I am dumping this essay here from my own notes, in case anyone is interested in Irish literary critic Denis Donoghue’s reading—which has, I think, some very compelling, or well-complicating, parts. Like many Eliot acolytes, Donoghue misses some things and avoids reckoning with others, but his frolic with de Certeau’s tactics and ruses feels keyed to this cold winter’s night.

Near the end of Plato's Phaedrus Socrates raises the question of writing as distinct from speaking, and he quotes the Egyptian god Thamus as saying that the invention of script damages the power of memory in those who write. Socrates goes on to attack script on the grounds that, like a painting, it has nothing to say for itself, it can't take part in a dialogue: a crucial disability. Writing may be useful to remind oneself of something, he concedes, but it shouldn't be taken seriously otherwise: the only true writing is what is written in one's soul.

But the Phaedrus had little or no impact. Brian Stock has noted that "most of Plato's writings disappeared at the end of antiquity; they were not known again in the West until the Renaissance." During those centuries, script established itself as a worthy sign of speech and was used accordingly. Therefore the reading of a manuscript was for long a slow and noisy affair as the reader tried to convert written words into sounds.

The skill of silent reading was a late achievement. I speculate that one of the reasons why, in reading Yeats's poem, I try to divine the speaker's voice is that for many centuries reading entailed the conversion of script to audible sounds; the reader's voice tried to be in unison with the original voice designated, however inadequately, by marks on clay, bone, parchment, vellum, or cloth.

Historians of orality are in apparent agreement that orality is the sign of lives social and convivial rather than individual. In an oral society people are members of a "collective assemblage" - to use a phrase explicated by Deleuze and Guattari in A Thousand Plateaus—before they are isolated individuals (if they are ever such). The dialect of the tribe is not only the context in which people engage in social life: it provides the means by which an individual may speak. It follows that reality in an oral society is construed as mainly temporal: hence its appropriate paradigm is the in-and-out of one's breathing. Temporal, dependent on memory: reality is interpreted as historical, it assumes a narrative form of understanding, as in the epic. Memory is the enabling capacity, repetition is its convention, formulaic narration a practice of its genre. The speech of the place is not soliloquy but conversation.

