1

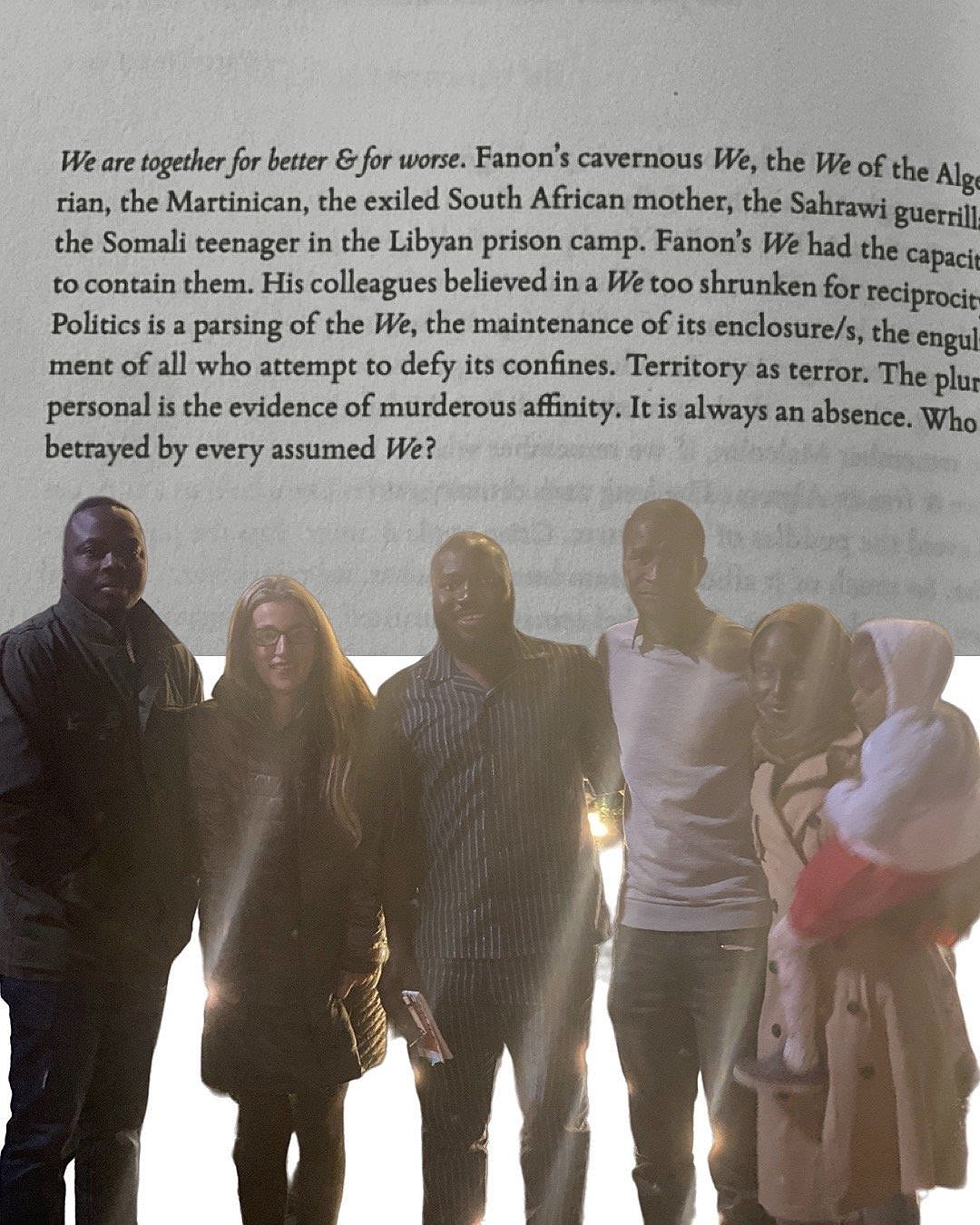

J.-A. Mbembé's "Necropolitcs" in the margins of images and repetitions. Mbembe quotes Fanon extensively when describing how necropower operates:

The town belonging to the colonized people . . . is a place of ill fame, peopled by men of evil repute. They are born there, it matters little where or how; they die there, it matters not where, nor how. It is a world without spaciousness; men live there on top of each other. The native town is a hungry town, starved of bread, of meat, of shoes, of coal, of light. The native town is a crouching village, a town on its knees.

