of it. The "double vision" renders the other sometimes object, sometimes subject. The mask grows into the face. To quote Roland Barthes quoting Descartes:

"Loratus prodes: I advance pointing to my mask: I set a mask upon my passion, but with a discreet (and wily) finger I designate this mask. Every passion, ultimately, has its spectator..."

Every love wants to be seen, spoken, savored. Even if the object of love doesn't care, the love itself wants declaration.

3. I mean: I love the way he sees me.

I love feeling his eyes on me as I eat. There is something intimate about witnessing a human's attempt to sate hunger—something splendid about fingers rolling back the peel of an orange. The incompleteness is acknowledged, a person draws closer to a true story, or the one that will go on without us, the story of what we lacked.

I don't know which urge is stronger--to consume or be consumed.

The hunger is my favorite part because it's the magic blank, the cloud of anticipation, the simultaneous sense of floating and yet existing as palpability, the state of feeling as a modality, to feel and be felt.

Is there a restless profanity in looking?

Isn't the looking, itself, as reckless as the eyes of a poem in its desire to covet?

"Did you ever feel colored-in when a boy found you with his mouth? What is the body, at best, is only a longing for a body? The blood racing to the heart only to be sent back, filling the routes, the once empty channels, the miles it takes us toward each other. Why did I feel more myself while reaching for him, my hand midair, than I did having touched him?"

Ocean Vuong, On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous

This is how Ocean Vuoug describes his first lover in this stunning book. Vuong is drawn to his own edges by the stark revelation of his lover's. What he wanted was "not merely the body, desirable as it was, but its will to grow into the very world that rejects its hunger."

