This resistance mentioned by Belieu kept dragging Christina back into the frame as I read. Wyeth titled it after his model, Anna Christina Olson (1893 to 1968) who lived in Cushing, Maine on the farm pictured.

She had a degenerative muscular disorder that took away her ability to walk by the late 1920s. Eschewing a wheelchair, she crawled around the house and grounds. Wyeth, who had summered in Maine for many years, met the spinster Olson and her bachelor brother, Alvaro, in 1939. The three were introduced by Wyeth's future wife, Betsy James (b. c. 1922), another long-term summer resident. It's hard to say what fired the young artist's imagination more: the Olson siblings or their residence. Christina appears in several of the artist's paintings. [Source]

5

Two separate lines from Paula Meehan's poem, "Death of a Field":

The memory of the field is lost with the loss of its herbs

The magpies sound like flying castanets

Loss in its ecological sense—the articulation of things which disappear if the particular meadow disappears.

In ecology, endemism is "the ecological state of a species being unique to a defined geographic location, such as an island, nation, country or other defined zone, or habitat type". For example, Bermuda cedars were prominent in Bermuda before the 17th century. Settlers arrived. By the end of the century, the cedars were nearly extinct, wiped out by the shipbuilding industry and foreign parasites. The Bermuda cedar is endemic to Bermuda.

Kudzu originated in Japan, though it has grown characteristic of the southern US landscape. Indigenous species that are found elsewhere are not considered endemic to a place —- they can survive in alternate locations. Kudzu is indigenous to Japan though not endemic.

Americans benefit from "sweepstakes colonization,” living in a geographical location that has been largely spared the ravage of climate change. We have done nothing to deserve winning this lottery. We have neither tended nor protected this site of good fortune "rendered even more advantageous, as opposed to the "losing" species, which immediately fails to reproduce..." etc.