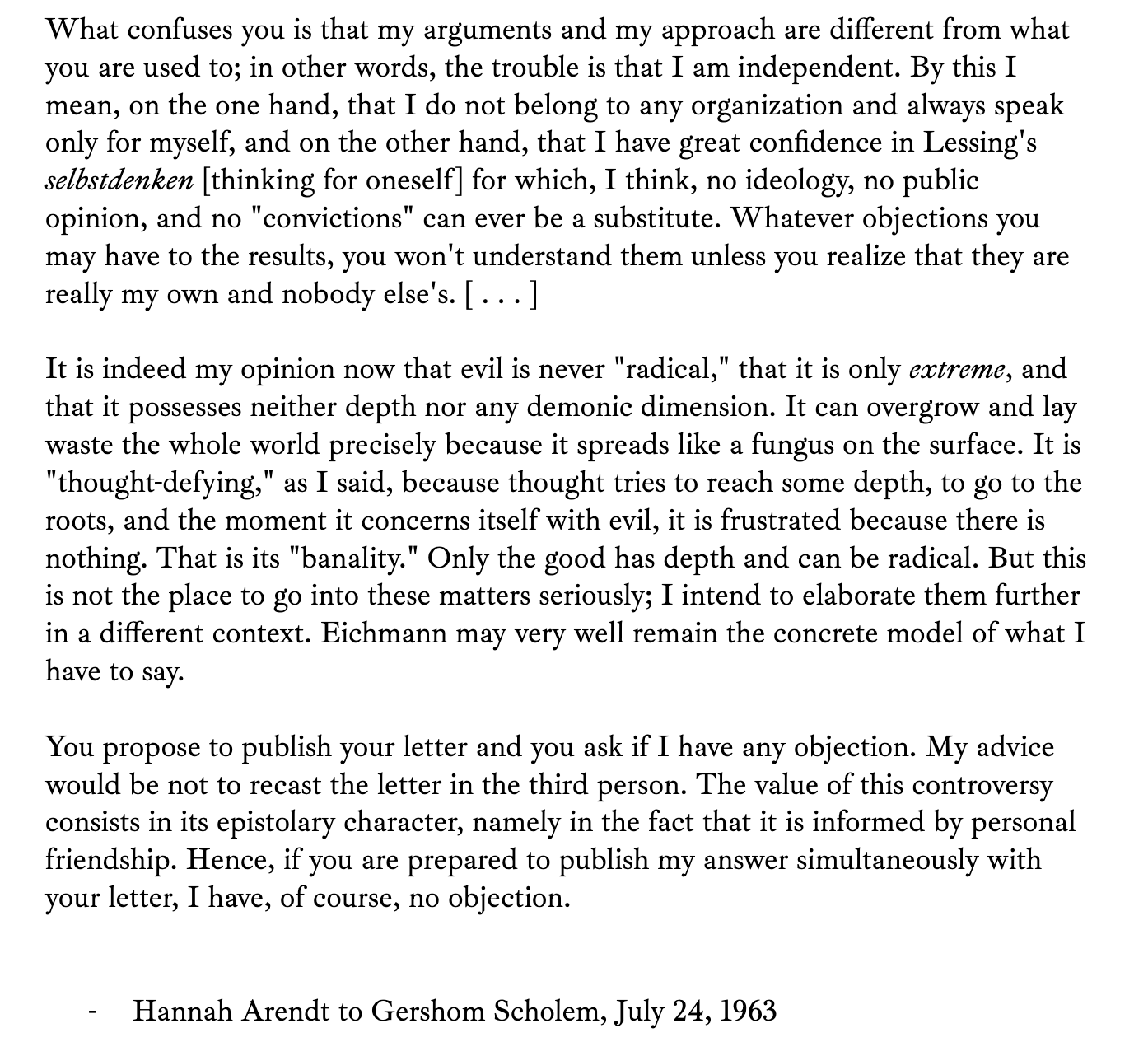

It follows, too, that politics has been directly associated with conversation and oratory. Hannah Arendt, thinking of the involvement of scientists in the development and use of the atomic bomb, said that the "reason why it may be wise to distrust the political judgment of scientists qua scientists is not primarily their lack of 'character” —that they did not refuse to develop atomic weapons—or their naivete—that they did not understand that once these weapons were developed they would be the last to be consulted about their use—but precisely the fact that they move in a world where speech has lost its power."

These conditions of orality were radically, though only gradually, changed by literacy and especially by the development of alphabetic movable type in Europe in the middle of the fifteenth century.

Writing and reading are for the most part solitary activities conducted in a world of mainly spatial relations.

Historians of orality and literacy —I'm thinking mainly of Albert Lord, Milman Parry, Marshall McLuhan, Eric Havelock, Elizabeth Eisenstein, Walter Ong, Jack Goody, Michel de Certeau, and of other scholars who are building on their work—generally agree that after the achievement of silent reading, the act of seeing words on a page entered into the constitution of knowledge. [….] Knowledge entails what Havelock calls the "recognition of the known as objects."

Orality suffered a severe blow when people started believing that our primary relation to the world is one of knowing, and that knowledge should be substituted for other ways of being active in the world. It follows from that change of mind that reality was assumed to be fully described by knowledge, the distinction between subject and object was used as the chief device of knowing, and knowledge was supposed to be fully achieved by science. We reach the stage, which Brian Stock has described in relation to the early Middle Ages, in which "objectivity was identified with a text." Those beliefs were consequences of writing. Further consequences included the move from custom and tradition to law, from an oral promise to a written contract, and the designation of a noble family by genealogy rather than by the scale of its local affiliations. Reality was now deemed to be separate from the mind that engaged it: its qualities were supposedly those of script-relative stability, objectivity, an enduring existence out there, waiting to be observed and interpreted. Observation was the official form of attention. Method became the habit of observation amounting to a conviction. God was believed to have given mankind two books—the Bible and the book of Nature—gifts that could be appreciated only by people who lived in a world of readable script and the opposition between them appears more severe than it is.

[....] Many societies have practiced orality and literacy together. Orality is never merely displaced by writing; if in a particular society it is, it is changed by the pathos of that displacement.

De Certeau has pointed out that "Orality becomes something else from the moment when writing is no longer a symbol but rather . .. the instrument of a production of history in the hands of a particular social category." He mentions the confidence that intellectuals of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution felt about the power of the printed word: "writing was to refashion society in the same way that it had indicated the power that the enlightened bourgeois was ascribing to itself." To the degree that writing becomes the communication of works through which a society constructs its progress, orality is changed, displaced, as if excluded from the official record. "It is isolated, according to de Certeau, "lost, and found again in a 'voice which is that of nature, of the woman, of childhood, of the people." It becomes pronunciation, apart from the technical logic of print and its ideology. It becomes music, song, opera, a "space where the organizing power of reason is effaced" and the singing voice stretches or leaps toward a sublime beyond reason. What orality speaks of is whatever reason designates as superstition, passion, stirrings of an indeterminate self, the sublime: "it is voice separated from contents. "

But the transition from one technology of expression to another is never abrupt. De Certeau has noted that "epistemological configurations are never replaced by the appearance of new orders; they compose strata that form the particular values of print imposed themselves and established a new decorum.

This entailed a revised sermo humilis, a plain style supposedly correlated to the quiet act of observation and the morality of speaking truths deemed most convincing when they were plainly delivered. Stability was enforced by grammars and dictionaries. Meaning was declared to issue, as in the rhetoric of the Royal Society, from the correspondence of word to thing rather than from an intentional relation between words and their speaker. Indeed, the ease with which words in a culture of print could be separated from their speaker and from a natural world accounts for the development of new forms of writing and new styles, especially in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

These arose from the first consequence of writing, that words can reach people to whom they are not directly addressed. In conversation, what I say to you and you to me and what we make of the exchanged words are nearly simultaneous, active in the shared context. But if I write the same words, they may be read by people I have never met. What I say and the decorum of my speech are governed by the local situation as I construe it. But what I write must observe a different decorum, since I can't know who may read my words.