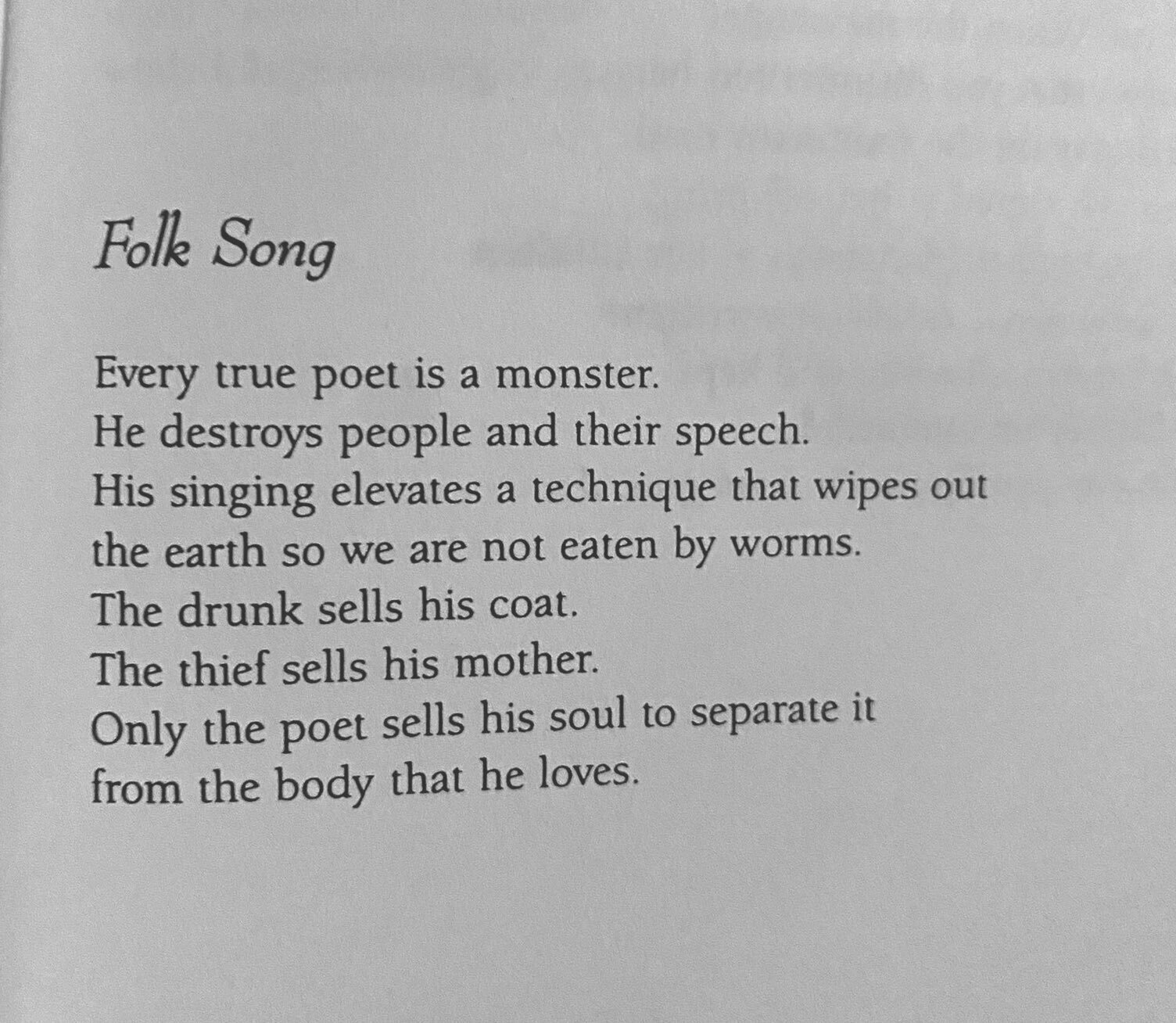

Desire transforms us. Desire demands both tear and transformation. Desire is where the lover originates, "a place on fire, a place he could never return to." Every time I sit down with a poem in my mouth, it is the first lover--it demands the same thrall and humility, the same abandon, the same obsession, the same pyre with the promise of ash.

4. I mean: I love looking back.

I am writing a poem to my mother who is sitting in a patch of clover sucking on a blade of grass. And laughing. Yes, she is laughing openly, shamelessly, closing her eyes to let the sun lick her face. I understand the sun can be kitten and Mom can be living for this time. On the page.

The hunger to write is bound by the addiction to remembering. Or allowing this memory to live, to grow flesh and steal a life of its own.

Here, in this Lipton meadow, Mom is whole. The parts of me that only exist in her presence open their eyes. When I write, I have a safe home, a childhood, a feather pillow, a secret language in which I am known.

"You fill the world. I can only escape you in you," Marguerite Yourcenar wrote of a man.

Maybe life is a paradox about hunger and poetry. Like the end of Carl Phillips' poem, "Civilization":

How they made

out of shamelessness something

beautiful, for as long as they could.

Read the whole poem. Notice how Carl Phillips begins the poem with this abstraction, the "ongoingness". Note how Phillips rubs this word against others--including "always"--as the poem progresses. And the longing to know love, to be known in love, to be reconfigured in the words "I love you"...

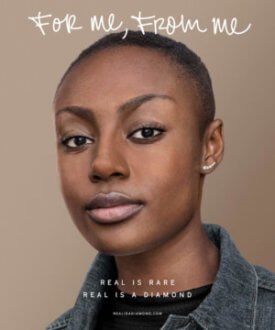

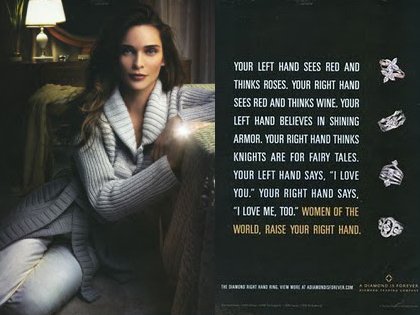

When I say being known, I mean writing reveals us. Writing exposes what we treasure, what we fear losing. The market creates artificial hungers for orange corn puffs, and we, as human poets, are tempted to respond with our personal descriptive engagement of consumer appetite. We find a way to belong by wanting to consume the same things as our friends and neighbors. I wonder if this is an occupational hazard.