6

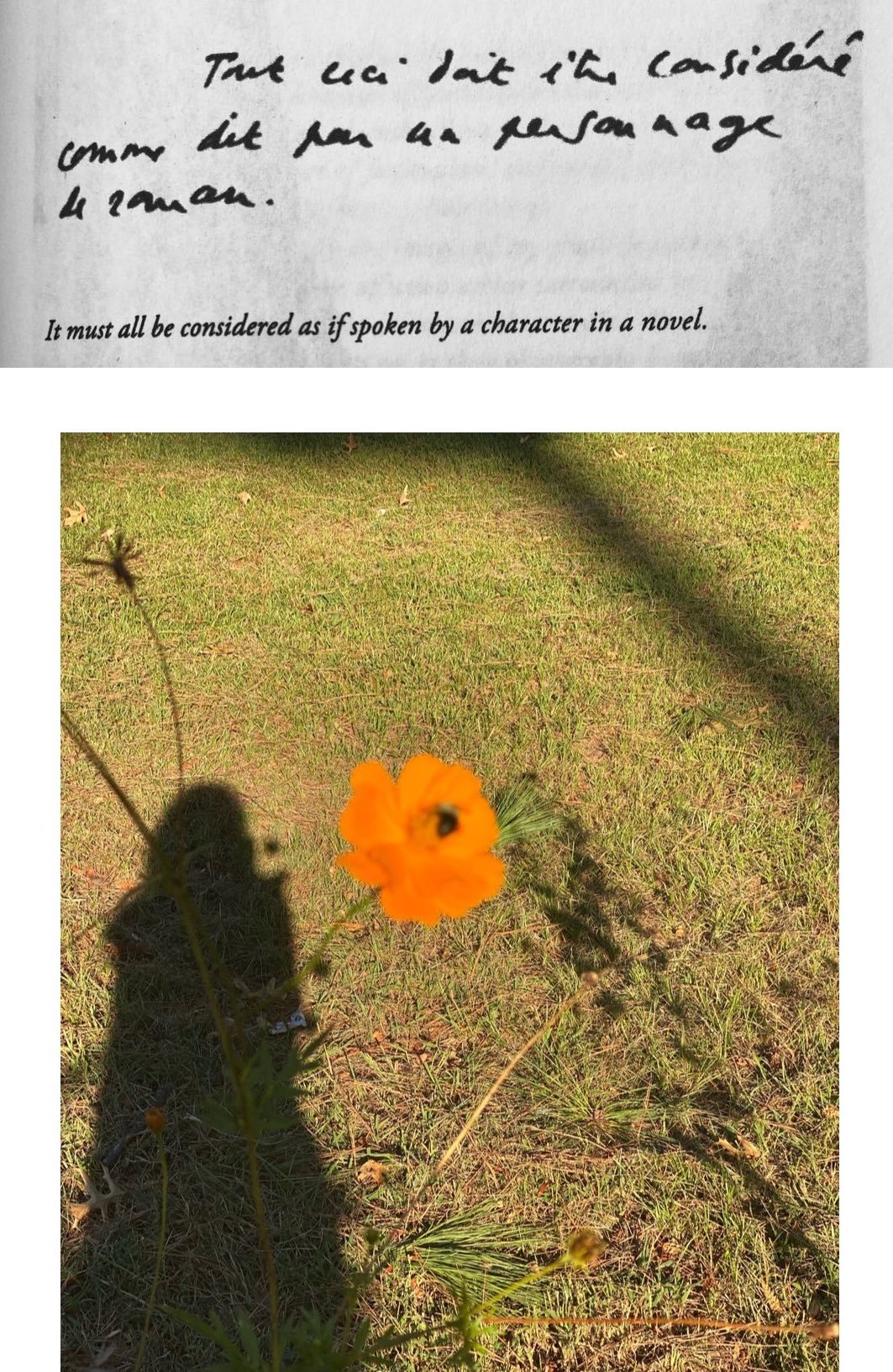

Joshua Marie Wilkinson said that we are drawn to what the photo or poem wants when we look at it. We are trying to learn how to want, and to desire – and how this occurs "is the poem’s secret to keep, and the photograph’s secret to flaunt.”

Here is the end of Rick Barot’s poem, "The Field”:

In the dark, alone, I went out to see the turn toward morning.

Then I saw them. What the imagination would do with two people

sleeping in a field is keep them where they are,

unknowable, untouched. The imagination also wants them

to stir, to wake them back into their stories.

The day will be hot. The smell of yesterday’s heat

is still in the air, like the sweat of a body. What would bring me

to a field in the night and have me sleep there?

Whose hand would I be holding, out of desire or fear?

My pants’ hems are heavy with dew. I know how far away

I am from everyone. Am I a child again, am I old?

Or am I only who I am now, astounded at the transport of the body

from one end of time to another.

- Rick Barot, "The Field"

What should the eye want of the mysterious couple's image? Barot tells us the imagination has a script to "wake them back into their stories." His brings his own story, his childhood fears, into this space with the couple. There are shadows between them, and those shadows are what the poet recognizes. These are the voices he brings to the page.

This poem exemplifies the first-person roving camera. I’m thinking of how Caryl Pagel urged writers to allow “the poem to be an exercise in haunting instead of starring, an act of investigation instead of performance”; and how, in such poems, the first person I doesn’t serve as as a signifier of self, but as a roving camera or seeing instrument. Desire lurks in the heart of this roving motion, and something here is the poem’s secret to keep.

7

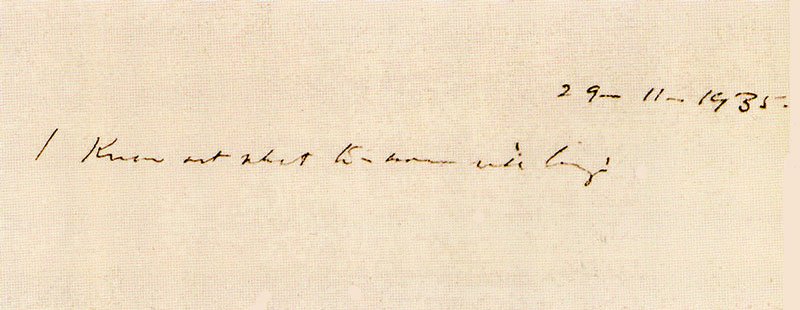

"All photographs are ambiguous," John Berger warns, "All photographs have been taken out of a continuity."