2

Sovereignty began with the divine right of kings, in the relationship invoked by the elite to emphasize their privilege of access.

[“I am the one appointed to do God’s will. I am the recipient of the revelation. My body deciphers this will.”]

Loyalty to the sovereign demonstrates loyalty to God.

An imaginary with a Jade Emperor.

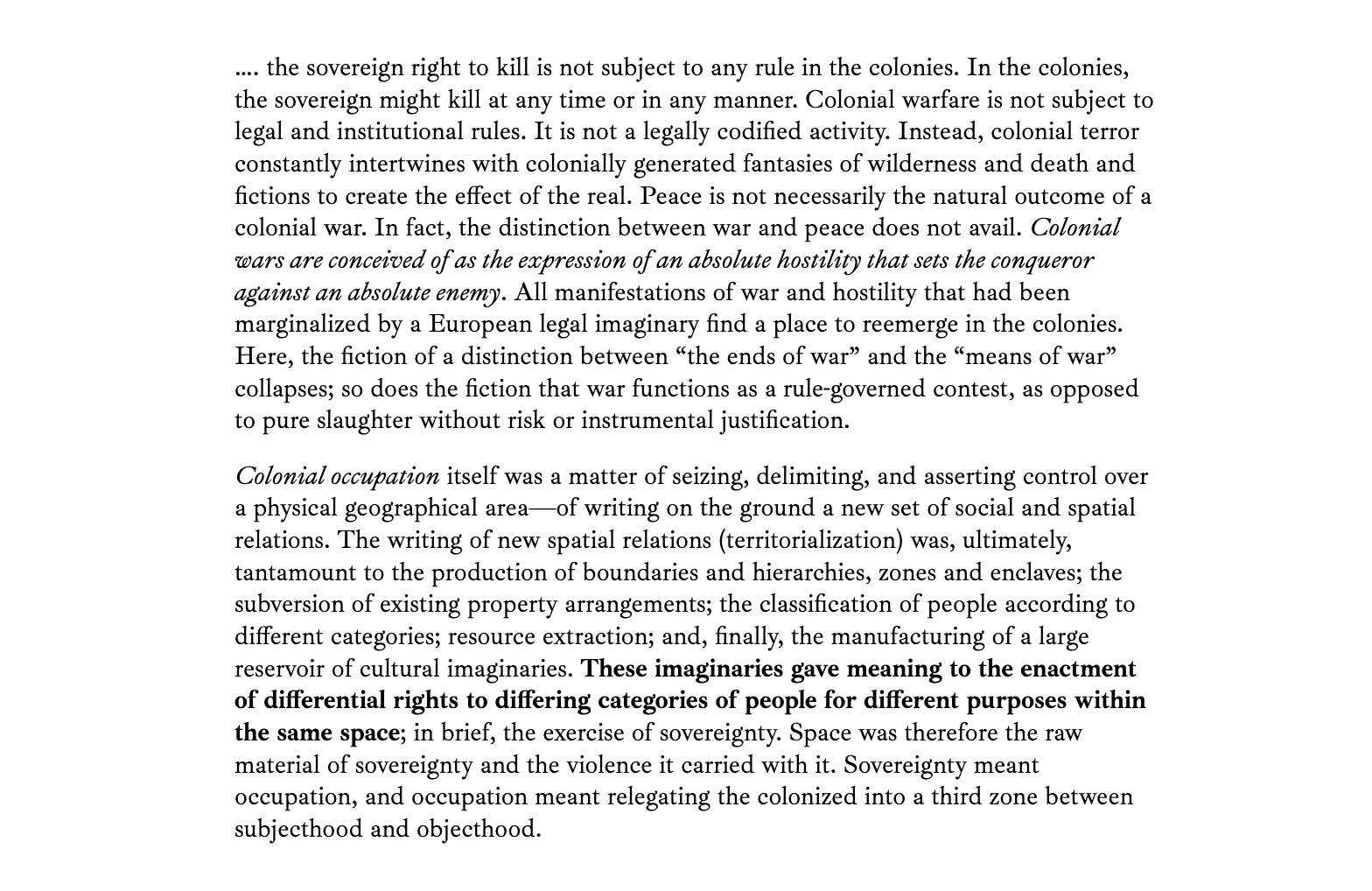

Mbembé' on the European legal imaginary:

Under the wikipedia section on names and forms of address for the Emperor of China, there is a subheading which reads: “To see naming conventions in detail, please refer to Chinese sovereign”

Beneath this subheading, one finds:

As the emperor had, by law, an absolute position not to be challenged by anyone else, his or her subjects were to show the utmost respect in his or her presence, whether in direct conversation or otherwise. When approaching the Imperial throne, one was expected to kowtow before the emperor. In a conversation with the emperor, it was considered a crime to compare oneself to the emperor in any way. It was taboo to refer to the emperor by his or her given name, even for the emperor's own mother, who instead was to use Huángdì (皇帝), or simply Ér (儿; 兒, "son", for male emperor). The given names of all the emperor's deceased male ancestors were forbidden from being written, and could be avoided (避諱) by using synonymous characters, homophonous characters, or simply leaving out the final stroke of the tabboo word. This linguistic feature can sometimes be used to date historical texts, by noting which words in parallel texts are altered.

Jacob Bryant, “Orphic Egg” (1774)

3

Any serious imaginary grounds itself in a physical claim that is tied to a cosmos. The territorial sanctifies the urge for conquest and ownership esoterically. Here is how wikipedia does cosmology:

Religious or mythological cosmology is a body of beliefs based on mythological, religious, and esoteric literature and traditions of creation and eschatology. Creation myths are found in most religions, and are typically split into five different classifications, based on a system created by Mircea Eliade and his colleague Charles Long.

Types of Creation Myths based on similar motifs:

Creation ex nihilo in which the creation is through the thought, word, dream or bodily secretions of a divine being.

Earth diver creation in which a diver, usually a bird or amphibian sent by a creator, plunges to the seabed through a primordial ocean to bring up sand or mud which develops into a terrestrial world.

Emergence myths in which progenitors pass through a series of worlds and metamorphoses until reaching the present world.

Creation by the dismemberment of a primordial being.

Creation by the splitting or ordering of a primordial unity such as the cracking of a cosmic egg or a bringing order from chaos.

The preferred cosmology of modern empires is the promise to bring order from chaos—- to tame and civilize; to make productive; to modernize and develop; to de-barbarize.

The preferred costume of 21st century empire is neoliberal democracy.

I mourn the decline of the orphic egg and the sexy, cave-dwelling oracle that refused to do the bidding of kings, empires, and state governments. My imaginary works this out in my own imagi-nation.

4

"In this case, sovereignty means the capacity to define who matters and who does not, who is disposable and who is not," Mbembe adds.

Late-modern colonial occupation differs in many ways from early-modern occupation, particularly in its combining of the disciplinary, the biopolitical, and the necropolitical. The most accomplished form of necropower is the contemporary colonial occupation of Palestine. Here, the colonial state derives its fundamental claim of sovereignty and legitimacy from the authority of its own particular narrative of history and identity. This narrative is itself underpinned by the idea that the state has a divine right to exist; the narrative competes with another for the same sacred space. Because the two narratives are incompatible and the two populations are inextricably intertwined, any demarcation of the territory on the basis of pure identity is quasi-impossible. Violence and sovereignty, in this case, claim a divine foundation: peoplehood itself is forged by the worship of one deity, and national identity is imagined as an identity against the Other, other deities.