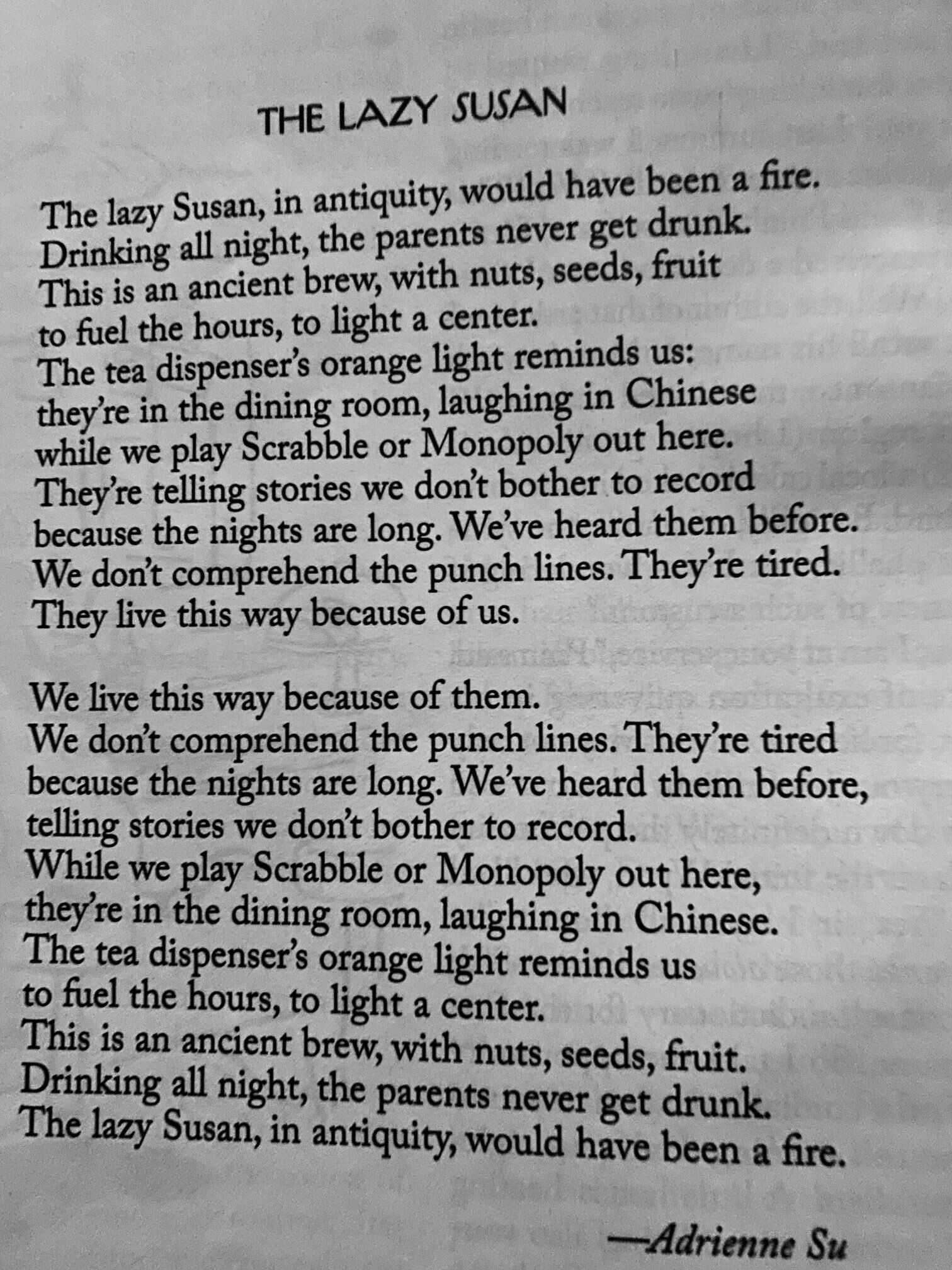

5. Repetition and fidelity

M. and I wind up in Paris at Pere Lachaise cemetery. Two steps from the bones of Oscar Wilde, M. snaps enough photographs for a cotillion. I pack cotillion near other Alabama words that dress up in French.

Construction crews pave walkways with noisy machines. I prefer silence in a graveyard. The buzzing sounds are bothersome. I can’t remember what Oscar Wilde wrote apart from the quote about temptation. Given automated buzz. A buzz is the point where one decides whether to take the next step towards intoxication.

I say sure. M. is my high school sweetheart. The edge of a buzz I will probably marry. A high school sweetheart is not sweet like marshmallow Peeps or caramel. A sweetheart can be scant on the sweet and high on sticky. A girl can snap photos but not her fingers if feelings get sticky enough. When I sit down to write this, the word sticky appears like a Greek chorus.