Dom Bury’s “The Opened Field” gives us a word in the title which frames how we read it: this field is opened, something happened to open it, and part of the poem’s journey will exist in relation to this word.

Three boys stand in a frozen field —

each child stripped and hosed, the next task

not to read the wind but learn the names

we have for snow, each name

we have given to the world. To then unlearn

ourselves, the self, this is — the hardest task.

To have nothing left. No thing but heat to give.

- Dom Bury, "The Opened Field"

"Ruins are a way of seeing," Robert Harbison wrote. It feels as if one is looking at the ruins of field rather than its destruction—at the ruins of the children in relation to the field. The frozen position of statues.

8

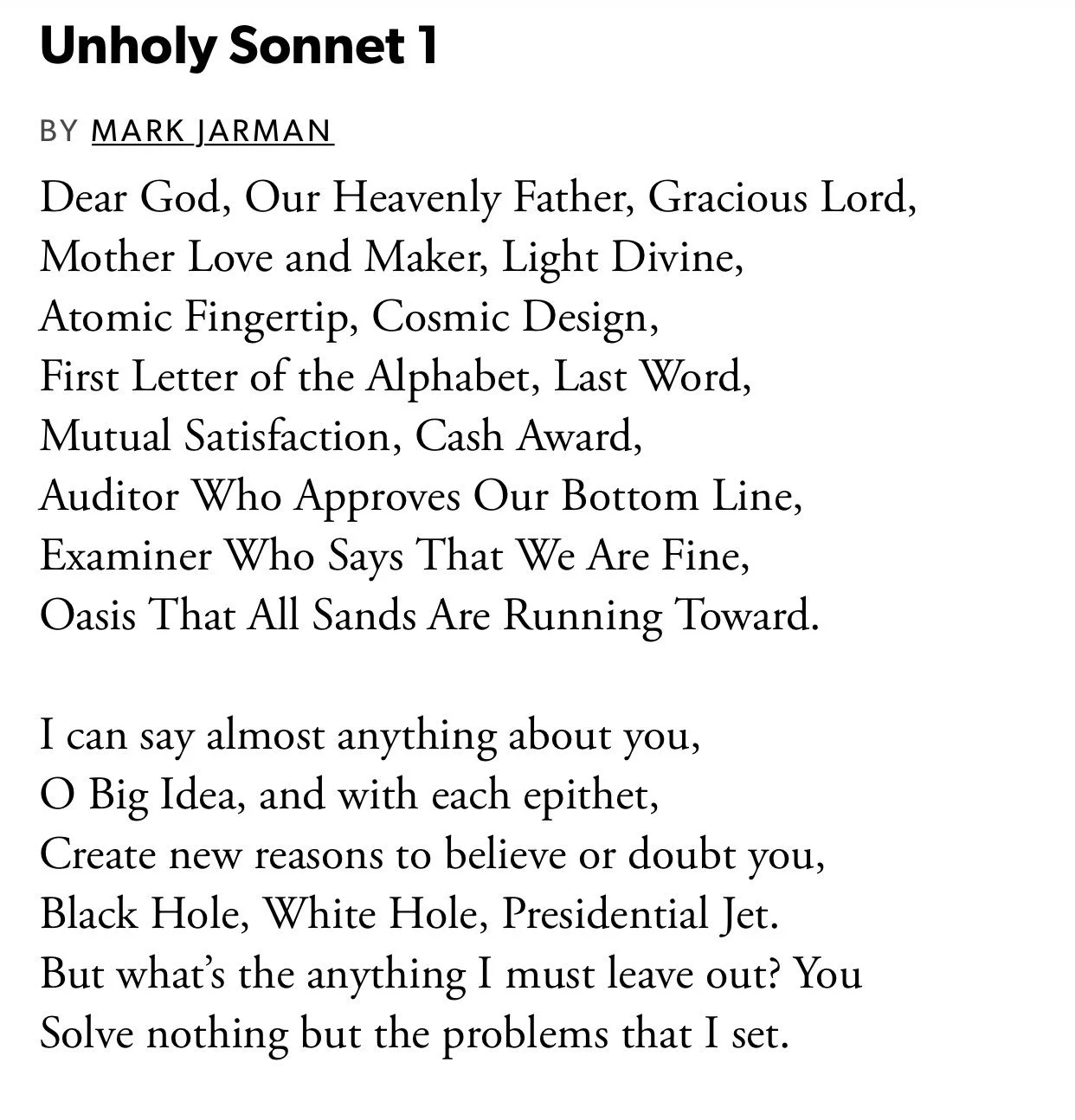

Leslie Scalapino called the assembling and arranging of photographs "a kind of contemplation." Louise Gluck’s formidable You is deeply contemplative and meditative. She often uses flowers as icons to focus concentration, and addresses them as one would address a divinity or a beloved.

What are you saying? That you want

eternal life? Are your thoughts really

as compelling as all that? Certainly

you don’t look at us, don’t listen to us,

- Louise Gluck, "Field Flowers"

I’m also thinking of how Dolores Dorantes' untranslated dictionary images in COPY (Wave Books) resemble small scenes in a film without subtitles – one wants to read the gesture in order to recover them from the narrative. But there are iconic in the sense that they encourage meditation rather than analysis—- to think upon a thing rather than to think through it. Poetry allows us to treat images as meditative icons, and to complicate this through invocative address.

9

In "Two Versions of the Imaginary," Maurice Blanchot describes the image as that which is present in its absence, or something which appears as a disappearance.

Remind me to show you where the horses finally got freed

for good—not for the freedom of it, or anything like

beauty, though their running was for sure a loveliness, I'm

thinking more how there's a kind of violence to re-entering

unexpectedly a space we never meant to leave but got

torn away from so long ago it's more than half forgotten

- Carl Phillips, "Pale Colors in a Tall Field"

I think of these of two versions of the imaginary in Carl Phillips’ poem, with its lush, long lines and careful enjambments, and the echolocutive effect of these enjambments which echo back and forth across the field and the mind recovering memory in moments, fragments, snatches. To re-stage the moment which touched us is tremendous.