My sense of readership is not the same as my sense of a particular audience.

These equivocal conditions, especially in the seventeenth and eighteenth century purveyors of the Marprelate Tracts, and to those high-toned writers who wanted to avoid the stigma of being professional authors, scribblers, ink-stained and low class. The separation of print from an identifiable voice was a necessary device, too, for writers who had to disguise themselves at a time of Licensing Acts and the paper wars between political disputants, some of them Whig and Tory. The printing press also made it possible, for writers so dis-posed, to thwart the common desire to hear particular voices even through the mediation of print. Think of Jonathan Swift's breakages in the text of A Tale of a Tub, Laurence Sterne's blank page and the squiggle of print in Tristram Shandy, or—moving forward a century—think of Mallarmé's refusal of acoustic eloquence in Un Coup de Dés. In our own time Concrete Poetry deploys words as objects from which every trace of a singular authoritative voice has been removed. Print also makes possible omniscient narration, the indirect free style, various forms of impersonation, and styles of willed neutrality, as if the story were being told, but told by no one. It may also incite writers to devise rhetorical stratagems precisely to recover the flourishes of speech and gesture that a culture of print supposedly suppresses. Thomas Sheridan's Lectures on Elocution (1762) and Lectures on the Art of Reading (1775) were evidently designed for that purpose. Yeats's "A Deep-Sworn Vow" was composed to intuit a voice. An entity that is still predicated on the oral persuasion of person to person, preaches to congregation.

But what about the electronic media, computers and information technology? If the technology of print enforced its values but still allowed voices to be heard, surely the electronic media will be even more hospitable to voices? Isn't TV almost entirely voice and body? Aren't e-mail and the internet a constant exchange of implied voices? Surely orality must come into its own again?

The prudent answer is: not necessarily. What orality had to fear from script and print was the fate of being silenced, its values displaced. What it has to fear from the electronic media is the abjection of being teased and mocked. Walter Ong is helpful on this question. He calls the present age, so far as it is governed bv electronic developments, an age of "secondary orality. He means that the conditions provided by electronic technology are similar to those of primary orality- the orality of an oral society - in superficial respects, but different in profound respects. They are similar, in that the events we witness are oral and are suffused by oral elucidation; but they are different in that TV merely mimes orality, displays simulations of spontaneity, and pretends to show social formations as open and permeable. According to the pattern of consequence he has already indicated, Ong expects to see the institutions of this secondary orality causing the production, at least in the short term, of more books than ever; but these books will more and more clearly submit to the values of the new media. I suppose he means that most of the books on the bestseller list will be parasitic upon TV programs. That is already and dismally the case. Perhaps Ong means that increasingly writers will write as if for TV, or to reach a readership of people accustomed to the situations and the dialogue we see and hear on TV. And presumably readers will gradually come to insist on the styles and the conventions they see on TV.

This seems probable to me. Every new technique, from the printing press to photography, film, audiotape, video, and computer games, has had some impact on the common understanding of the world. Those of us who grew up into a literature still open to voices are likely to be bewildered, perhaps dismayed, by further developments. But all is not lost. I have been much encouraged by one of the arguments in de Certeau's The Practice of Everyday Life. He acknowledges that at any given moment a particular system of power is in place, a syntax of social and political practice. But he claims that people nevertheless engage in local ruses and tactics "that are neither determined nor captured by the systems in which they develop." That is to say: local and individual practices do not fully yield to the system of power that for the most part controls them. Instead, they feature constant sleights of hand, bouts of opportunism, inventive trickery. De Certeau speaks of these tactics as constituting an art of powerless people, those who live under an alien god whom, in small ways, they can disable or circumvent.

I end with these few speculations. In the electronic age we are all powerless: power is in other hands. But we can still practice what de Certeau calls tactics, diversionary exercises, ruses. Perhaps these are what we should be teaching our students: tactics of evasion, the skill of detecting simulacra presented to us as real. We might teach our students the art of irony and train them to note discrepancies between one image and another, or between an image and its official discourse. In such an undertaking we might practice what Stanley Cavell calls "aversive thinking" following Emerson, who in "Self-Reliance says, "The virtue in most request is conformity. Self-reliance is its aversion."

Aversive thinking about the age of the TV screen proposes a critical relation to the world we live in and the instruments by which power is exerted. If we want a motto for this, apart from Emerson's phrase, I offer Kenneth Burke's account, in Counter-Statement and other books, of the aim of literature and criticism alike, aesthetically considered: to prevent a society from becoming too completely, too hopelessly, itself.