Repetition of words or phrases can hold a poem or short prose piece together, like the thin skein of lime green in a curtain coordinates with the couch pillows. When writing love, repetition creates an illusion of fidelity by invoking memory--the narrator is faithful to the memory that the words repeat and reenact.

I'm obsessed with the way Eileen Myles uses repetition in "Peanut Butter". Notice how it begins with abstract "I" statements:

I am always hungry

& wanting to have

sex. This is a fact.

Myles spends the rest of the poem making the "I" and "you" palpable with imagery. And then they turn and ends the poem with three short, stabbing "I" statements. That "re-turn" is so powerful--as are the enjambments of words with "re" prefixes.

When you sit to write love or hunger, jot down any words that come back as pivotal or emerge as refrains in your thoughts on love, both general and specific. Each of these words is a bead worth setting aside for a bracelet you might make later.

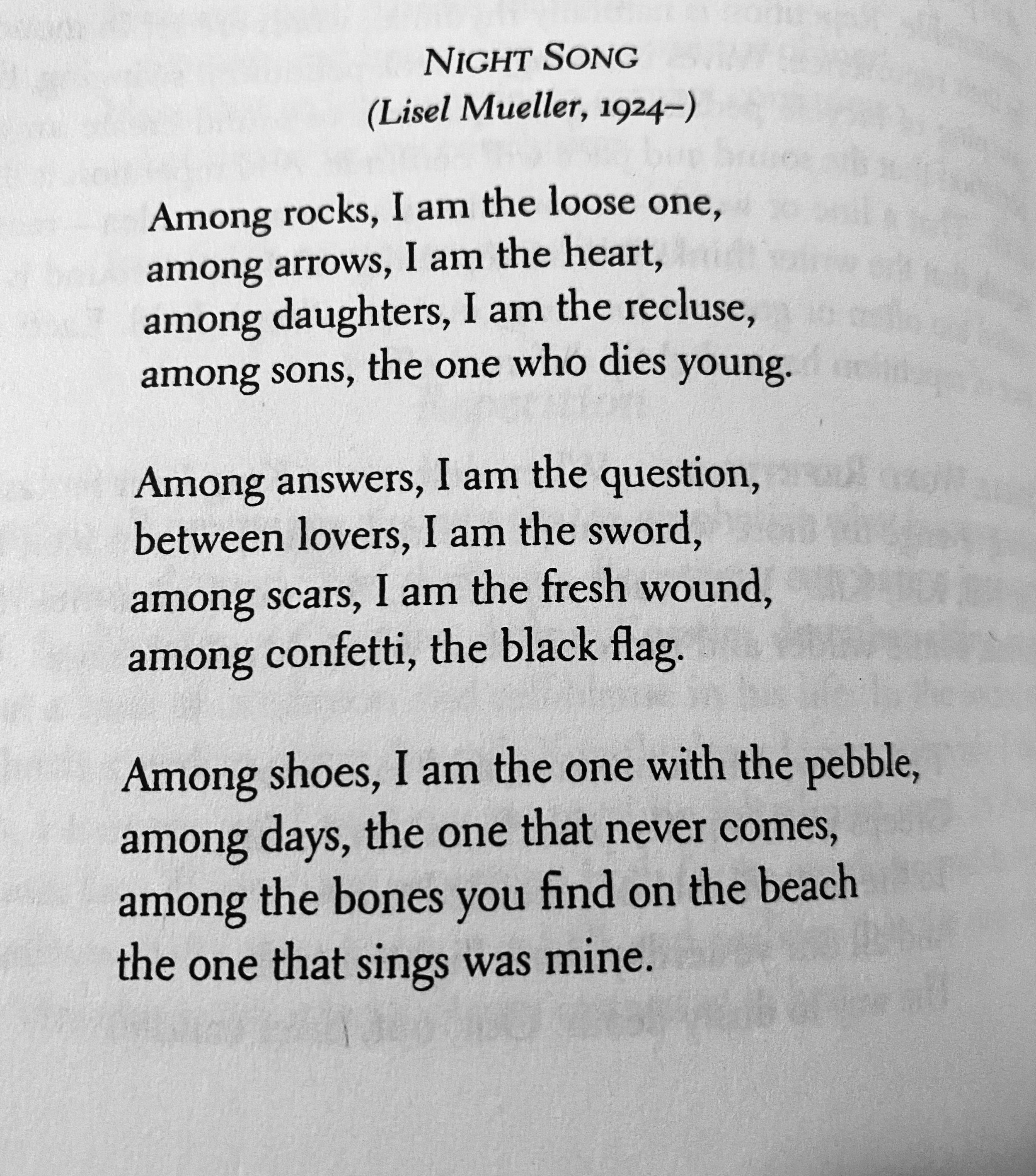

What does this have to do with aubades as a poetic mode? Not much—except the soil. I’m teaching a workshop on aubades this weekend and getting ready to play with this beloved form in a very small group, and thinking aloud as I review notes.

I think Jake Adam York described the aubade perfectly:

"The aubade is a poem of the morning, of sun-up—though it’s also a poem of endings, traditionally presenting a farewell, from one lover to another, as one departs before the light catches them together. Since aubades both open and close, these poems seem capable of great depth or complexity of emotion—and they offer many opportunities for innovation."

Maybe I’ll add more later . . .