10

Here is the entirety of a poem which looks at a field, or makes use of the images evoked by a field.

"The Bright Field" by R. S. Thomas

I have seen the sun break through

to illuminate a small field

for a while, and gone my way

and forgotten it. But that was the

pearl of great price, the one field that had

treasure in it. I realise now

that I must give all that I have

to possess it. Life is not hurrying

on to a receding future, nor hankering after

an imagined past. It is the turning

aside like Moses to the miracle

of the lit bush, to a brightness

that seemed as transitory as your youth

once, but is the eternity that awaits you.

The relationship between normalizing and making something seem inevitable is the strategy of religious fundamentalists who refuse action on climate change. They believe the end of the world is God's will. To contest God's will is to be unfaithful, or disloyal. Life is not hurrying . . . It is the turning.

11

“Poetry is always the cat concert under the window of the room in which the official version of reality is being written," poet Charles Simic wrote in "The Flute Player in the Pit.” In the same essay, Simic links the desire of the image to that of the poem: “The secret wish of poetry is to stop time….. Poems are other people’s snapshots in which we recognize ourselves.”

“Scientifically Speaking” by David Tomas Martinez

There have

been exciting

discoveries

in the field

of me.

Many

of which

I have

made

myself.

In this poem from Hustle (Sarabande Books, 2014), David Tomas Martinez uses words associated with science (discoveries, field of) and applies them to himself. There have been exciting discoveries in the field of me. I love this line for its simplicity, and for the surprise of the final clause— “of me”—which carves the self as a field worthy of attention.

Martinez makes use of a narrowed margin which foregrounds understatement, and results in a sort of mysterious humility—the speaker doesn’t inventory his findings or list his scientific observations. Instead, he overturns the concept of discovering as used in headlines about the latest scientific etc.

To quote Simic again: Poems are other people’s snapshots in which we recognize ourselves. Recognizing often has the thrill of discovery, and Martinez’ discover of “the field of me” has the shape of a permission to other poets to recognize ourselves in the relationship between the poetic field (i.e. it’s projections, it’s use of space, it’s lineation) and ourselves.