History, geography, cartography, and archaeology are supposed to back these claims, thereby closely binding identity and topography. As a consequence, colonial violence and occupation are profoundly underwritten by the sacred terror of truth and exclusivity (mass expulsions, resettlement of “stateless” people in refugee camps, settlement of new colonies). Lying beneath the terror of the sacred is the constant excavation of missing bones; the permanent remembrance of a torn body hewn in a thousand pieces and never self-same; the limits, or better, the impossibility of representing for oneself an “original crime,” an unspeakable death: the terror of the Holocaust.

5

Mbembe appends the following foot-note to the paragraph quoted above:

See Lydia Flem, L’Art et la mémoire des camps: Représenter exterminer, ed. Jean-Luc Nancy (Paris: Seuil, 2001).

Thus does Jean-Luc Nancy enter the room through the sidereal. "I don't want to venture into the silence of the outside that surrounds the thing itself as soon as it emerges," Nancy wrote in The Fragile Skin of the World.

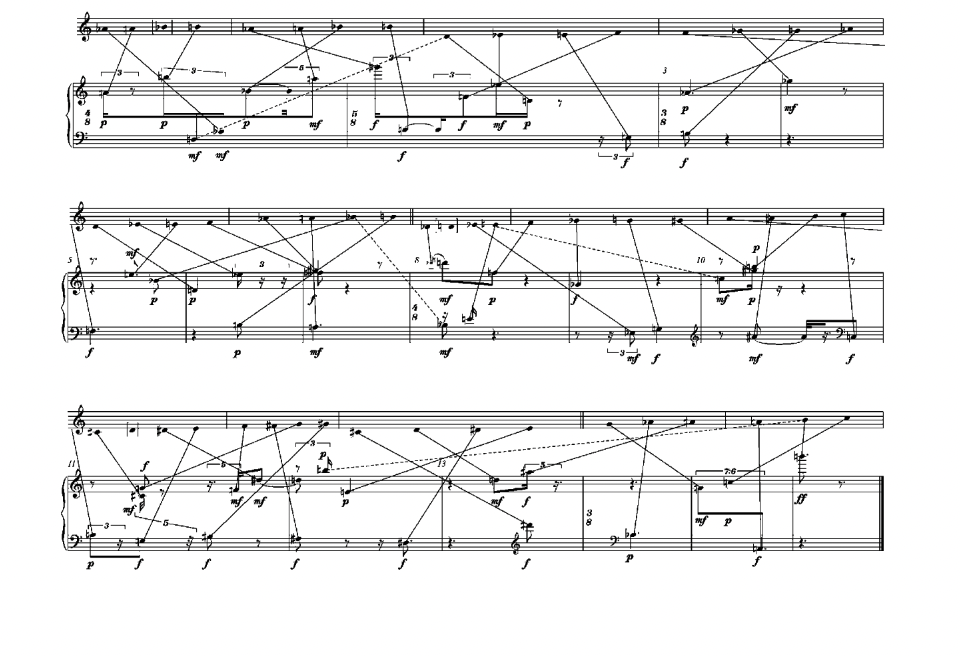

The book opens with an “Overture,” a formal gesture that draws on the symphonic mode to introduce his exploration of space-time's fragility, and how this fragility counterposes the possibility of an all-encompassing skin:

“We can no longer count on anything —- this is the situation.”

We can longer count our way through the exclusions of all the elsewheres.

As for the situation, it inscribes the I’s relationship to the site. The situational gaze is sited.

6

What gives the colonial government unlimited power over an occupied territory?

The state of siege is itself a military institution. It allows a modality of killing that does not distinguish between the external and the internal enemy. Entire populations are the target of the sovereign. The besieged villages and towns are sealed off and cut off from the world. Daily life is militarized. Freedom is given to local military commanders to use their discretion as to when and whom to shoot. Movement between the territorial cells requires formal permits. Local civil institutions are systematically destroyed. The besieged population is deprived of their means of income. Invisible killing is added to outright executions.

Even when rendered visible, “invisible killing” remains unseeable at present.

To see is to have a body that may be attached to a hand: to see is to see one’s hand in it.