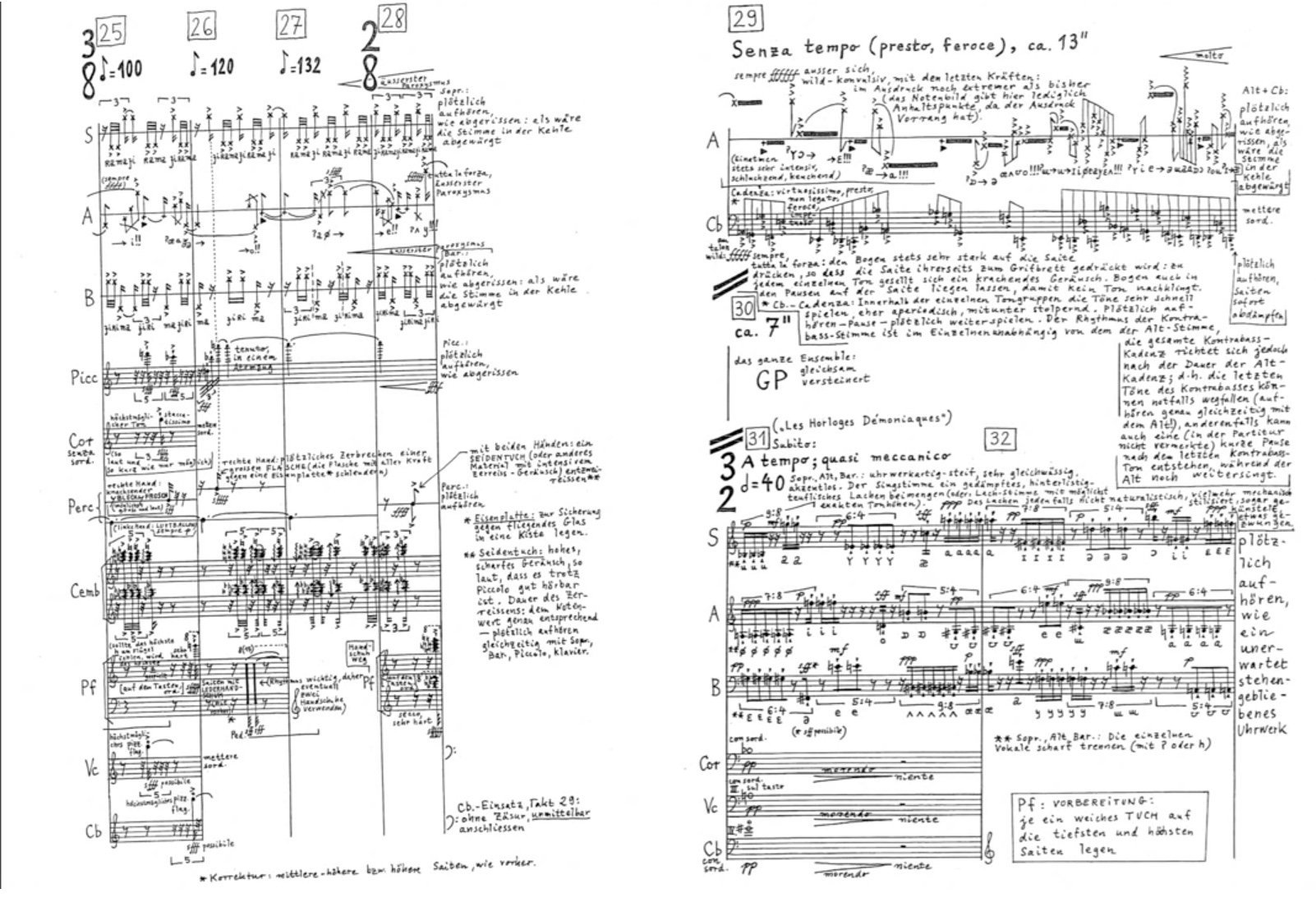

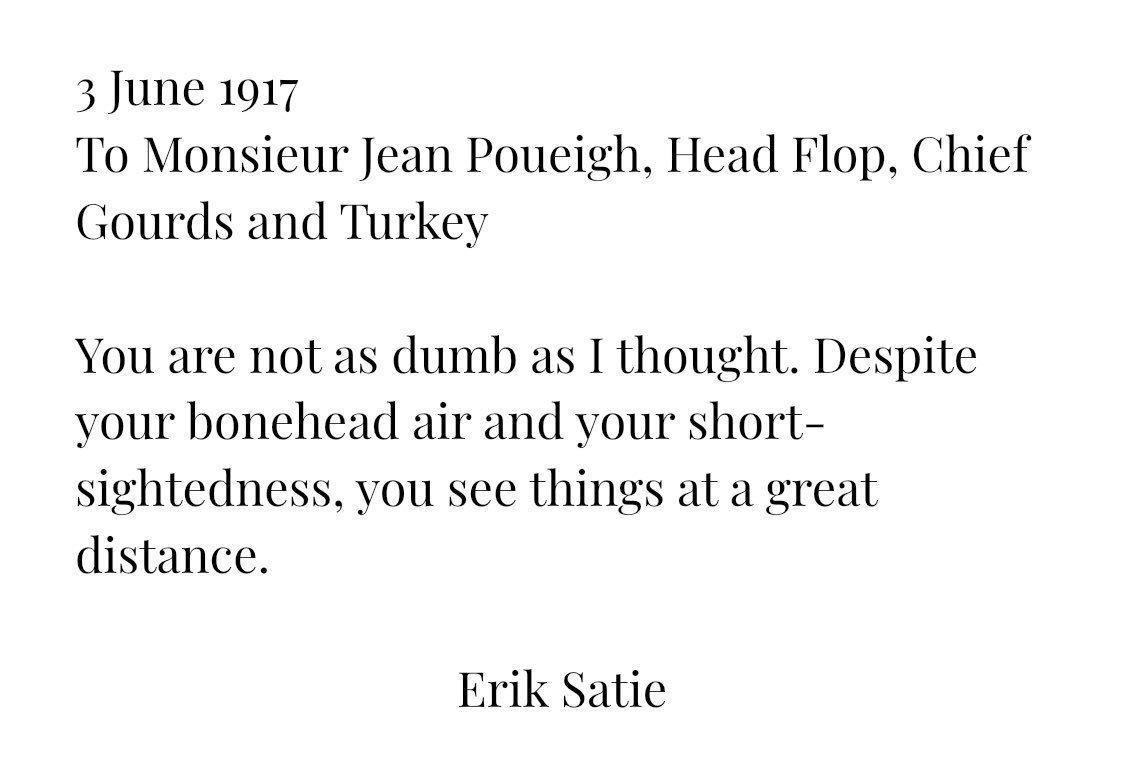

Aubade-making Playlist

And here’s a playlist for aubade-making later, various leave-takings to use when writing or reimagining the form an aubade can take. It helps me to listen to music, to hear songs that offer different lyrical images, or invoke certain rhythms. Sometimes the aubade begins before the sun rises, and I think that’s the electrified version, the walking a street at night doused in neon. There are so many ways to leave, and to be leaving. .