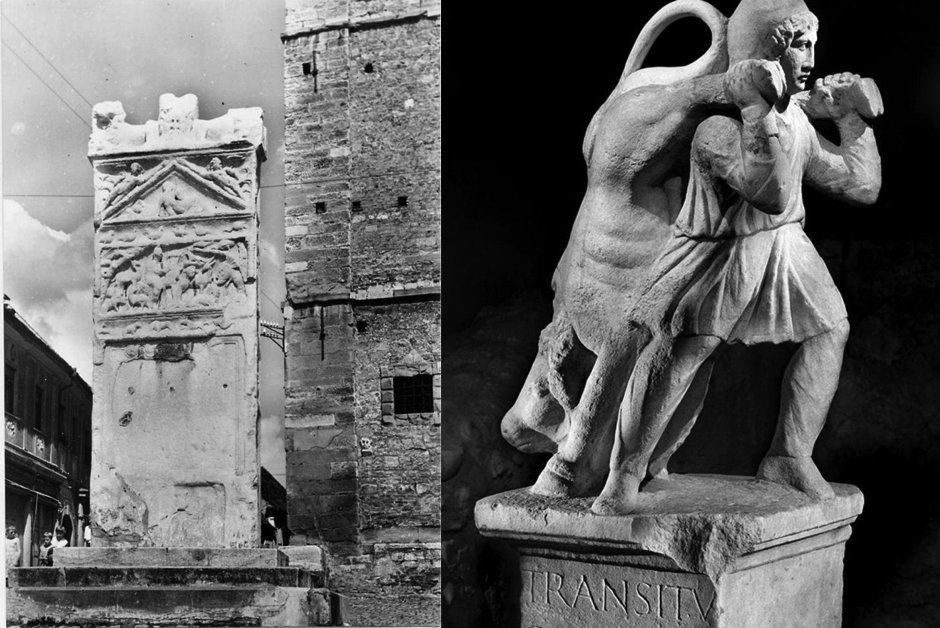

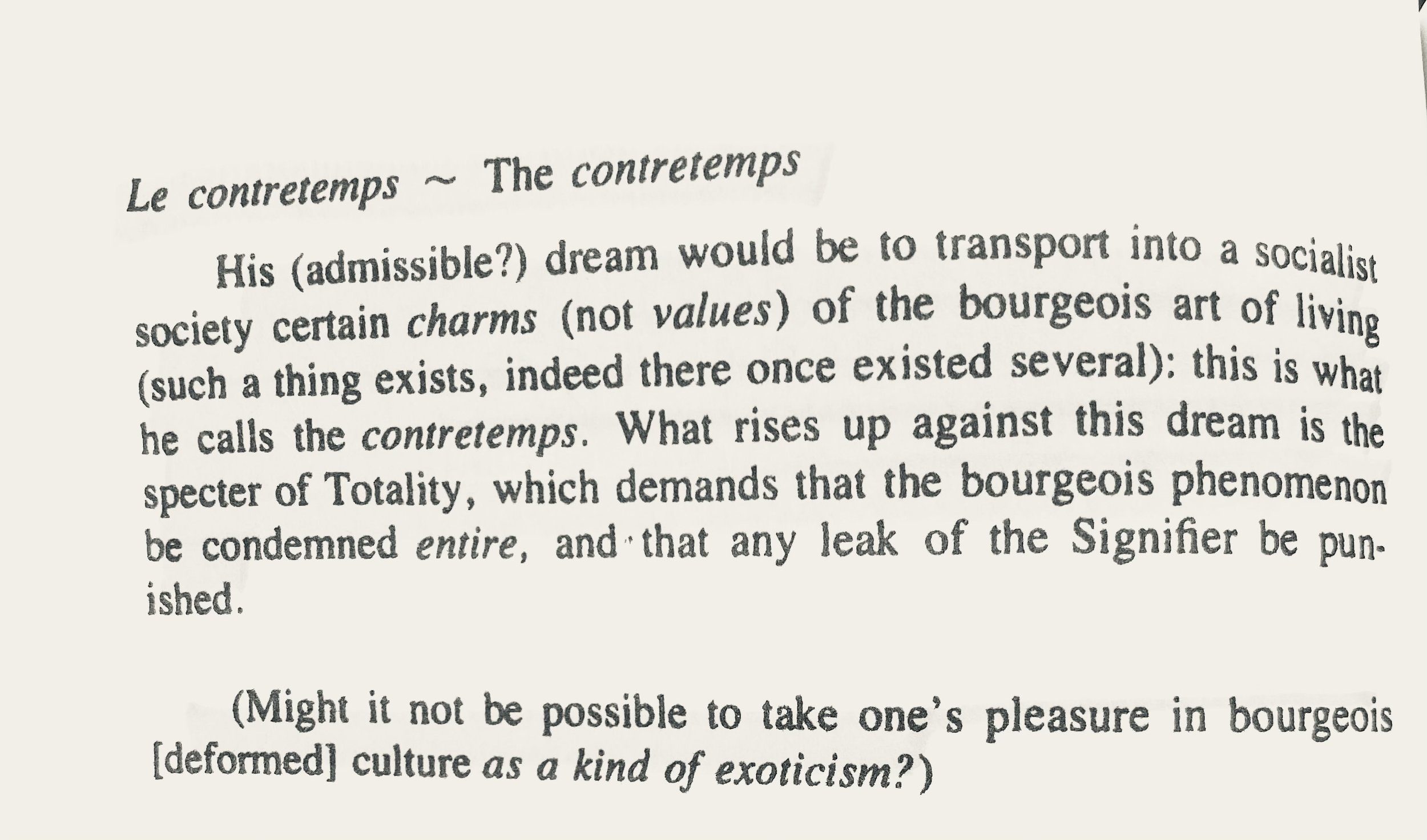

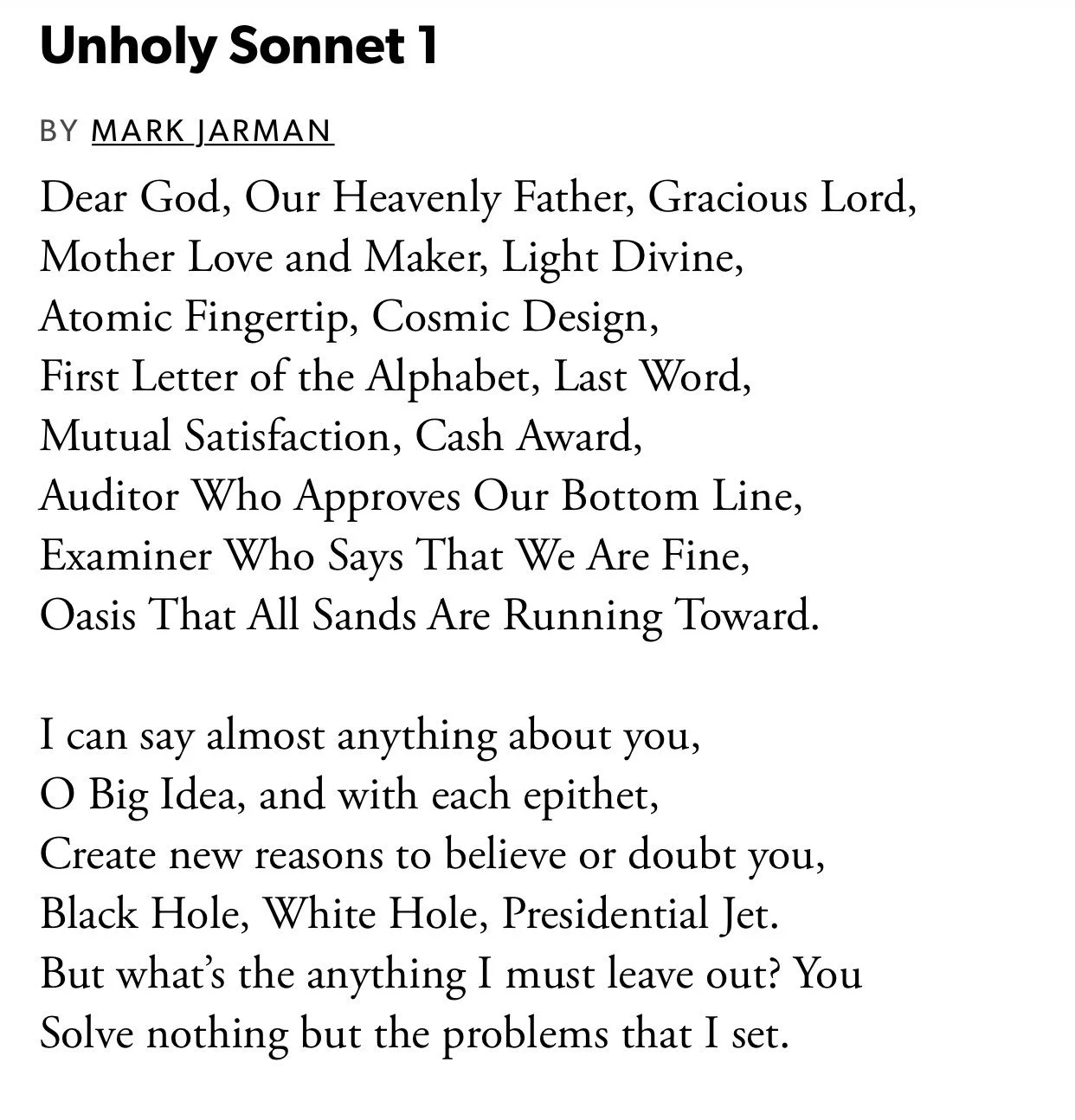

The language of ruins — the presence of ruinscapes — is central to my current manuscripts. But so much of what compels my thinking will be left out of the poems, the essays, the novel . . .

So I leave these crumbs for myself, should I wish to retrace my journey in a space less chaotic than notebooks: the relationship between the icon and the monument, between love and eros, between seeing and beholding, between imagining and destroying.

In an essay, “Summer of the Statue Storm,” A E Stallings looked at Georgia’s famous Stone Mountain, a monument to the Confederacy, while reading ruin-guru Susan Stewart. In Stallings’ words, and quotations:

As Stewart concludes in her last chapter, “Resisting Ruin: The Decay of Monuments and the Promises of Language,” “Monuments are among the most controversial of built forms, and their controversy always lies in their inadequacy and in the inevitability of their failure.” A monument is a future ruin.

Reading Stallings brings back the goosebumps of reading Stewart and discovering connections between conventions, language, and social valorizations:

The fragment is cousin to the ruin, as the unfinished building reflects the collapsed one. “Companion to the ruin, the unfinished is not the sign of a damaged form but the sign of damaged intention.” The Tower of Babel is the ur-unfinished building—or the unfinished building of Ur, perhaps. Its most famous depiction is the much-reproduced painting by Pieter Brueghel the Elder (or paintings, to be precise, as two versions are in existence, slightly varied, like an early spot-the-difference game), itself based on a ruin: he pictures the mythological ziggurat after the breakdown in human communication as a lurching wedding-cake pile-up of layers of colonnades based on the Roman Coliseum.

Modernism thus is a kind of culmination of the ruins lesson, with its fetishizing of fragment, its palimpsests, its Babel of language and voices, its concern with the “age value” of ancient quotation, and its fascination with physical ruin.

“A quotation is also a way of engaging a ruin, or fragmenting the monument known as a text,” I think to myself, while reading Stallings’ beautiful essay.

“Perhaps saliency, itself, is a form of intertextual relationship,” I wonder, while recognizing words and phrases that I kept in my notebook when immersed in Stewart.

Surely Stewart must have mentioned damnatio memoriae? What other coincidence could cause it to pop up in both Stallings’ thinking and mine?

To quote Stallings:

Scholars have been busy telling us that iconoclasm is nothing new, reminding us of the Roman practice—cancel culture, if you will—of “damnatio memoriae,” or condemning the memory, when the Senate would try to erase every image and inscription relating to an individual, and even their families. Caligula and Nero are among Roman emperors treated thus; they have hardly been erased from history.

Also on my turntable as I finish quibbling with the poetry manuscript, the ruins of angelology, the hagiographies of motherhood, “In Labyrinths” by Martin Pops (also known as Marty Pops), “Resisting Left Melancholy” by Wendy Brown, and, of course, the echoes inside Paul de Man’s “Autobiography as De-facement”.

Music: “Into the Light” by J. Views ft. Wild Club

*

Is there something like a ruin in disappearing? Or does the ruin rely completely on a physical chipping-away in order?

I don’t know.

"I am indifferent about being missed," writes Hanif Abdurraqib, thus opening his essay, "The Art of Disappearance." Being rooted in his own contingency is perilous:

“To drill down on the definition of “being alive,” I have always come to a core definition that I can understand and make peace with: being someone who participates in the ever-shifting world. But I have no control over the world, and I don’t mean only the world in the sense of a blue rock twirling along endless dark. I also mean the smaller worlds.”

The smaller worlds include the immediate challenges of relationships, the persistence of his depression, the self's relation to self. Relationships expect things–they presume presence and bloom from anticipation. The more presence asks us to perform a certain openness, or emotional lability, the more it costs.

There are kinds of leaving, disappearing, and changing one's mind in a way that removes you faster from the presence and awareness of others.

Sometimes, on the playground, I lied when the other mothers asked what my husband did for a living.

I pushed my son back-and-forth on the toddler swing and said: he is an engineer. Or a teacher.

Once I said my husband managed the gardens of the elderly and disabled, a sort of janitor for beautiful green spaces which felt like homes to their owners, but which their owners could no longer maintain.

My husband was out there, somewhere, in those moments when I was asked to imagine him.

But I was a single mother. There was no husband or partner. No ex or divorce.

It is easier to disappear in the expectations others have of you than to exist as a perturbation of the normal. Ruinscapes aren’t merely perturbations of the normal—-they are repudiations of time which articulate alternate temporalities. It is the precise nature of the ruining destruction which most intrigues me.